Ania Szremski

Ania Szremski

Dreadful rooms, dreadful colors, dreadful love: in Rosemary Tonks’s 1972 novel, a woman on the verge is desperate for a way out.

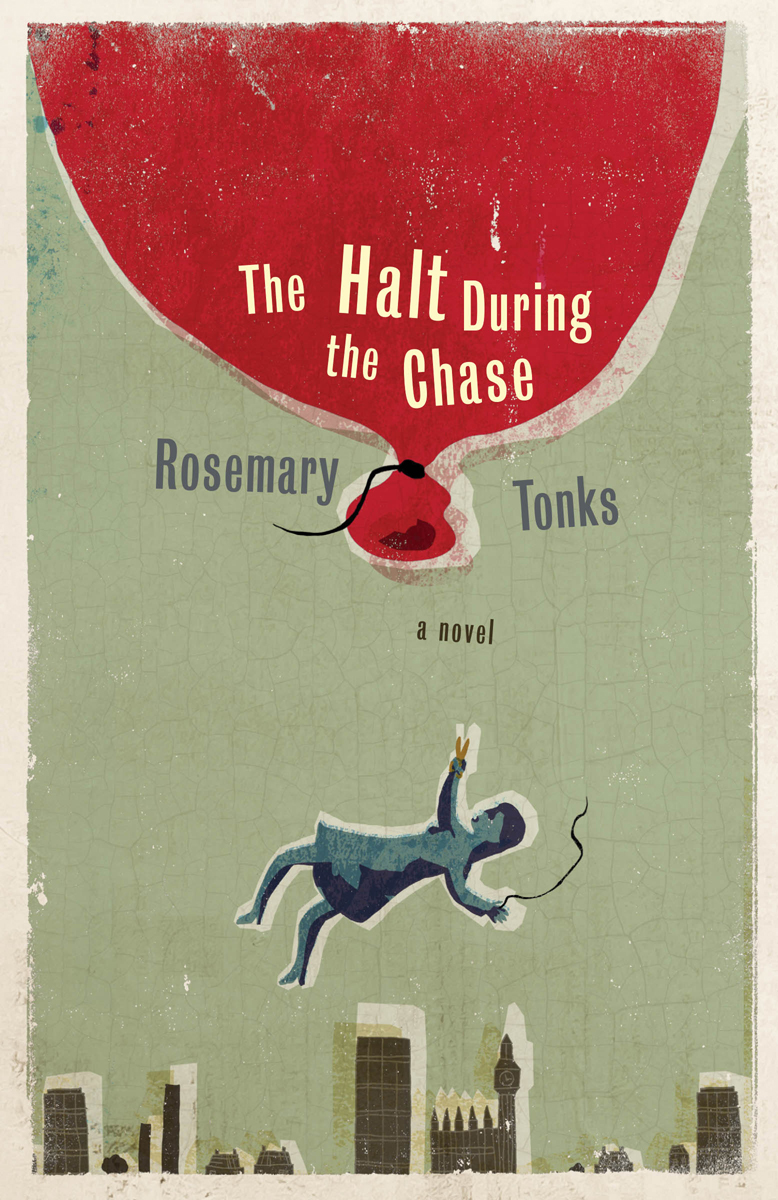

The Halt during the Chase, by Rosemary Tonks,

New Directions, 218 pages, $17.95

• • •

English author Rosemary Tonks’s compact 1972 novel The Halt during the Chase—the third recent reissue of her long-inaccessible work—is a love story that’s not really about love at all, in love’s truest sense. It’s a study in certain ways of relating that are socially given as love—the suffocating, correlative conspiracy between a mother and daughter; the cringingly lopsided shape of a woman’s infatuation with a man who lazily dangles the possibility of reciprocation. The cascade of effects this loving causes—a loss of self, a strangling anger of wanting, a proclivity for causing scenes, hyperventilation—begs a feminist modality. Is it possible for a woman to submit to such common formats of love, Tonks seems to ask, without ending up throttled, gasping for air?

Between the ages of thirty-five and forty-five, Tonks produced two volumes of poetry, essays on authors including Colette and Adrienne Rich, and six novels, all critically acclaimed in her lifetime. Each of the novels centers on a young(ish) woman at a crossroads, vexed by love or the chance of it. Tonks, after dropping out of school as a teenager, had married at age twenty, abandoning the London literary circles she had precociously begun exploring to follow her husband around the world for his work. Along the way, Tonks contracted paratyphoid and polio, which blinded her for a year and destroyed her right hand. She learned to write with her left and resumed her literary pursuits when they resettled in London. By the time she drafted The Halt during the Chase, her last published novel, her husband had left her. Given how her stories are mingled with autobiographical elements, one might wonder if Tonks was compulsively zeroing in on an imagined version of herself, a woman on the precipice of fatal entrapment but who still has her options open, could still spin on her heel and go the other way.

This final assay may be the most effective distillation of that preoccupying formula. The avatar here is Sophie, thirty-one, working middle-class, unmarried and desperately pining for the handsome, wealthy, hypocritically Socialist, very correct Philip—her childhood friend and casual lover. She has just quit her job at the Languages School so she may dedicate herself to being “available to see him during the day, and to get my flat done up, so as to make it more attractive to him, and to have time to improve my own appearance. I knew I had to keep up a certain style in order to attract Philip. He hated anything that wasn’t quite right. But then, nothing ever is.”

Love, in Sophie’s world, is sleight of hand, spangled musical comedy, “underworld theatre.” Her mother, unable to afford real make-up, had “bagged” her husband by rubbing powdered chalk on her face, like a mime (she “got herself loved,” Sophie explains, “by bamboozling whoever it was, and not giving up”). Sophie applies ridiculously obvious false eyelashes that Philip compliments, to her embarrassment, at a dinner where they eat and drink “like two silly marionettes in a vaudeville act entitled ‘At Dinner.’ ” Filial love is just as staged. Sophie’s consciousness may tremble with thoughts of Philip, but the deeper love story is with her mother, who had raised Sophie alone, her father having died when she was a baby (just like Tonks, whose own mother had unexpectedly passed away a few years before she wrote this book). Sophie has lost out on having a childhood, having been “apportioned . . . the role of basket-carrying husband, moral leader and decision-taker,” consumed with filling her mother’s monstrous need by performing excessive acts of devotion, bound in a mutually flirtatious dependence that in adulthood she still can’t escape, even by lobbing emotional grenades.

The book opens with mother and daughter volleying competing memories over the implacable barricade of an ironing board, deliberately wounding each other, with pleasure, and immediately making up, out of guilt and desire, until they dissolve into laughter so hysterical it hurts their stomachs. Laughter functions to break the fourth wall, slice it open onto the reality that Sophie, so tired of playacting, longs for. Sophie never laughs with Philip, who prizes seriousness, who punishes her for having a sense of humor. That she laughs so truly with her mother is a sign that their love, on the other hand, may be redeemed.

This is an exaggeratedly domestic novel, whose action unfolds in rooms gorged with furniture and objects, all brimming with meaning. Sophie knows how her mother is feeling based on the pitch of her iron’s hiss; clocks are always ticking or being wound when Philip is near or on the mind—he himself “had a clock buried in his flesh.” These objects, furnishings, and many, many articles of clothing are described with tender care and in vivid color. The Halt during the Chase shares its title with one of Watteau’s last paintings, a picture plane of variegated greens and foresty browns whirling around a shock of canary yellow, just off-center: the velvety gown worn by a fair maiden trying to dismount her horse, gingerly lowering herself into the arms of an eager male attendant. It’s a lovely coincidence (or is it?) that these are the exact colors of significance in Tonks’s text, also filled with greens and browns that set off a visual fulcrum of the same hue: a lurid “urine-yellow” sofa that provokes revulsion and covetous feelings at once (Sophie suspects this may have been the site of Philip’s conception).

There is comfort, safety, familiarity in all this ticking and stuffing, but there is also the precipitous danger of a lethal smothering. In a dreadful, surfeited hotel room Sophie shares with Philip one fateful night, he casually mentions the expiration date he foresees for their relationship, and she reels with claustrophobia. She feels she herself will expire in this overheated, oxygen-deprived room, whose window she can’t get open, a window that looks onto a vertiginous forty-foot drop. The dark plunge, the wet and muck of nature, the profound quiet of a winter night—this is the intoxicating foil to the stifling interior world of Sophie’s drama of love; an exhilarating, feral alternative. When Sophie, determined to get over Philip, heads to a family acquaintance’s decrepit château in Normandy, she finds strength in this much emptier, chillier architecture, where icy wind whips through the halls and the clocks are unwound, where she can sit in unmeasured silence. She remembers that when she was little, playing outside in the wild grass, she had had a remarkable “ability to vanish.”

Tonks may be more famous for her own vanishing act than for her writing (after all, what’s more compelling than a woman who doesn’t want to be seen?). Her conversion to Christian extremism, repudiation of her work (she burned copies of her books and denied republication requests), and withdrawal from public life until her death, at age eighty-five, in 2014, is often interpreted as tragic, but perhaps it could be seen another way—maybe a different, more agential vision could be presaged in this last novel. The custodian of that offensively yellow couch is Sophie’s dear older friend, the impossibly glamorous Princess Melika, who “had extricated herself, first from Russia, and then from Paris, and it was during that lifetime’s journey that she had learnt to live for herself.” Maybe she is the woman Tonks aspired to become—the one who dares to unfasten restricting binds, even of love, in order to live for herself. Melika opens the door for Sophie to do the same. “Do you want a life or don’t you?” she asks the younger woman. “I do,” Sophie answers. “Well, hurry up.”

Ania Szremski is the senior editor of 4Columns. She is writing a novel about love.