Kaelen Wilson-Goldie

Kaelen Wilson-Goldie

Soraya Antonius’s 1986 novel, newly reissued, paints a breathtakingly vivid portrait of pre-nakba Palestine.

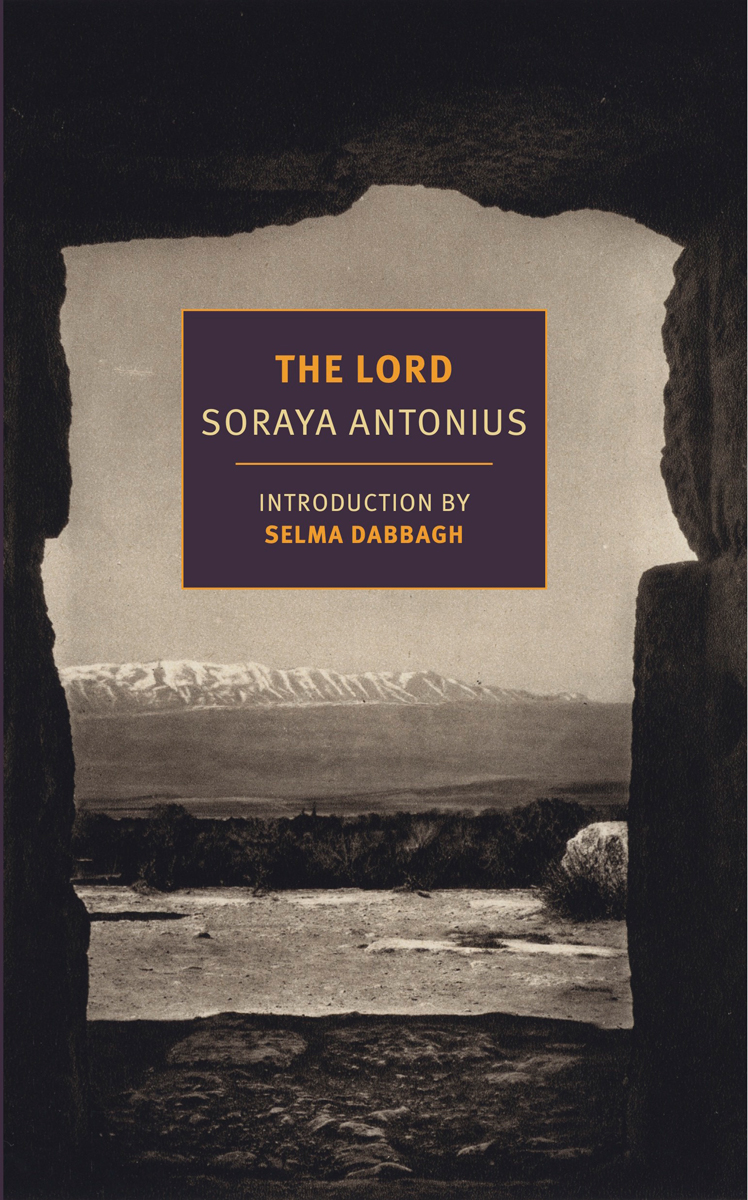

The Lord, by Soraya Antonius,

New York Review Books, 227 pages, $17.95

• • •

Soraya Antonius’s novel The Lord begins and ends among the ruins of a Crusader castle. To get there, a world-weary journalist, never named, has traveled through a rolling green landscape, a place where “the contiguous hills and coasts of Lebanon and Palestine merged indistinguishably,” only to find the ruins are fully inhabited by a sprawling village. The journalist is sitting in the passenger seat of a car driven by her partner, Nicholas. He is furious because she has already picked up a tortoise and a trunkful of plant cuttings along the way. A small boy is shouting outside her window, feigning to sell her a half-dead bird, presumably a pigeon, tied up with string. “Buy it,” he cries, “and you can untie the string and let it go free.” The journalist hands over two lira and grabs the bird just as Nicholas floors the accelerator. The bird survives and turns out to be a baby hawk. That’s the start of Antonius’s frame story, which is riveting and cinematic and heavy with symbolism. I won’t tell you how it ends, when the couple return to the ruins and set the bird free, but it is brutal and shocking and above all true to the story told in between.

At the core of The Lord, first published in 1986 and newly reissued by NYRB Classics after falling out of print, is a young man named Tareq in Mandate Palestine. His story is pieced together for the journalist by various interlocutors some five decades after his death. The action shifts constantly, moving back and forth from the 1980s to the 1930s, with scattered intimations of the 1960s and the turn of the twentieth century. The journalist interviews Egerton, a British reporter sympathetic to the Palestinian struggle, but the bulk of the novel concerns the recollections of Alice Rhodes, a former teacher whose father established an Anglican missionary school in Jaffa. Tareq was one of her students. His performance was so lackluster that when he aced his final exams, the school board denounced him for cheating. But Alice intuited something was going on. In flashback, she wonders: Is he smart, gifted, actually a genius? “It’s hard to explain,” he tells her. “Let me show you something.” He points to a poorly moored dinghy. In an instant, the boat vanishes and reappears, neatly secured. He tells her that voices speak to him from beyond the stars.

From there, Tareq traverses Mandate Palestine. He moves from village to village, performing acts of magic ranging from standard-issue sleights of hand to the seemingly supernatural. He walks through walls, turns a flask of forbidden brandy into an allowable drink of mulberry juice, and transforms drab British bowler hats into resplendent keffiyehs. He reverses a curse on a woman’s childbearing abilities. And then, the body of a British functionary suddenly flashes naked before a flabbergasted crowd. All in attendance are stunned into silence but immediately doubt what they have seen. So did he or didn’t he? Is Tareq really a magician? Does he have special powers? Is he some kind of a prophet, a miracle-worker? The British administration begins to suspect Tareq is in fact the mastermind behind the real historical events of the 1936–39 Arab Revolt, which began in Jaffa and tried to win Palestinian independence by defeating the mandate—a decade before the creation of the state of Israel.

Antonius, who died in 2017 at eighty-five, was a journalist and critic who spent most of her adult life in Beirut. She wrote for the French-language newspaper L’Orient, the covertly CIA-funded magazine Hiwar, and the Journal for Palestine Studies. In 1965, she published a slim but powerful book about vernacular Lebanese architecture, winding pithy descriptions and a preservationist spirit through a raft of phenomenal black-and-white photographs, archival and contemporary (accordingly, the best passages in The Lord are those recreating the architecture and agriculture in pre-nakba Palestine). Antonius wrote just two novels—The Lord and its sequel, Where the Djinn Consult, published in 1987—both of them drafted quickly and ferociously in the aftermath of the Israeli invasion of Lebanon and the Sabra and Shatila massacres of 1982.

The more pertinent biographical details, however, concern Antonius’s family. She was the only daughter of the writer and diplomat George Antonius—the Cambridge-educated author of The Arab Awakening, the ur-text of Arab nationalism, published in 1938—and the socialite Katy Nimr. Wealthy, cosmopolitan, and multilingual, Antonius and Nimr had roots all over the Levantine world. As a matter of choice both rare and highly privileged in this region, they self-consciously made Jerusalem their home and Palestine their homeland. Soraya was born and raised there. But after surviving two traumatic events in quick succession—her cousin was killed when he picked up an unexploded ordnance and the King David Hotel was blown to bits while she was waiting outside for her mother—she was packed off to boarding school, first in Alexandria, then London. She eventually studied art at the Slade, under the influence of her maternal aunt, the surrealist painter Amy Nimr, one of the most talented members of the group Art et Liberté. And in 1951, Antonius met the Palestinian novelist Jabra Ibrahim Jabra, newly returned to Jerusalem from Baghdad, who convinced her to write—no matter the language.

Language, after all, was an issue. Like her father, Antonius wrote in English. The Lord’s savage critique of British imperialism is therefore aimed directly at the thing itself. Her villain, Challis—the British military chief who sets out to destroy Tareq—is sinister, fearsome, and outrageously detestable in any dialect. But Antonius walked a wiggly linguistic line. Even though she could certainly speak Arabic, she once explained that, in fiction, “even if I couldn’t write in Arabic, I could still write as an Arab.” This echoes the work of Etel Adnan, who often argued that she wrote in English (and French) but painted in Arabic. The Lord belongs on the same level of excellence as Adnan’s 1978 novel Sitt Marie Rose. Cluster them together with other works in literature and cinema that are set, for similar reasons and to equal effects, in Mandate Palestine—Isabella Hammad’s The Parisian (2019), whose unforgettable protagonist is similarly rattled by curses; Jumana Manna’s short film A Sketch of Manners (2013); Heiny Srour’s feature Leila and the Wolves (1984)—and you’d have a feminist tour de force capable of offering a few clues for exiting the mayhem and horror of the region now.

What does it mean to write in one language as if in another? A similar question: What does it mean to read in the present as if in the past? The Lord tunnels into the lost worlds of Palestine before Israel, not as counterfactual or nostalgia. It rebuilds those worlds as text, through breathtaking descriptions. “The city sloped away below them in serrated gradations of duns, pale ochres and gazelle-skin rectangles with vaulted domes faintly shadowed by the afternoon sun . . . The stone-flagged terraces curved with age . . . spilling with jasmine and basil and rosemary, tight-furled little roses, so dark a red as to be blue.” The plot of The Lord captures the highs and lows of human stupidity. Antonius’s characters are as hopeless as they are familiar to today’s readers. But her settings do something more. They root into the soil. They expose ancient forms of coexistence. They reclaim the possibility of beauty, translatable in all directions.

Kaelen Wilson-Goldie is a writer and critic based in Geneva.