Kaelen Wilson-Goldie

Kaelen Wilson-Goldie

A dazzling collection of poetry showcases the Egyptian writer Iman Mersal’s penchant for wondrous wisdom and ever-shifting interiority.

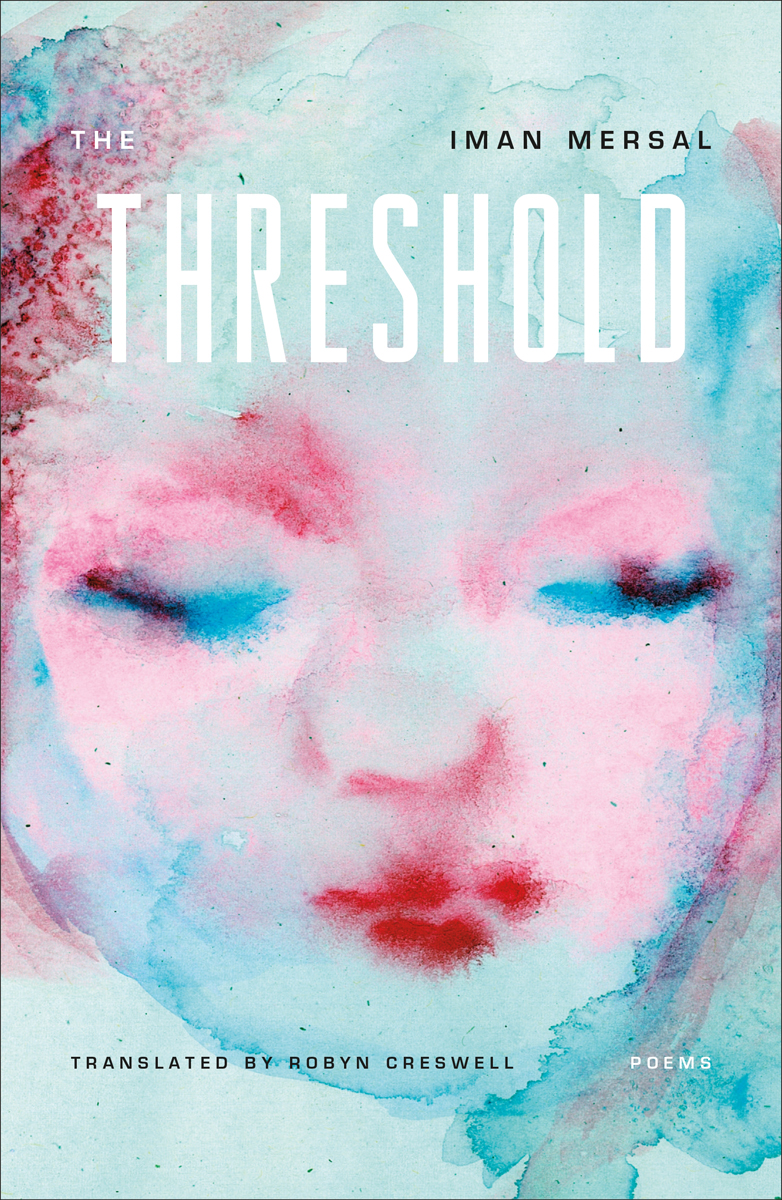

The Threshold, by Iman Mersal, translated by Robyn Creswell,

Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 107 pages, $13.99

• • •

The Egyptian author Iman Mersal writes poetry and prose. As far as defining a practice, the division seems absolute: creativity, questions of form, and figures of speech on one side; facts, expositions, and lines of inquiry on the other. On the one hand, Mersal’s poems address everyday details and fragments of memory. She lingers on fathers and dubious friends, many former lovers, women and weather, hospital beds and city buses and hidden cafes. Her emotional tenor is stormy but temperate. She tells of embarrassment, envy, and regret. She fans out a full spectrum of delicate expressions for curiosity, ironic detachment, and doubt. Irruptions of the surreal and absurd occur, but they don’t break the world apart. The characters in her strongest and most captivating poem, “The Threshold,” also the title of her ravishing new collection, tumble out of a theater and into the streets and, hours later, read a letter in a bar from a friend in Paris who admits to dragging his misery “over sidewalks much softer than Third World sidewalks / and going to pieces rather comfortably.” Mersal’s poems read like short stories; they are spare but resonant, full of charming misfits, and governed by chance.

Her powerful book-length essays, on the other hand, take on major political and cultural dramas. In recent works, Mersal has delved into the blame game of motherhood, a young writer’s suicide, and the still-shocking details of Saddam Hussein’s 1979 “Massacre of the Comrades” in Iraq. Yet the clarity of the line separating poetry from prose quickly dissolves into something else. Mersal writes herself into all her expository work, whether recreating her own diaries of early motherhood or admitting the extent of her distraction, sitting under the neon lights of some cold, fruitless library, dust burning the insides of her nose. To read through the loosely chronological sequence of forty-two poems featured in The Threshold, translated by the scholar and critic Robyn Creswell, with the titular poem as its centerpiece, is to experience the playful and serious mischief of how Mersal blurs, muddies, and obliterates the boundaries between imagination and argument, fiction and nonfiction, bracing formalism and layers of context.

Since 1995, Mersal has published four collections of poetry in Arabic, working almost exclusively with Cairo’s Dar al-Sharqiyat, a publishing house founded in 1991 and notably independent vis-à-vis the Egyptian state. Sharqiyat is known for its Arabic translations of everyone from Jorge Luis Borges to Annie Ernaux and for its hand in shaping the story of the “nineties generation” of Egyptian writers, including, among others, Mersal and the novelist Miral al-Tahawy. The nineties generation were said to have equaled the avant-garde of their outsize predecessors—writers such as Sonallah Ibrahim and Edwar al-Kharrat of the “sixties generation”—but turned their backs on the explicit positions of politically engaged literature, opting instead for coded language and interiority.

The Threshold draws from all of Mersal’s existing collections and features new translations of some seventeen poems previously published in These are not oranges, my love, translated by the poet Khaled Mattawa in 2008 (difficult to find if not definitively out of print). In Arabic, Mersal writes in a form known as qasidat al-nathr (“prose poem”), which only emerged in the 1950s. As Creswell notes in his agile introduction, qasidat al-nathr revolutionized Arabic poetry, which had functioned for more than a thousand years according to strict rules of meter and line length. Some of Mersal’s poems have line breaks, others do not. (Creswell’s translations are true to their original form.)

“CV,” for example, about whittling a life full of risk-taking and glorious failure down to a tidy, bloodless list of achievements, steps down the page, line by short line, like a Slinky expertly set in motion on a set of stairs:

A ruthless catalog of sorrows:

years in front of the screen, diplomas before jobs,

and languages—all that torture—now ranged under Languages.

Where are all the wasted days? And the nights

of walking with hands stretched out

and the visions that crept over the walls?

“Sound Counsel for Girls and Boys Over Forty,” meanwhile, proceeds in robust, wondrous paragraphs and ends with this morsel of wisdom:

As for the poetess who claimed that after forty she entered the stage of the butterfly, I beg you not to understand her in the way of those who say do not pray while forgetting to cite the words that follow in the Quran (while drunk). For in the very next line the poetess says she flew at lightning speed along the straight and narrow path heading toward the light—the very light that prophets and wise women call, in their metaphorical fashion, death.

The pacing of The Threshold moves generally from shorter, more fragmentary poems, such as the fourteen snapshot-like sections on illness that make up the series “The Clot,” to longer, more complicated pieces, such as “The Curse of Small Creatures,” about Mersal’s hometown of Mit ‘Adlan, in the Nile Delta (where she was born in 1966), and “An Essay on Children’s Games,” on the entanglements of exile and guilt (Mersal left Egypt in 1998 and now lives in western Canada). But Mersal constantly shifts back and forth. All her verse is characterized by pivots, where a line suddenly turns on a word, image, or passage, then plunges deeper into her subject. This happens most dazzlingly in the eponymous poem. The late-night adventures of the young people in the bar mentioned earlier expand to include a lifetime, an epoch, until, from a moment’s pause to reflect on the purpose of public toilets, “one long-serving intellectual screamed at his friend / When I’m taking about democracy / you shut the hell up / so we ran for it / until we could catch our breath on al-Mu‘izz Street.” Line breaks call visual attention to the accelerations and cinematic rhythms of Mersal’s verse, but the same turns and pivots animate her essays.

One might dare to imagine an anthology combining the poems with all the other kinds of writing. But the benefit of approaching Mersal as a poet, first, is to place her within the wider field of Arabic poetry. Creswell’s introduction dwells less on the differences between the sixties and nineties generations in Egypt, ultimately a provincial parlor game, and more on the differences between older poets such as Mahmoud Darwish, Adonis, and Nizar Qabbani, all men and all public intellectuals marked by the staggering Arab defeat in the Six-Day War of 1967, and a younger writer like Mersal, whose more pertinent—and complicated—lineage is Arab feminism rather than Arab nationalism. Creswell describes Mersal, provocatively, as an outsider poet. He notes her time as a founder of the feminist magazine Bint al-Ard (Daughter of the Earth), which she edited from 1986 through 1992, and offers crucial background to her poem “Amina,” about Mersal’s brief stay in a Baghdad hotel with her mentor Amina Rachid, part of a campaign by Egyptian feminists in solidarity with the Iraqi people, and an experience that opened a rift between aristocrats and outsiders on the political left. But like the cracks in the wall in “The Idea of home,” Mersal’s last, illuminating poem in The Threshold, which “keep growing until one day you take them for doors,” borders between different modes of writing, like rifts between feminists, have widened to create surprisingly generous and generative spaces. In Mersal’s oeuvre, they’ve opened a liminal zone the size of a small world, capacious enough for all her work, and the enthusiasm of her readers, to fit.

Kaelen Wilson-Goldie is a writer and critic who divides her time between Beirut and New York. A regular contributor to Artforum, Afterall, and Aperture, she is the author of two books: Etel Adnan (2018), on the paintings of the Lebanese-American poet Etel Adnan, and Beautiful, Gruesome, and True: Artists at Work in the Face of War (2022), about the multidisciplinary works of Amar Kanwar, Teresa Margolles, and the anonymous members of the filmmaking group Abounaddara.