Robert Jackson Wood

Robert Jackson Wood

Organs music: David Lang and Mark Dion put an operatic spin on public dissection.

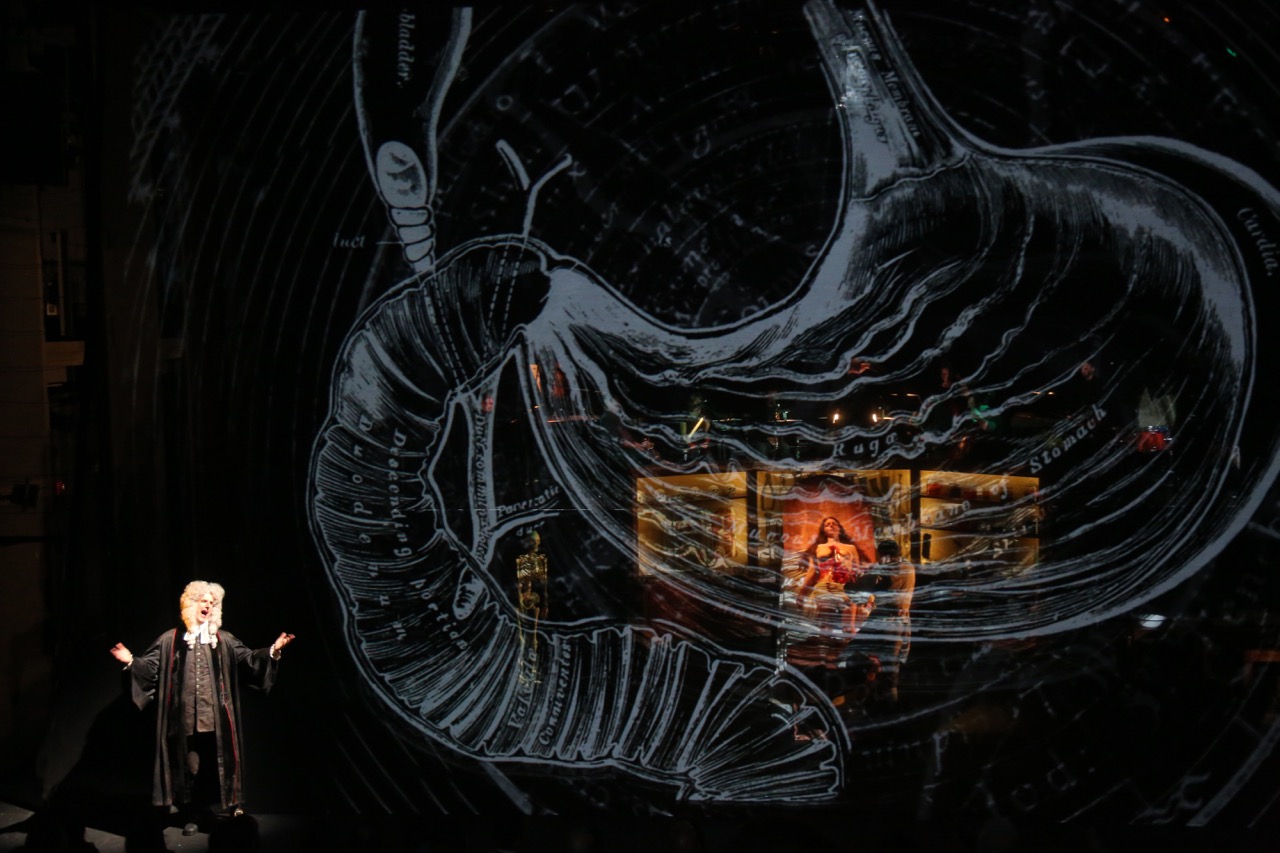

anatomy theater at BRIC. Photo: Craig T. Matthew.

anatomy theater, by David Lang and Mark Dion, BRIC, 647 Fulton Street, Brooklyn, New York, January 7–14, 2017

• • •

Common is the actor who bares her soul on stage. So how nice it is when one of them instead bares her spleen.

Or has it bared for her, in any case. At BRIC Arts Center on January 8, the actor was dead, fresh from the noose as the executed antihero of composer David Lang and visual artist Mark Dion’s gruesome musical-theater work anatomy theater, which had its New York premiere as part of the Prototype Festival. The subject was the grisly world of eighteenth-century public dissections, and, in this telling, blood and guts were hardly the most unsettling spectacle.

The history isn’t pretty. Until the early nineteenth century, it wasn’t unusual for physicians to pick apart the bodies of executed criminals in front of a morbidly curious male rabble. The rationalization was objective science, yet the truer goal was social control and punitive justice. The possibility of being publicly disemboweled helped to deter would-be criminals from future mischief. It also tried to put an objective measure on criminality itself; prove that a murderer’s heart weighed less than an Average Joe’s, and evil became much easier to understand. Otherness became quantifiable.

Lang’s program notes promised a macabre re-creation, not a distanced critical assessment, of one of these bygone carnivals of sanctimony, presumably assuming that modern-day audiences needn’t be told why we no longer, say, smell someone’s dissected stomach to better understand moral turpitude (yes, that happened). But progress has its blind spots. When a modern-day production is written by a man and most of the characters are men, and when the stomach under consideration belongs to a sexually abused woman, publicly humiliated and lying naked on a table for the enjoyment of voyeurs, things get a bit more complicated. Would the guise of ghastly historical reenactment be enough to justify such a problematic spectacle?

It would take a while to find out. Before the hanging proper, the audience was ushered into pre-show holding rooms, where period-dress wenches served sausages and beer. Hay bales, lit by flickering fake candles, provided the seating. But soon enough it was time to move. The drums sounded, the condemned appeared with her executioner, and the procession to the gallows began. An overzealous audience member shouted “string her up.” Uncomfortably, I fell in line.

anatomy theater at BRIC. Photo: Craig T. Matthew.

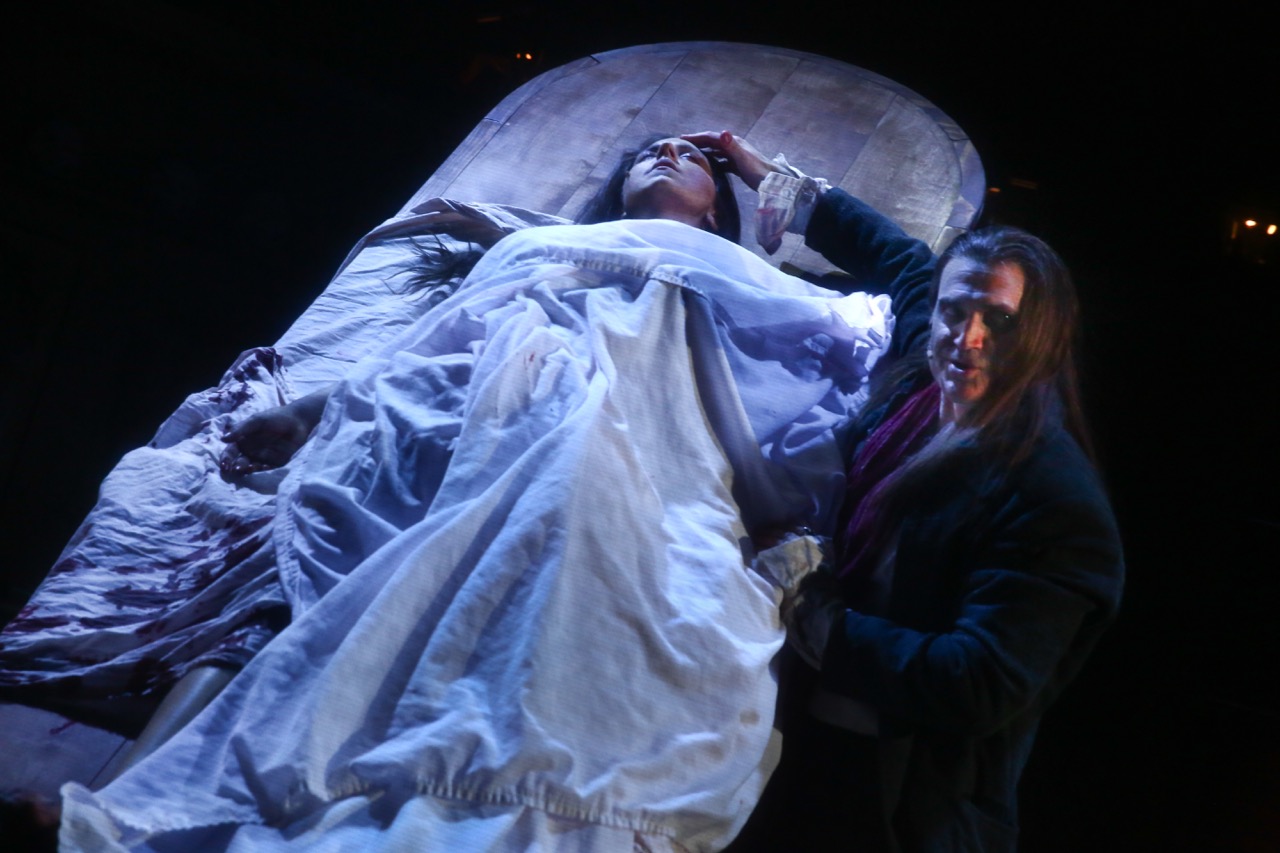

In the theater, where the noose was readied, the condemned (mezzo soprano Peabody Southwell) stood shackled and quivering. Her subsequent confession of murder—a paroxysm of vitriol, regret, and fear—would prove to be the musical highlight of the evening. Southwell’s range is almost unsettlingly huge, a Bruegelesque continuum of forsaken and redeemed realms. Gravelly lows conveyed bitterness as a victim of rape and physical abuse, while rich, round operatic highs suggested remorse at smothering her children. Angel and devil each had their timbre. Like her life, her confession was over too soon.

But there was still that spleen to get to. The master of ceremonies for the evening would be the broad-chested Joshua Crouch (the resonantly voiced baritone Marc Kudisch), a cartoonish carnival-barker type whose job was to set the stage for the proceedings to come, addressing BRIC’s audience as if they were that old-time rabble. If he was something of a musical-theater caricature, he also represented the show’s darkest truths. In one of the more memorable sequences, a physician and his assistant enumerated the fifteen instruments that would be used during the proceedings. As they sang of “penetrating the flesh,” Crouch simulated masturbation while leering at the bare-breasted corpse. It was garish, and yet it revealed what had until then only been a subtext: the proximity of female public dissection to sexual violence itself, with no sharper instrument than the audience’s gaze. But more on that below.

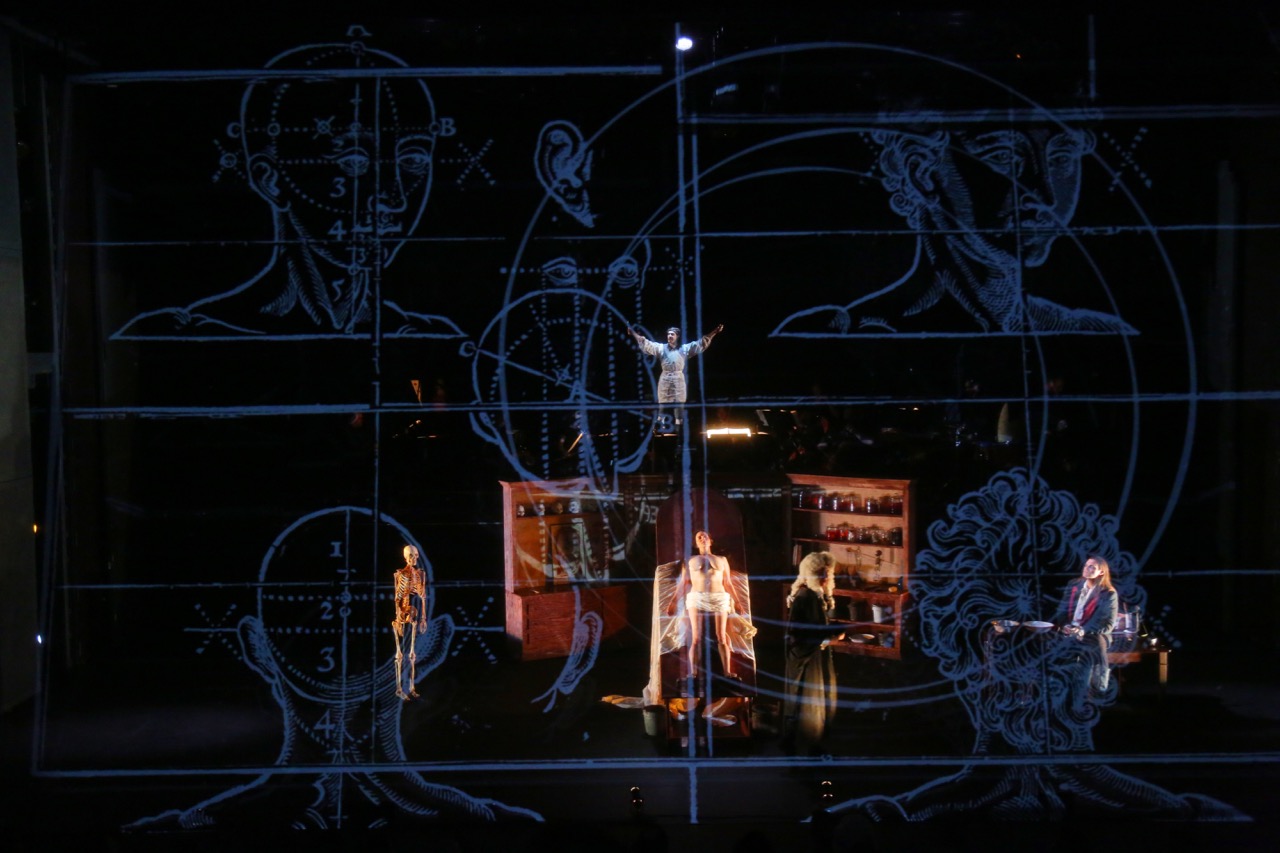

anatomy theater at BRIC. Photo: Paula Court.

As the cutting commenced, out popped the organs, each inspected for moral abnormalities by a dutiful yet skeptical assistant, played by the sensitive tenor Timur. Baritone Robert Osborne was serviceable if a bit stiff as the assistant’s expert anatomist-boss, bent on finding the evil in the fallen Eve. Co-creator and co-librettist Mark Dion, known for his critiques of historical science but here in more of a Disney mode, contributed the cabinet-of-curiosities set design, complete with the requisite skulls on shelves and organs in jars. And the Ridge Theater team worked its reliable magic: projections of historical woodcuts and drawings from Laurie Olinder, subjected to expressionist decay by the filmmaker Bill Morrison; competent direction by Bob McGrath.

anatomy theater at BRIC. Photo: Craig T. Matthew.

As for the music itself, it was in some ways uncharacteristic for Lang. He is notoriously self-effacing and his music can be egoless to a fault when it isn’t beautiful in that austerity. It was interesting, then, to hear such a pared-down post-minimalism put in the service of unabashed musical theater, where restraint so often goes to die. It largely worked. Minor-key ostinatos flirted with a kind of neo-baroque restlessness that complemented the powdered wigs and search for black bile. A chamber ensemble, led by Christopher Rountree and made up of members from the International Contemporary Ensemble, played it all with appropriately surgical precision.

Yet the question of how to deal with the show’s objectified victim remained. In certain types of socially conscious theater, works must be careful not to reproduce the very spectacles that they claim, if only indirectly, to be critiquing. But because anatomy theater was by definition that spectacle, it had to find a way to critique itself. It did so via an unlikely intervention by that self-pleasuring master of ceremonies. Early on, as the killer swung in her noose, he reminded the audience of its complicity in what had and would happen. “Not one soul here cried out ‘Mercy!’” he bellowed, before indicting the crowd of a lurid voyeurism not unlike his own. It felt real. From that moment on, the audience was the true guilty party.

Robert Jackson Wood is a Brooklyn-based freelance writer. He has written for The Brooklyn Rail, the Brooklyn Academy of Music, WQXR radio, and French Institute Alliance Française, among other publications and places. He holds a PhD in musicology from the CUNY Graduate Center, with a dissertation on modernism and composer Edgard Varèse.