Robert Jackson Wood

Robert Jackson Wood

The Calder Quartet tackles the composer’s “nightmare” six-hour epic.

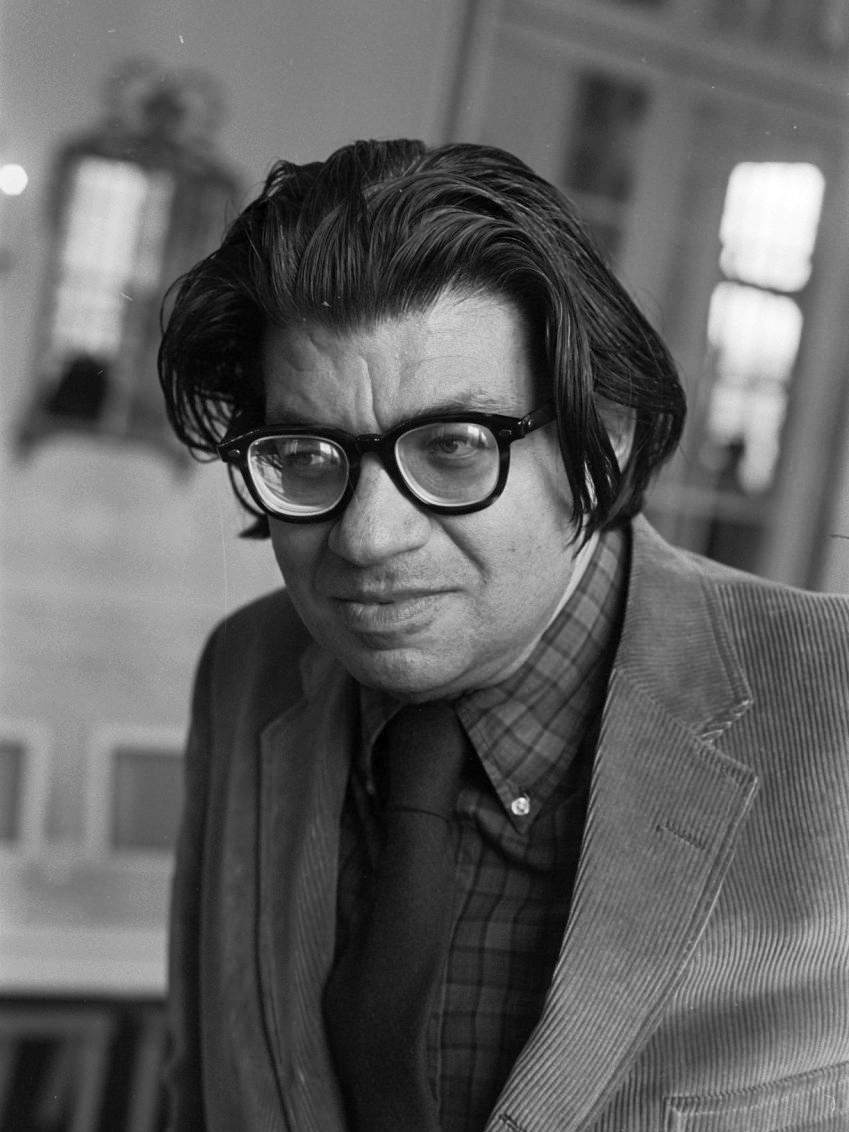

Morton Feldman (Holland Festival 1976). Image courtesy the Dutch National Archives.

Morton Feldman: String Quartet no. 2, the Calder Quartet, the Cloisters, New York City, November 12, 2016

• • •

“What the world doesn’t need is another twenty-five-minute composition,” composer Morton Feldman barked in a lecture given in 1982. Part of the problem was listening habits. There were too many ingrained ways of hearing associated with the half-hour work, preventing more immediate encounters with sound. What was needed instead, he felt, was more time for sounds to breathe, more time to heed the present, more time for time itself.

Six hours would do just fine.

Completed in 1983, Feldman’s epic String Quartet no. 2 is in some respects typical of his late works. Motifs repeat with the slightest variations, bowed just on the edge of tone, before yielding to other, seemingly arbitrary, patterns. There is no continuity, only displacement. On and on the procession goes.

The work’s epic length, though, makes it exceptional, both in the context of Feldman’s oeuvre and the string quartet repertoire in general. It also makes it nearly impossible to play. There are no breaks for the performers, except for an occasional pause between patterns. There are no places where concentration can wane, given the tricky rhythms and delicate textures that must be sustained. The Kronos Quartet, for whom the piece was written, was to give the unabridged world premiere in 1996, but conceded an eleventh-hour defeat. “In our rehearsals we discovered that we are now unable to perform the work for purely physical reasons,” their press release confessed. The world would have to wait until 1999—in a performance by the Flux Quartet, sixteen years after the piece was written—for a full unveiling.

On November 12, in the austere chapel-cum-performance space up at the Cloisters, the Calder Quartet seemed undaunted. This was just another concert, if their smart black ties and dutiful bows were to be believed. Yet the massive crucifix dangling over their heads was hard to ignore. At this particular altar of the “sound of the sounds themselves,” as Feldman called his obsession, perhaps a modicum of faith, if not sacrifice, would also be in order.

The Fuentidueña Chapel at The Met Cloisters. Image courtesy the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

In the opening bars, the high strings move ploddingly within a tight cluster of dissonant pitches—the swing of a deliciously rusty gate. It is a disconcerting way to begin a marathon, perhaps, but it has a purpose: to clear the ear of expectation and instantly set the terms for the listening to come. In the Calder’s rendition, a sensitive attention to voicing mitigated the astringent effect, as did a lilting tempo. The sound was relaxed, but focused.

Eventually, the patterns became more aerated. A six-note motif floated up and down a ladder of shimmering harmonics. Then, a moribund march of pizzicato in the mud. Then, tendrils of high partials, stretched thin like spider webs catching sun. Timbre and texture are everything here, components of what Feldman called the “breathing of sound.” At the performance, though, I strained to hear both adequately, as I did to hear many of the minute rhythmic details that lend these patterns their internal life. The room’s baseline level of ambient noise was partially to blame, and it was hard to say whether the musicians might have compensated with more assertive attacks or presence. My guess is that they couldn’t have. Feldman’s fragile textures simply don’t translate into a stage voice. It’s one of the reasons he was jealous of painters, whose works had only to be seen, and at whatever intimate distance, without the need for intermediary theatrics.

But the problem faded. Or I became hypnotized—one or the other.

Those intermediary theatrics raised other interesting issues, though. To really hear the “breathing of sound” requires a kind of devotional listening. There can be no hoping that the music will develop or resolve, do something or go somewhere. Anticipation must yield to immersion. Against such focused calm, the gestures of the musicians can have an outsized influence on how the music is heard. A raised eyebrow can render a note quizzical. A slight sway can evoke inertia. An early cue can foil a surprise. At times during the Calder’s performance, I closed my eyes, wanting to experience the music more on its own terms. Perhaps that’s the reason the performers closed theirs as well.

Calder Quartet performance at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Image courtesy MetLiveArts.

Behind them, the staggered stones of the chapel wall mimicked the modular structure of the score. On the left, four statues of saints assumed varying states of repose, listening along. The bearded one leaned on his hand and cane, but the performers showed fewer signs of fatigue. On two occasions, Andrew Bulbrook dropped his violin from his shoulder and played it low, fiddle-like. On another, violinist Benjamin Jacobson attempted a drink of water but ran out of time (the cap was screwed on). Hour to hour, the attention to detail was unwavering. A two-note motif with a hairpin crescendo. Again with a hint of vibrato. Again as a vapor. Again as a breath.

It is hard not to hear resignation in this music, particularly right now. After all, the revolution is over, as Feldman said of music since John Cage. Yet on one occasion, Feldman described the second quartet not as a respite or coda but as a nightmare. “It’s like a jigsaw puzzle that every piece you put in fits, and then when you finish it, you see that it’s not the picture. . . . Then you do another version and it’s not the picture. Finally you realize that you are not going to get a picture.”

At the Cloisters, where the audience could come and go as it pleased, listeners seemed satisfied with just the puzzle pieces, each a world unto itself. Yet nightmares are interior dramas. Given the political climate, anyone who secretly sat hoping that fragments might, in this case, yield a more convincing picture could have been forgiven.

Robert Jackson Wood is a Brooklyn-based freelance writer. He has written for The Brooklyn Rail, the Brooklyn Academy of Music, WQXR radio, and French Institute Alliance Française, among other publications and places. He holds a PhD in musicology from the CUNY Graduate Center, with a dissertation on modernism and composer Edgard Varèse.