Steven Zultanski

Steven Zultanski

Race, rodents, and redlining: Theo Anthony’s documentary looks at the troubled history of Baltimore.

Baby rats in Theo Anthony’s Rat Film. Photo: MEMORY.

Rat Film, directed by Theo Anthony, Film Society of Lincoln Center, September 15–29, 2017

• • •

From the flurry of sequences that launches Rat Film, Theo Anthony’s experimental documentary about segregation in Baltimore, it’s immediately apparent that the film is constructed from juxtapositions: a race car starts its engine while a deadpan voiceover reads a creation myth about how the world began as an egg, a trapped rat desperately attempts to jump out of a trash can, a pixilated Google Earth version of the city slowly scrolls by, the narrator provides a brief lesson on rat neurology, and a pair of hands plays a synthesizer. The film slows down some after this initial sprint, giving more space to the city’s past and the interviewees’ experiences there, but it maintains its briskness throughout by frequently shifting between subjects (some closely related, and some tangential). While its structure is disjunctive, Rat Film ultimately makes an argument about cause and effect, finding the roots of Baltimore’s Norway rat infestation in the practice of redlining (a mapmaking strategy used by insurance companies and lenders to circumscribe neighborhoods based on race and class).

Harold Edmond in Theo Anthony’s Rat Film. Photo: MEMORY.

Early on, a worker for the city’s Rat Rubout program, Harold Edmond—a charismatic talker who is a main character and dispenser of wisdom—succinctly articulates the film’s position: “It ain’t never been a rat problem in Baltimore, it’s always been a people problem.” Edmond explains many of the nitty-gritty details about infestation and extermination, but also philosophizes about the lives and struggles of the people who live in systemic poverty, for whom the rats, though particularly disgusting, are only one obstacle among many. The cast of personalities portrays a range of strategies that humans use to adapt to environments that have been ravaged by racial and economic oppression: a man who sells baby rodents as food for reptiles, a quirky family that rearranged its home to make sure their pet rats can’t escape, two guys who spend nights fishing rats for sport, using lunchmeat and peanut butter as bait.

Greg and Will Kearney in Theo Anthony’s Rat Film. Photo: MEMORY.

Just as these interviewees represent a swath of Baltimore culture, Baltimore itself functions as a metonym for the US. The film narrates a series of “firsts” that neatly compress key elements of twentieth-century US urban history: the city enacted the first legislation in the country that prevented black people from moving into majority white neighborhoods, and white people from moving into majority black neighborhoods to stop integration (1911); the first US-made rat poison was invented by a doctor at Johns Hopkins (1942); and the city pursued the first government pest-control program in the nation, in which experimental rodent poisons, whose effects on humans were unknown, were tested in predominantly black neighborhoods (also 1942).

Political decisions and scientific research are portrayed as interlocking components of the same history. Halfway through Rat Film, when it’s still uncertain how all the different narrative threads will be tied together, Anthony inserts a clear story that makes an unambiguous political point. The doctor who developed the first rat poison and ran those unethical tests was psychobiologist Curt Richter, who also wrote a eugenicist paper titled “Rats, Man, and the Welfare State,” which compared rat behavior to human behavior in order to argue that government support for the poor led to weakness and dependency. He was ideologically opposed to state investment in poverty-stricken neighborhoods that might improve conditions and used the cover of science to promote an ineffective rat poisoning program that was both potentially toxic and contributed to a long-term health hazard. When his colleague at Johns Hopkins, David E. Davis, argued that the rodents’ spread was environmentally determined and could be restrained by more humane housing and infrastructure, Richter pushed back, arguing that aggressive poisoning campaigns were the only solution.

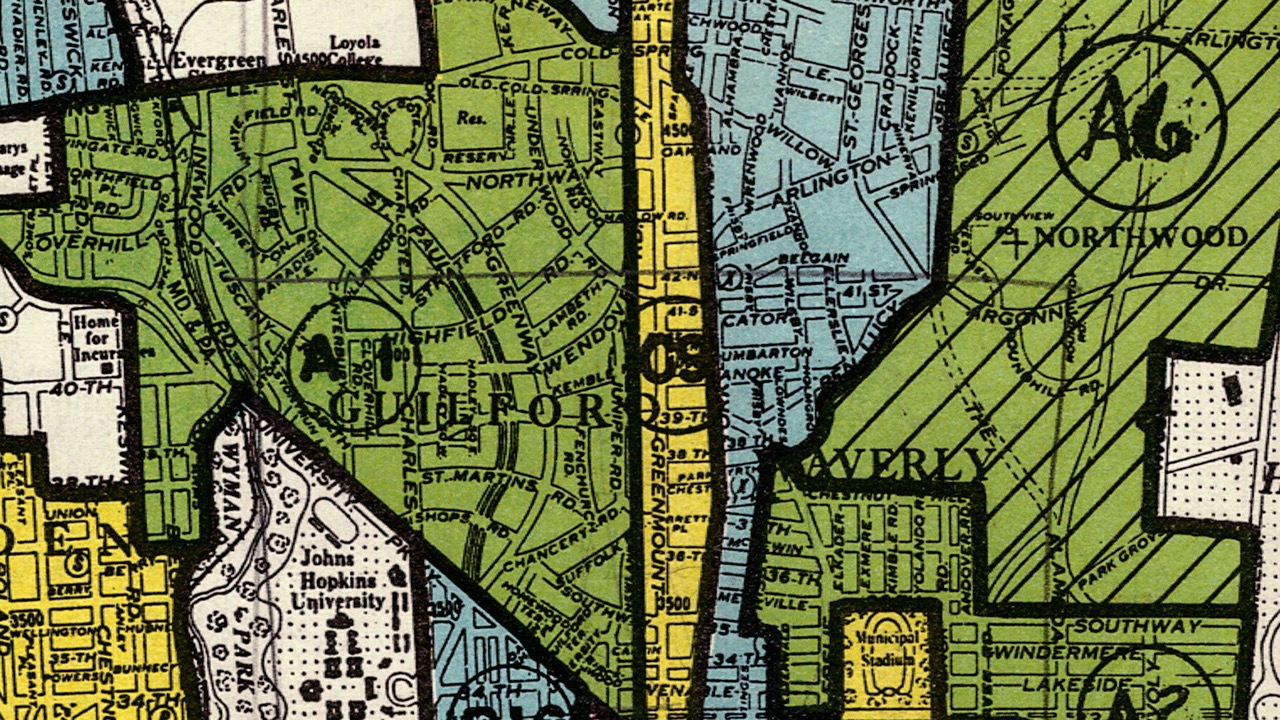

Map of Baltimore in Theo Anthony’s Rat Film. Photo: MEMORY.

In an illustrative parallel, Anthony then shows how financial interests used the cover of economic rationality to enforce segregation. In 1937, a “residential security” map commissioned by the Homeowner’s Loan Corporation (HLC) divided the city by race and class, carving out areas considered too risky for bank loans and undesirable for investment. People in these areas were subsequently denied loans, so that they found it difficult or impossible to move; this initial map determined eighty years of segregation and impoverishment. In one of its final passages, Rat Film overlays maps of Baltimore’s ills in 2015—maps titled “Arrests,” “Vacant Homes,” “Neighborhoods Below the Poverty Line,” “Neighborhoods where the Unemployment Rate is Double or Greater than the National Average,” and “Neighborhoods where Average Life Expectancy is One Standard Deviation Below the City Average”—on top of the 1937 HLC map. They correlate nearly exactly. A voiceover dryly pronounces: “New maps. Old maps. Same maps.”

Against the illusion of capitalism’s neutrality, Rat Film’s juxtaposition of historical detail, personal experience, and formal experimentation suggests a way of mapping and constructing history that is intentionally partial, positioned, and open-ended. This accounts for the inclusion of footage from Google Maps: rather than marveling at the technology, the film gleefully explores the visuals produced at the edges of the code, where the graphics break down and the images seem to fall into abstract space (as when the user tries to see under a street or into a structure). These scenes play with the limits of corporate mapping; they use these glitches to show that such mapping is not total, and to aestheticize incompleteness.

Baby rat and snake in Theo Anthony’s Rat Film. Photo: MEMORY.

In this spirit, a number of the formal elements are not easily reconciled with the rest of the film: the comically flat intonation of the voiceover, the occasional jarring cut or unexpected freeze-frame, and the synthesizer score. These loose ends are entertaining and thought-provoking (as one tries to tie them all together), but Anthony’s agile and associative editing is what really gives Rat Film its buoyancy. The fast-paced tonal shifts deftly draw parallels between sometimes disparate content (psychological research and infrastructural policy; extermination and pet ownership), building continuously changing relationships between topics. Rat Film depicts reality, but not a static reality: both entrenched segregation and the rat infestation seem like intractable problems, but the interviewees’ wide-ranging philosophical statements about daily struggle, the creation myth that opens the film, and the images that conjure “big” themes like good-and-evil and life-and-death (for example, a snake slowly eating a baby rodent) all point toward a longer history and new beginnings. The film is overflowing with possible metaphors for change, which is hopeful, even if metaphors are not enough. After all, the rats, like the ugly history of racism and profit, don’t stand in for anything.

Steven Zultanski is the author of four books of poetry, most recently Bribery (Ugly Duckling Press, 2014) and Agony (BookThug, 2012). His critical writing has appeared in Art in America, Convolutions, Los Angeles Review of Books, Mousse, and elsewhere. In January 2017, an art exhibition inspired by his writing, titled You can tell I’m alive and well because I weep continuously., showed at the Knockdown Center in Queens.