Rumaan Alam

Rumaan Alam

Pier Paolo Pasolini’s 1955 debut novel tells the defiant stories of the scheming and dreaming street kids of postwar Rome.

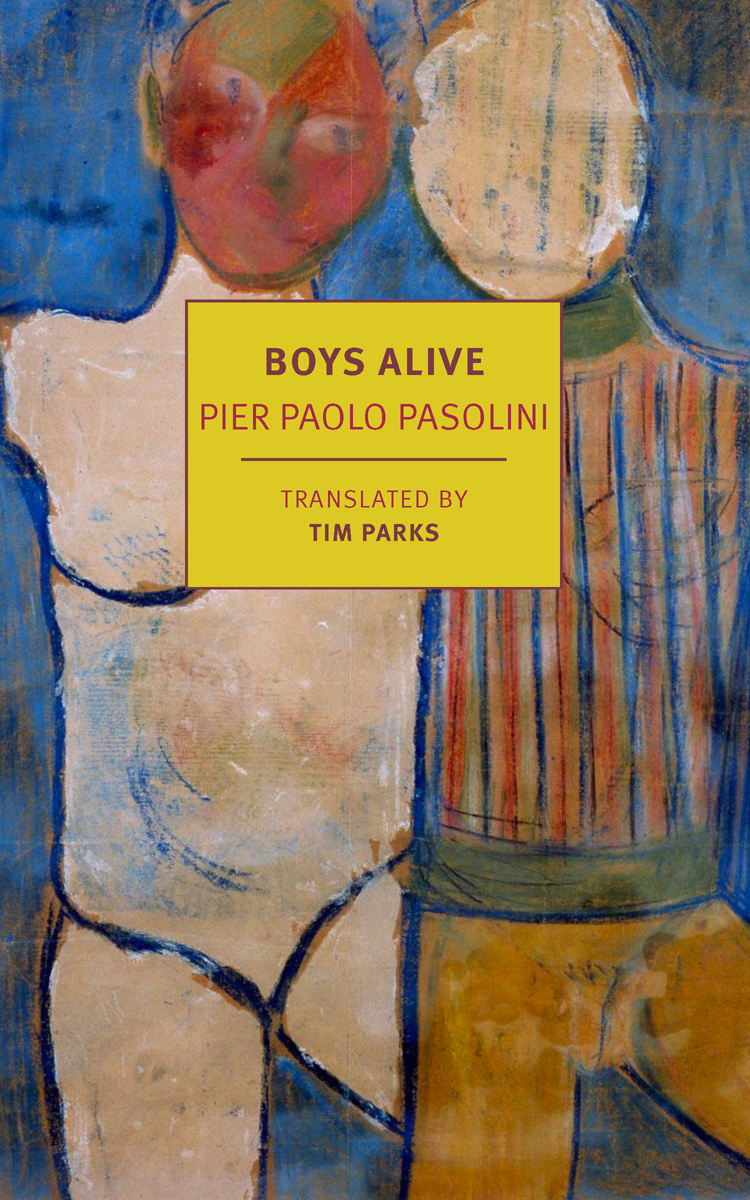

Boys Alive, by Pier Paolo Pasolini, translated by Tim Parks, New York Review Books, 209 pages, $16.95

• • •

Youth and vitality are synonymous enough that the title of Pier Paolo Pasolini’s first novel, Boys Alive, seems redundant. Boys are alive by definition. But this is how translator Tim Parks has chosen to render Pasolini’s phrase Ragazzi di vita (said to be an idiom for “hustlers”; for her 2016 translation, Ann Goldstein settled on The Street Kids). Maybe Parks is onto something. In the postwar Italy Pasolini conjures—the book was first published in 1955—life, even for boys, is not a given. In these pages, Rome’s war-scarred cityscape reminds us that death ever looms, and many of the boys we meet come to a grim end. But those boys, nevertheless, carouse, steal, and fuck; maybe that’s being alive. “They wanted,” Pasolini writes, “if anything, to defy the world in general, that whole race of people who didn’t know how to enjoy themselves the way they did.”

Boys Alive opens with a lad called Riccetto (“curly,” per Parks’s helpfully orienting introduction) slipping out of church, where he’s just been confirmed, to join a crowd that is looting a nearby factory. The next day, Riccetto and his pal Marcello show up at a similar scene forming at the general markets: “through barred windows you could see heaps of bike tires and inner tubes, tarpaulins, canvas, and, on the shelves, whole cheeses.” If you didn’t already understand that these boys have chosen the profane over the sacred, a woman dies in the melee, and Marcello “jumped over the corpse, rushed into the basement, and filled his bag with tires, along with other boys grabbing everything they could.”

Riccetto isn’t precisely the novel’s protagonist; he’s merely the most recognizable of a loose coalition: Agnolo, Marcello, Alvaro, Amerigo, and others—enough players to stymie the reader who wants a hero. It’s never exactly clear what these boys look like, and often their age, too, is vague. This is an earlier understanding of adolescence; these aren’t children, quite, but fledgling adults: aimless and impoverished, congregating in parks and scheming for money, hunting for cigarette ends or “wandering around the market stalls like a stray dog, sniffing at the smells that wafted about by the thousands on the haze of the sirocco.”

Pasolini is attentive to geography—“they idled away the afternoons, at Donna Olimpia or on Monte di Casadio, among the other kids playing on the small sun-blanched knoll . . . Or they went to play football in the clearing between the Grattacieli and Monte di Splendore . . . or on the parched grass beside Via Ozanam or Via Donna Olimpia.” His scene setting has the specificity of GPS-generated driving directions. It reminded me of how Patrick Modiano writes about Paris: both men provide a litany of street names and identifying markers meaningful only to the native (even then, perhaps not).

Neither writer uses this geography to orient the reader, to help her see. Each maps their characters’ literal ramblings instead of their psychic peregrinations. The Eternal City, at least in 1955, is looking a little worse for wear: “In the silence, between big walls that stank of piss in the heat, the Tiber flowed yellow, as if driven by the refuse it bore down in plenty.” Early in the book, the local school collapses: “On the right-hand corner where the school building had been was a huge, still-smoking ruin with a mountain of whitish rubble and chunks of cement on the road.” In a crumbling world, defiance seems only just. The kids are not alright, and who can blame them?

Boys Alive resists a certain kind of reader—I’m one, I confess—by offering a series of episodes rather than a single plot. Some of these anecdotes are sweet (if you’re the sort who is charmed by the dumb things kids the world over get up to): group of boys are so enchanted by a dog that some of them “started laughing and rolling around on the grass like the puppies.” Some are grimly comic, as when Amerigo tries to outrun a gambling bust and ends up dead (it’s funny, trust me). Some are horrific, as when a drifter recounts watching a pair of men immolate two women: “We’re hearing screams and more screams and we go in there and see these two whores all on fire.”

Parks’s introduction provides context I found useful, from Pasolini’s frankness about his homosexuality to a sexual indiscretion (group masturbation with three underage boys) that left him ostracized: “I was tarred with the brush of Rimbaud . . . or even Oscar Wilde.” Pasolini’s original publisher asked for revisions—less Roman dialect, less obscenity. Parks argues that the author, in obeying this, also refined other aspects of the text. Hard to know what the authoritative source material is, let alone how to translate a dialect that even Italian speakers might find impenetrable. This is the trap for readers in translation—master another tongue or accept that you can only experience a text as interpreted by another. Still, I found this edition’s language persuasively youthful, energetic, propulsive.

Pasolini isn’t a moralist like Graham Greene, whose 1954 “The Destructors” is a landmark in the literature of boys behaving badly. In that story, one teen’s desire to tear down his neighbor’s home is no different than nocturnal emission or other plights of the adolescent. “It was as though this plan had been with him all his life, pondered through the seasons, now in his fifteenth year crystallized with the pain of puberty.” Pasolini’s kids are up to no good, but it’s adulthood that’s truly grotesque: “There was a fat woman with folds of flesh pushing from under her cream silk dress, lips sugary from the buns she’d been eating, and a boiled fish of a face, and beside her an ugly little thing, her husband maybe, who had a fried fish of a face, poor guy, struggling with a hangover.”

I had steeled myself for a book that was filthy, as anyone who has seen Pasolini’s film Salò might. Even if Pasolini’s original publisher thought it was, I found the author’s occasional descriptions of the boys herein, if not exactly chaste, almost touching: “They were in their work clothes, since they hadn’t washed yet, canvas pants loose at the crotch and tight at the ankles, their legs moving inside like flowers in a vase, or crossed the way soldiers cross their legs in photographs.” Times change, as do standards. I don’t doubt that Pasolini might have felt some sexual frisson for these boys, brawling, strutting, expectorating. But he saw, too, that they were like flowers in a vase: beautiful.

Rumaan Alam is the author of the novels Rich and Pretty, That Kind of Mother, and Leave the World Behind.