Aruna D’Souza

Aruna D’Souza

Colored-pencil works by the Inuk artist present an imaginative worldview combining cultural traditions and a dreamlike reality.

Shuvinai Ashoona: Looking Out, Looking In, installation view. Courtesy the artist and Fort Gansevoort. © Shuvinai Ashoona. Pictured, center: Drawing like the elephant, 2023.

Shuvinai Ashoona: Looking Out, Looking In, Fort Gansevoort,

5 Ninth Avenue, New York City, through November 4, 2023

• • •

Like so many born and raised in Canada, my sense of national identity is inseparable from the North, which makes up forty percent of the country’s landmass. In the social imaginary, the Arctic region is a mythical place, sparsely populated by happy people untouched by modernity, its landscape the very definition of the sublime—immense and gorgeous and terrifying. That myth, no matter how charming when I saw it trotted out in Sesame Street segments (Canadian content!), is an instrument of settler colonialism, of course, and has obscured a deep history of dispossession and cultural erasure, of deprivation and callous inhumanity toward Inuit, and of exploitation of the area’s resources. It is a myth, too, that has until recently influenced what kind of art was created among Arctic communities for collectors, who have constantly been on the lookout for “authenticity”—a word most accurately defined as “stuff that confirms the myth we created about you in the first place.”

Shuvinai Ashoona, Moving with our campsites (traditional movers), 2023. Colored pencil and ink on paper, 50 × 96 inches. Courtesy the artist and Fort Gansevoort. © Shuvinai Ashoona.

There’s a trap set for the colonized, no matter where they’re from: the only way to counter such a self-serving fantasy is by opening oneself up to the colonizer’s voracious gaze—tell us what life is really like, then. Certainly, telling one’s own story can be empowering and important and necessary—but the insistence on transparency is extractive and invasive, given that it is always presented as a precondition for the colonizer’s belief in one’s humanity. (Édouard Glissant is a great read on this subject, as well as the Stó:lō/Skwah writer Dylan Robinson, whose 2020 book Hungry Listening, on Indigenous sound practices, I cannot stop talking about.)

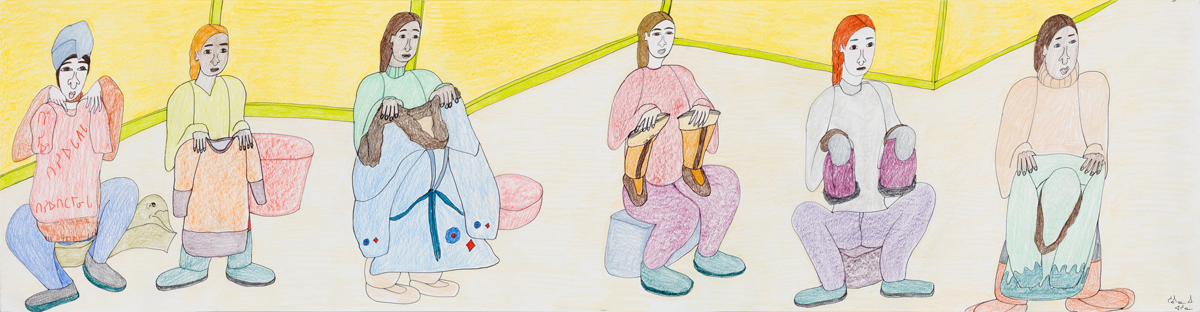

Shuvinai Ashoona, Holding what they made in town, 2022–23. Colored pencil and ink on paper, 13 × 50 inches. Courtesy the artist and Fort Gansevoort. © Shuvinai Ashoona.

What I find so striking about Inuk artist Shuvinai Ashoona’s show of recent work at Fort Gansevoort—her first major outing in New York—is the way she sidesteps such a demand, whether intentionally or not. Her meticulous drawings in colored pencil and ink, some of them panoramic in scale, draw from a deep well of cultural tradition without being restricted to it, and depict present-day life without functioning as mere documentary for curious audiences. She doesn’t counter the colonizer’s myth with reality, but with a new, contemporary Inuit mythology, one replete with imaginative, dreamlike, even whimsical ways of conveying her worldview.

Shuvinai Ashoona, Polar bear sketching people, 2023. Colored pencil and ink on paper, 50 1/4 × 97 1/4 inches. Courtesy the artist and Fort Gansevoort. © Shuvinai Ashoona.

Take, for example, Polar bear sketching people (2023). Measuring just over eight feet long, it offers insight into the material conditions of Ashoona’s creative practice. Her family settled in Kinngait (formerly Cape Dorset), off the southwestern tip of Baffin Island, after commercial overfishing and the collapse of the fur trade had rendered nomadic existence untenable. To replace this lost sustenance, people of her grandparents’ generation were encouraged by government agencies and a few key figures from the south to turn to artmaking. They began translating the graceful linearity of their traditional small-scale stone carving into lino- and stone-cut printmaking, large sculptures, and drawings that satisfied the tastes of collectors from Canada’s urban centers. In 1959, the community established the West Baffin Eskimo Cooperative, which provided ready money for artists by immediately purchasing their work before sending it to other parts of Canada to be sold; the profits would later be redistributed to the community in the form of dividends. To ensure against lean times in the art market, the cooperative added a restaurant, a general store, and the administration of the town’s utility contracts to its profit-sharing scheme; in 2019, it built a state-of-the-art studio, cultural center, and exhibition space. Over the years, this shared endeavor has allowed Kinngait to become the North’s most important center for Inuit art, and has nurtured generations of celebrated artists, including Ashoona’s grandmother, Pitseolak Ashoona, mother, Sorosilutu Ashoona, and cousin, Annie Pootoogook. In a community of 1,400 people, an extraordinary number—ten percent or so—are professional artists.

Shuvinai Ashoona: Looking Out, Looking In, installation view. Courtesy the artist and Fort Gansevoort. © Shuvinai Ashoona. Pictured: Made my clothing at clothing centre, 2022–23.

Polar bear sketching people presents some signs of this reality: a framed window opens up onto a printmaking studio with an artist inside, and an ink roller and lithograph in process; sitting on benches outside, some of Ashoona’s artist-friends show off their work to us, the viewers, who are subtly positioned as potential buyers. (The frankness about the economic imperative attached to artmaking, which pops up as well in Holding what they made in town and Made my clothing at clothing centre, both 2022–23, is refreshing and poignant at once—art is a matter of survival in a place like Kinngait, which has been systematically impoverished by settler colonialism.) But one of these artists is a furry yellow animal, clutching a sketch of bug-like critters making paintings—one of an art studio, another of an ocean scene. The drawings held by her human friends portray a polar bear painting a flower and rabbits and a brown goose raising up their work for viewers to admire. In the upper right corner, through another window, walruses and other sea animals wield stone-carving tools, while a squid-like creature with a whale’s baleen for a mouth dances on the pale green grass in the foreground. This surrealistic, mise en abyme structure, which appears in a number of smaller works in the show, including Drawing like the elephant (2023), turns the picture’s surface into a series of portals, in which the lines between human, natural, and even supernatural are rendered meaningless. Creativity is not what sets us apart from other beings, but what ties us to them.

Shuvinai Ashoona: Looking Out, Looking In, installation view. Courtesy the artist and Fort Gansevoort. © Shuvinai Ashoona. Pictured, center: Eggs and Rocks, 2023.

When the New York Times profiled Ashoona last year, it published as its hero image a photo of Kinngait that, not unexpectedly, emphasized its remoteness, vast skyline, eerie, constant twilight, and forbidding climate. When the artist turns to that same landscape in her drawings, the effect is entirely different. Images like Moving with our campsites (traditional movers) and Eggs and Rocks (both 2023) show a place that is not barren but replete. The first portrays a group of people dressed in traditional animal-skin clothing walking over ice floes and rowing kayaks loaded with their belongings. (The coexistence of long-standing cultural traditions and the trappings of modern life is indicated, subtly, by the sail of the leading boat, which is printed with a Canada Post postal code.) The second depicts a snowless expanse of irregular boulders separated by rivulets of pebbles and a pond, with birds swimming, sunbathing, or tucking themselves under and between the stones. In both cases, the horizonless composition confounds the eye. We look down on the scene without exactly having a bird’s-eye view: the landscape seems to project toward us, almost cradling us at some points, destabilizing us at others; it’s not still and frozen but active and roiling. When Ashoona trains her gaze on particularities—as she does, for example, in Eggs and Rocks, where she delineates the pebbles one by one in almost impossible detail—she paradoxically pushes the image toward abstraction. For those of us who have only experienced the Arctic through photographs—and that includes almost all of us, I would think—her eccentric subjects and complex spatial gambits result in images that challenge settler-colonial terms of representation. In these pictures, the North is not empty and therefore free for the taking, but is on the contrary teeming with life, human and otherwise.

Aruna D’Souza is a writer and critic based in New York. She contributes to the New York Times and 4Columns, and is author of Whitewalling: Art, Race & Protest in 3 Acts (Badlands Unlimited, 2018). She is currently working on a new book, Seven Pictures for a New World, and a volume of collected essays.