Melissa Anderson

Melissa Anderson

Naked and unafraid: the unsung Corman-protégé’s search for sexual freedom within the exploitation genre.

Celeste Yarnall as Diane LeFanu in The Velvet Vampire. Courtesy the American Genre Film Archive.

“The Films of Stephanie Rothman,” Spectacle Theater, 124 South Third Street, Brooklyn, NY, through September 30, 2023

• • •

New Hollywood may be old, but its legacy remains only partially explored. That vaunted era in American cinema, roughly dating from the late 1960s to the late ’70s, saw the release of the first features directed by mavericks such as Martin Scorsese, Francis Ford Coppola, and Peter Bogdanovich. They got their start in filmmaking by working for the B-movie maestro Roger Corman, who, whether as a director or producer, churned out scores of lurid cheapies with titles like Devil’s Angels and Bloody Mama. So crucial was Corman to the genesis of this epochal shift in US cinema that he has been dubbed “the spiritual godfather of the New Hollywood.”

Jerry Daniels as Juan and Sherry Miles as Susan Ritter in The Velvet Vampire. Courtesy the American Genre Film Archive.

That highly mythologized movie decade has almost exclusively been the story of Corman’s celebrated godsons and other brash male auteurs. Largely marginalized in this history is a figure in the Corman coterie who would make films with an authorial stamp as distinct as that found in Mean Streets, The Conversation, or The Last Picture Show but who would never break out of the exploitation-movie circuit. Now eighty-six, Stephanie Rothman, who studied filmmaking at USC in the early ’60s and was the first woman to receive the Directors Guild of America fellowship, began working in 1964 as an assistant to Corman, then a macher with American International Pictures. Her responsibilities grew to include shooting half an hour of original footage for a bohemian splatter-fest called Blood Bath (1966), for which she shared director’s credit with Jack Hill (who would later helm the movies that made Pam Grier the queen of Blaxploitation). Impressed, Corman partially financed Rothman’s first solo directorial effort, It’s a Bikini World (1967).

Karen Carlson as Phred and Barbara Leigh as Priscilla in The Student Nurses. Courtesy the American Genre Film Archive.

I’ve never seen it, but the title alone of that beach-party bonanza is enough to recommend it. Of the five films she made subsequently, four are featured in the Rothman retrospective currently underway at Spectacle, an adventurous micro-cinema in Williamsburg. I endorse every title in the quintet to the fullest (no matter their flaws), above all The Student Nurses (1970), the epitome of the Rothman style: beautifully photographed exploitation films that, while filled with the nudity, violence, and sex mandated by the genre, seriously examine a host of progressive ideas, not least women’s sexual autonomy.

Reni Santoni as Victor Charlie in The Student Nurses. Courtesy the American Genre Film Archive.

The Student Nurses—produced and distributed by Corman’s New World Pictures, and based on an original story that Rothman cowrote with Charles S. Swartz, her husband and frequent collaborator (and another Corman vet)—follows a quartet of RN hopefuls, leggy young women sharing a Los Angeles apartment and inchoate idealistic visions that will become more clearly defined by the time they take their final exam. If the caregivers-in-training seem to shuck their uniforms and civvies a little too often, their beaux are nearly as often filmed in the buff. For all the female flesh bared, though, more screen time is devoted to the sexism the lithe pupils face in the workplace, if not the evils of patriarchy in general; the most astonishing sequence of the film, which premiered three years before Roe v. Wade, centers, quite calmly, on an at-home abortion. Radicalized by an encounter with a Chicano activist, trainee Lynn (Brioni Farrell) wants to dismantle the medical-industrial complex altogether: “People have always gone to hospitals. Now that has to change. No matter what, hospitals have got to go to the people.”

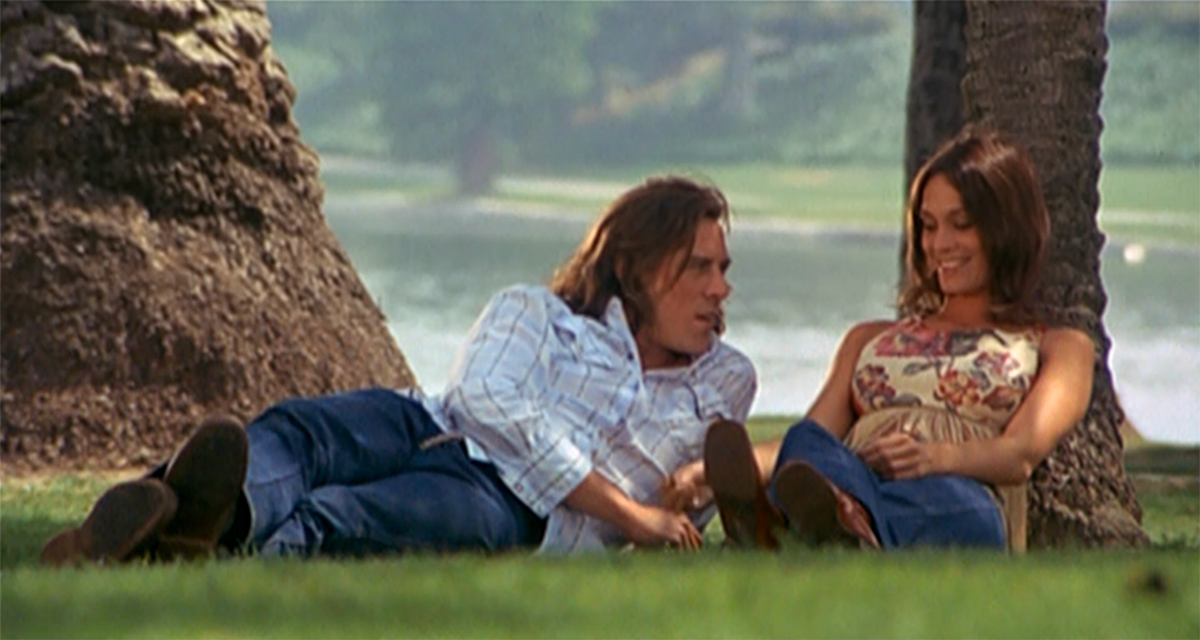

Richard Rust as Les and Barbara Leigh as Priscilla in The Student Nurses. Courtesy the American Genre Film Archive.

Rothman is one of the finest chroniclers of Southern California’s elysian light and scenery; two of the most transporting sequences in The Student Nurses feature the dreamiest of the foursome, Priscilla (Barbara Leigh), at a love-in in MacArthur Park and, later, at the beach, dropping acid for the first time. Occasionally the visual magnificence of Rothman’s films serves as the star attraction, more than compensating for the often awkward acting, which could most charitably be described as “naïve,” least so as “excruciating.” Michael Blodgett and Sherry Miles, who play Lee and Susan, the young married couple seduced by Diane LeFanu (Celeste Yarnall), the lady bloodsucker of the title in California desert–set The Velvet Vampire (1971), for example, are avatars of anti-charisma; both perform as if they spent too much time with Charlie Manson on Spahn Ranch. Yet the retina-searing crimson décor of the chamber from which Diane spies on her prey anticipates the sinister sanguine hue of the Red Room in Twin Peaks, and the film’s lysergic dream sequences seem art directed by de Chirico.

Michael Blodgett as Lee Ritter and Celeste Yarnall as Diane LeFanu in The Velvet Vampire. Courtesy the American Genre Film Archive.

The ménage à trois in The Velvet Vampire is doubled in Group Marriage (1972; not included in the Spectacle series), one of the first films from Dimension Pictures, the production and distribution company that Rothman and Swartz helped establish. Highlighting the splendor of the Pacific Palisades and more SoCal beaches, the film concerns a sexed-up sextet of straights determined to live outside heteropatriarchal norms. But even this libertine arrangement proves too confining for one of the women, who delivers what could stand as the mantra for any of Rothman’s female protagonists: “I gotta be free.”

Ena Hartman as Carmen Simms and Marta Kristen as Lee Phillips in Terminal Island. Courtesy the American Genre Film Archive.

A much more fundamental distaff freedom is at stake in Terminal Island (1973). Taking its name from the isolated land mass where, after the abolition of the death penalty, California now sends prisoners convicted of first-degree murder, this carceral thriller tracks the plight of the four women inmates on the island trying to liberate themselves from sexual slavery. They are aided in their mission by a breakaway faction of enlightened male prisoners who seek to overthrow the atoll’s maniacal leader. What starts out as a dystopian saga—following a prologue sending up the cynicism of TV programmers that’s funnier than anything to be found in Sidney Lumet’s didactic Network, released three years later—ends up as the utopian vision of an egalitarian off-the-grid compound.

Phyllis Davis as Joy Lang, center, in Terminal Island. Courtesy the American Genre Film Archive.

The parity between the sexes intimated at the conclusion of Terminal Island would escape its maker. Rothman never directed another film after 1974’s The Working Girls, about three housemates in LA’s Venice neighborhood, each woman pursuing unconventional professions (such as the law student moonlighting as a stripper). Unlike the male alums of the Corman Academy, Rothman was never given the opportunity to advance to “legitimate” cinema. As she explained in a 2010 interview: “I was stigmatized by the films I had made. The irony was that I made them in order to prove that I had the skills to make more ambitious films, but no one would give me the chance. Then there was the other reason, the so-called elephant in the room: I was a woman. No one told me directly, but I often learned indirectly that this was the decisive reason why many producers wouldn’t agree to meet me.” New Hollywood, antiquated rules.

Melissa Anderson is the film editor of 4Columns and the author of a monograph on David Lynch’s Inland Empire from Fireflies Press.