Aruna D’Souza

Aruna D’Souza

Thirteen international artists respond to the ongoing legacy of trauma, violence, and defiance caused by the 1947 division.

Proposals for a Memorial to Partition, installation view. Courtesy Twelve Gates Arts. Photo: Sahar Irshad.

Proposals for a Memorial to Partition, curated by Murtaza Vali,

Twelve Gates Arts, 106 North Second Street, Philadelphia, PA,

through October 28, 2023

• • •

Partition has cast a long, unrelenting, traumatic shadow on my parents’ generation, on mine, even on my child’s. How could it not? By the time the British Raj was forced to leave South Asia, its divide-and-conquer strategy had made near impossible the creation of a single postcolonial nation in which Hindus, Sikhs, Muslims, and the so-called “untouchable” castes (who adopted the name Dalits) could coexist. And so, in 1947, leaders of these groups drew a line that excised the predominantly Muslim east and west from the Hindu-dominated hulking mass of the subcontinent, forcing tens of millions of people to decide whether to stay in place or go to the land that had been assigned to their coreligionists. Somewhere between fourteen and eighteen million uprooted themselves in a matter of months, resulting in one of the largest mass migrations in human history.

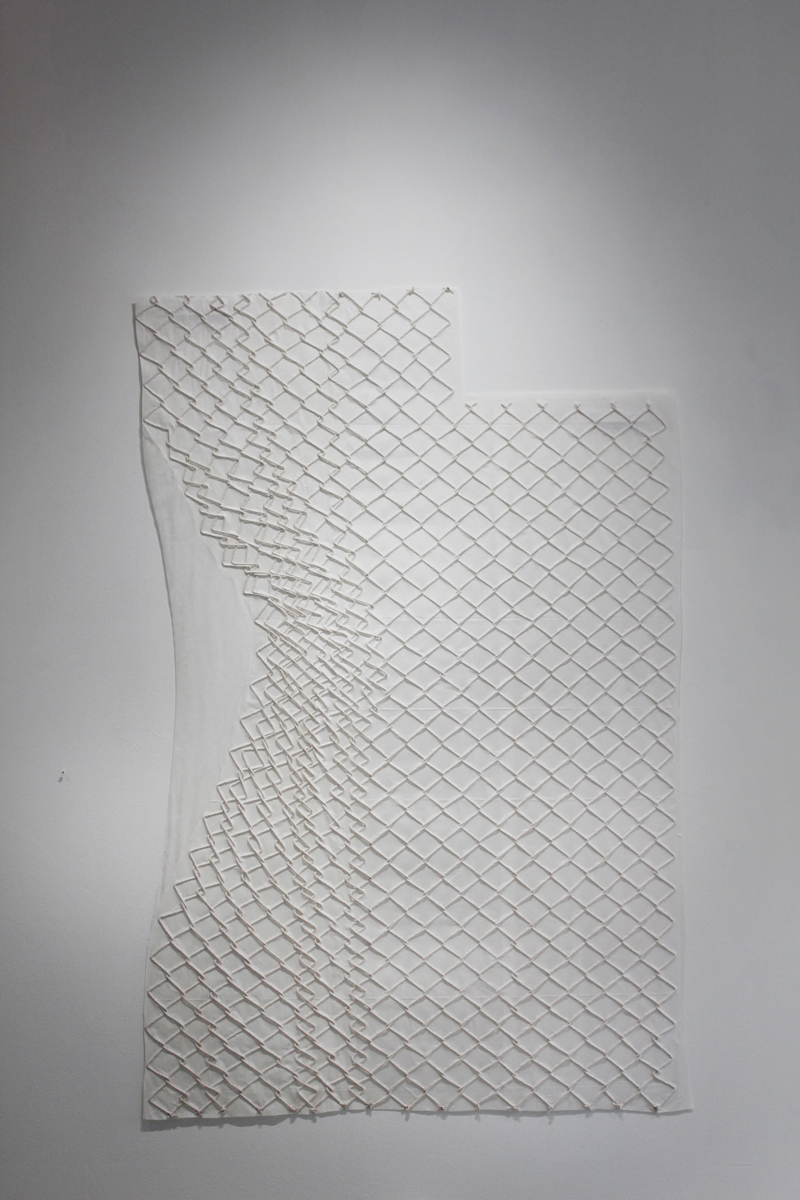

Sreshta Rit Premnath, Catch and Release, 2023. Cotton rope and mulberry paper. Courtesy Twelve Gates Arts. Photo: Sahar Irshad.

More than a million of those migrants died, brutally, at the hands of people who had formerly counted them as neighbors; the stories of the almost inhuman violence enacted upon those crossing the border—rapes, disembowelments, castrations, baby killings—still haunt so many of us, no matter the temporal and geographical distance. But Partition didn’t end there. The subsequent amputation of East Pakistan from West, creating the nation of Bangladesh in 1971; the decades-long aggression between India and Pakistan, which has consumed lives and left places like Kashmir, claimed by both, in a state of siege; the current Hindu nationalism driving Narendra Modi’s fascist rule—all can be traced to the mess the British left behind, a mess many South Asians have had little interest in cleaning up.

Proposals for a Memorial to Partition, installation view. Courtesy Twelve Gates Arts. Photo: Sahar Irshad.

Murtaza Vali, a Brooklyn- and Sharjah-based curator and critic, has organized what he calls a “peripatetic curatorial platform” that explores the cascading effects of this historical cataclysm. Proposals for a Memorial to Partition opened in 2022 at Dubai’s Jameel Arts Centre and now appears, in a new and smaller iteration, at Twelve Gates Arts (a gallery in Philadelphia that focuses on artists from West and South Asia). Thirteen makers from around the globe offer up sculptures, small-scale installations, drawings, paintings, videos, sound recordings, and artist books in the storefront space. Though the title refers to the idea of a memorial, the show eschews almost entirely the oft-related notion of the monumental. Instead, modestly sized works, some as small as a postcard, present opportunities to connect the unhealed wounds of the past to the rawness of the present.

Proposals for a Memorial to Partition, installation view. Courtesy Twelve Gates Arts. Photo: Sahar Irshad. Pictured, far left: Jaret Vadera, a flag for three mothers, 2023.

A flag for three mothers (2023), by Montreal- and Brooklyn-based Jaret Vadera, hangs just outside the gallery’s entrance. If colonialism operated according to a bureaucratic logic of classifying populations, counting and dividing them into subcategories of otherness, Vadera uses such information as a kind of algorithm. The color of his banner, a pale yellowish green, is derived from the various shades of the flags of India, Pakistan, and Bangladesh, each weighted according to their populations, the resulting admixture presented as a monochrome. The piece reads at once as a utopian fantasy of reunification and its opposite: the jaundiced hue that results from Vadera’s process has no vibrancy, no life to it—it is muddied and dull.

Proposals for a Memorial to Partition, installation view. Courtesy Twelve Gates Arts. Photo: Sahar Irshad. Pictured, left to right: Prarthna Singh, Har Shaam Shaheen Bagh. A record of the 100 day protest that took place in New Delhi from December 2019 to March 2020, 2022. Softbound in undyed, hand-spun Kora cotton. Field recordings from the protest, 2020. Audio, 8 minutes 21 seconds. The Constitution of India. My father’s copy, gifted to him by his father on the day he joined the Civil Services, 2020. Inkjet print on paper.

More than one work on view ties the sectarianism that led to Partition to the massive demonstrations, often swelling to 150,000 people strong, that took place at Shaheen Bagh, a Muslim neighborhood in the Indian capital, in 2019–20. The protesters—largely women, from children to great-grandmothers—came out in support of students who had been violently suppressed for demonstrating against the Modi government. The catalyst for the outcry was the Citizenship (Amendment) Act, legislation that fast-tracks naturalization for refugees but pointedly excludes those of the Islamic faith, and related policy announcements that many believed could be used to strip citizenship from Muslims. Mumbai-based photographer Prarthna Singh’s clothbound photobook Har Shaam Shaheen Bagh. A record of the 100 day protest that took place in New Delhi from December 2019 to March 2020 (2022) is composed primarily of striking portraits of the women who risked their safety to defy an authoritarian government, along with transcriptions of their chants and songs, and other texts; it is accompanied by an audio piece—field recordings of the protest. Nearby, Singh’s The Constitution of India. My father’s copy, gifted to him by his father on the day he joined the Civil Services (2020) is a reminder of the distance India has traveled from the ideals of its democratic origins to today, and of the rights these hundreds of thousands of women were asserting—rights that Hindu nationalists have been working hard to take away from them.

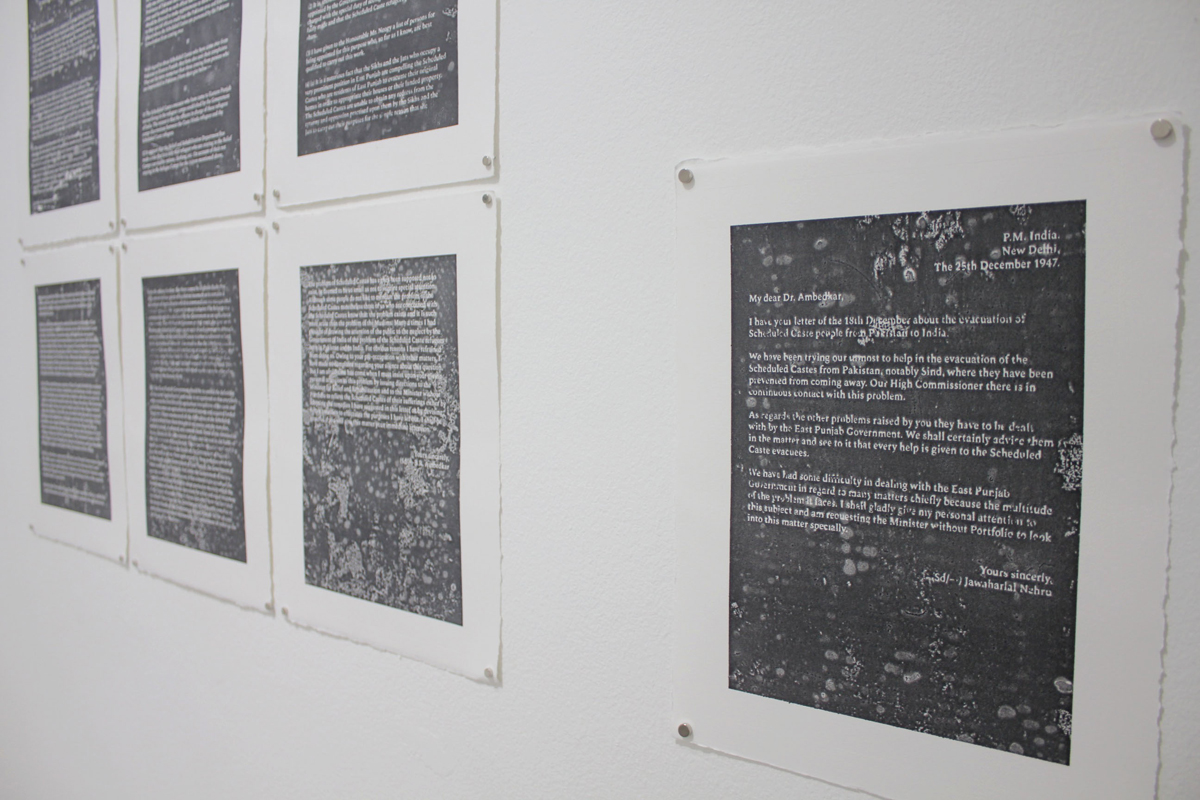

Proposals for a Memorial to Partition, installation view. Courtesy Twelve Gates Arts. Photo: Sahar Irshad. Pictured: Rajyashri Goody, Essential Services, 2003. Inkjet ink monotype on Arches paper.

India’s constitution was written by Dr. Bhimrao Ramji Ambedkar, a jurist, scholar, and reformer who sought the liberation of Dalits, a group that has for millennia been shackled to its place at the bottom of a social hierarchy. Rajyashri Goody’s Essential Services (2003) reproduces a series of letters between Ambedkar and India’s first Prime Minister, Jawaharlal Nehru, written months after the borders were drawn. In them, Ambedkar urges Nehru to intervene on behalf of Dalits who were being prevented from leaving what were now East and West Pakistan. The reason? Their dangerous and ill-paid work—as garbage pickers, as “sweepers” (cleaners of latrines and sewers), and other jobs in sanitation—had been declared “essential” by the new state authorities. (Those who did manage to get out were often denied entry to refugee camps because of their caste status.) The connection between the essential services provided by Dalits in 1947 and those provided by men and women in the US—largely racialized, mostly immigrants, often poor—during the pandemic is impossible to escape. Another of Goody’s pieces, Did you close the door? Or did you find it closed against you? (2023), installed above, likewise asks us to read the present through the past. The title phrase is rendered on the wall in excrement-colored clay slip; the artist paraphrases Ambedkar’s words as a question, asking all of us to consider our role in defining borders—geographical, social, racial, classist, or indeed casteist.

Proposals for a Memorial to Partition, installation view. Courtesy Twelve Gates Arts. Photo: Sahar Irshad. Pictured: Munem Wasif, from the series Spring Song, 2017–19. Archival pigment prints.

A number of works tie the refugee crisis of Partition to those happening today. One such example is Sreshta Rit Premnath’s Catch and Release (2023), an ethereal drawing made by sandwiching cotton rope, handwoven to resemble a chain-link fence, between two pieces of white paper. Another is Bangladeshi photographer Munem Wasif’s three photographs from a larger series titled Spring Song (2017–19). In the latter, humble objects, studio-lit to create crisp detail, are shot against vivid backgrounds: we see a beat-up bottle of skin lotion, a small toy house made of thin wood lath and string, a bundle of dried fish. The pictures wouldn’t be out of place in a magazine or on a billboard, though their status as commodities is iffy at best. Rather, they portray the possessions of a few of the millions of Rohingya people fleeing genocide in Myanmar who ended up in what is now the world’s largest refugee camp, in Bangladesh. Wasif’s choice to focus on signs of people’s determination to carve out a comforting ordinariness of daily life in the worst circumstances, rather than trotting out the usual pathetic images of people in distress, is gutting. The result is a quietly insistent reminder, one proffered by so many works in this exhibition, that we have not fully learned the lessons of 1947.

Aruna D’Souza is a writer and critic based in New York. She contributes to the New York Times and 4Columns, and is author of Whitewalling: Art, Race & Protest in 3 Acts (Badlands Unlimited, 2018). She is currently working on a new book, Seven Pictures for a New World, and a volume of collected essays.