Laura Adamczyk

Laura Adamczyk

In the author’s fourth novel, a medieval story of religiosity takes readers through a journey of filth.

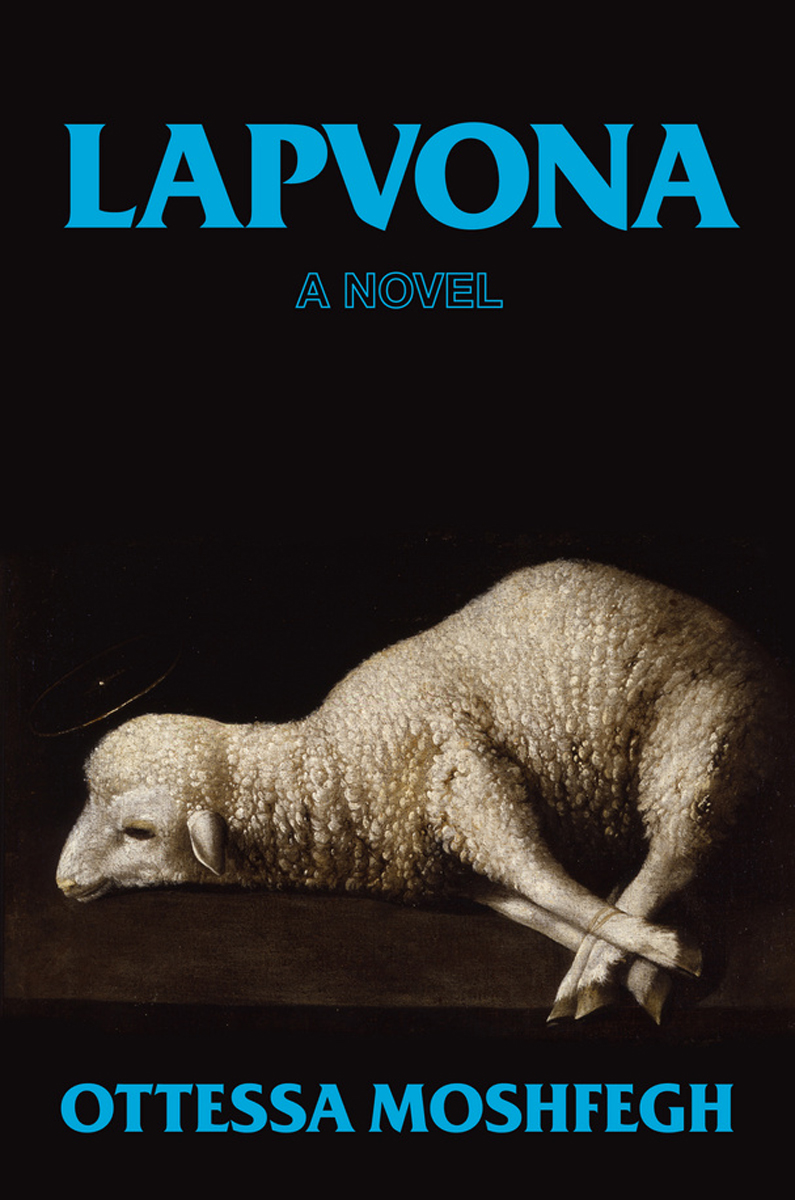

Lapvona, by Ottessa Moshfegh, Penguin Press, 304 pages, $27

• • •

It’s not the cannibalism that does it. When drought and famine befall Lapvona, the titular medieval town in Ottessa Moshfegh’s new novel, this brief lapse in the villagers’ vegetarianism serves to underscore the contrast between the ravaged hamlet and their lord’s palatial manor in the verdant hills above. What does do it—“it” being Moshfegh’s penchant for the grotesque finally tipping over into self-indulgence—is her rote accumulation of such details: bodily fluids, regurgitation, and, of course, shit. In one scene, the childish lord, Villiam, shoves his face against a servant girl’s backside to see how bad it smells before forcing his adopted son to rub a grape around his own asshole and make her eat it. The same servant, Lispeth, will imagine Villiam and the local priest eating each other’s excrement. Taken alone, such instances don’t call so much attention to themselves, but in their unfailing recurrence, Moshfegh’s fixation on filth starts to feel superfluous and silly. In earlier books like Homesick for Another World and Eileen, her portrayal of people’s ugliest, most disgusting proclivities was sharp and charged, integral to their characterization. Now, with the writer’s sixth book, it reads as a mindless compulsion, one that flattens her subjects rather than enlivening them.

Though Lapvona luxuriates in grotesquerie, one thing that differentiates it from Moshfegh’s previous works is its scope and plotting. Her first three novels were character studies, intense portraits of solitary women whose narratives, especially in Eileen and My Year of Rest and Relaxation, were an afterthought. Here, character and meaningful action work in concert; the cast is larger, and a lot more happens. What happens is this: the violent, tormented lamb herder Jude lives in Lapvona with his physically disabled teenage son, Marek, whose mother died in childbirth, a fact his father won’t let him forget. When a tragic accident occurs, Marek goes to live with Villiam in his lavish home, just before the drought makes a dusty graveyard of the land below. Jude struggles miserably to survive, as do the other villagers, including Ina, a reclusive hundred-year-old medicine woman. Ina served as wet nurse to Lapvona’s babies for decades, despite never having given birth herself, and continues to suckle the boys and men to comfort them and encourage favors in return. Throughout the catastrophic dry spell, Villiam’s estate remains lush and bountiful, as he’s diverted snowmelt to his reservoir rather than letting the water trickle down to the village.

Moshfegh has said she wrote Lapvona during COVID’s lockdown phase, and it’s hard not to find a parallel here: when disaster strikes—whether a pandemic or extreme weather caused by climate change—the rich will insulate themselves from its worst effects. Lapvona’s most powerful figures are callous, able to dispatch malicious orders with little care. Moshfegh is at her most animated, though, when depicting their buffoonery. Villiam’s pernicious acts are motivated less by malevolence than whim and a pathological need for constant stimulation. Aroused by humiliation—both others’ and his own—the dim-witted lord demands endless songs, dances, and jokes from his subordinates, the nastier the better. He sees his good fortune as evidence that he himself is good. Moshfegh makes a related critique of the impoverished villagers: the ruling class may be deceitful and dumb, but the oppressed are no better. The townspeople are broadly presented as naïve, petty, and bitter. Disinterested in stirring up trouble, they spite themselves by never questioning why Villiam’s life remains so comfortable and theirs so wretched.

In this, Moshfegh’s first full-length book in the third-person, her diction evinces a too-muchness akin to someone’s eyes gleaming while telling a gruesome story: guts “smacking” on a gallows floor. Babies “plunked out” rather than “birthed.” Even mundane actions get a lurid flourish. No one can just “eat” in this novel—everyone “slurps” or “gulps” or “sucks.” She also tends to explicitly spell out her characters’ motivations and the significance of their acts—narrating the way a child does when playing with their toys before an audience. Three-fourths into the novel, when Villiam tells the priest, Father Barnabas, that he loves him, Moshfegh writes, “It wasn’t quite love that Villiam felt, but an enduring trust and need for constant affirmation that was as good as love.” Which anyone who’s read up to that point would already know. Late in the novel, when an old man named Grigor confronts Villiam about stealing the water, Marek says to his adopted father, “ ‘Peasants . . . They think pride is a virtue. They haven’t learned yet that it is a vice.’ ” Never mind that Moshfegh hasn’t portrayed Marek as sharp enough to make even this simple statement; she’s stacked the deck so heavily in the sentiment’s favor—I think of Lispeth smugly eating just one cabbage leaf a day, believing her self-denial to be holy—to have any character say it aloud is overkill. Saturated with explanation, Lapvona leaves little room for the kind of ambiguity that might invite readers more fully into the story.

Moshfegh’s grander concerns, namely religion and its corruptions, are just as plagued by her heavy-handedness. The people of Lapvona use Christianity to suit their individual, often selfish purposes—to gain a social advantage, justify corporeal pleasure, or feel superior to their neighbors. Jude self-flagellates every week, ostensibly to atone, but relishes the pain. Marek is pious but cloying and duplicitous, trying to find shortcuts to currying God’s (and everyone else’s) favor. (He’s happy when Jude beats him, in part because he thinks it’ll make God pity him.) Father Barnabas, who scarcely knows even the most basic Bible stories, uses his status as priest to enjoy a life of comfort in Villiam’s manor and collect secrets from the villagers, like a medieval HR rep. This isn’t to say that Lapvona’s inhabitants aren’t believers. Rather, it’s that religion, instead of enriching people’s lives, destabilizes them. The only characters who find peace by novel’s end are those who develop a deeper, more meaningful relationship with God, albeit one loosened from the strictures of scripture and instead tied to the bounties of the natural world (they smoke weed).

Given the principal themes of the story, when Moshfegh wrote it, and especially her characterization of Villiam, one may catch glimpses of Trump throughout Lapvona. I was reminded in particular of when he had Black Lives Matter protestors violently cleared from DC’s Lafayette Square in the summer of 2020 so he could secure a stiff, self-serious photo of himself holding a Bible in front of St. John’s Church. Moshfegh portrays the way such false virtue is used as a blunt tool against others. As Barnabas tells his ignorant parishioners, “ ‘Chastise an evil-doer and God will know you’re good.’ ” This idea that religion is not a guiding light but a system that abets some of humanity’s worst impulses is not a particularly original one. It’s not improved by Moshfegh’s tack of shoving it in your face.

Laura Adamczyk is the author of the short story collection Hardly Children and the forthcoming novel Island City.