Rumaan Alam

Rumaan Alam

Nicolas Mathieu’s novel tracks life in a distressed French hamlet.

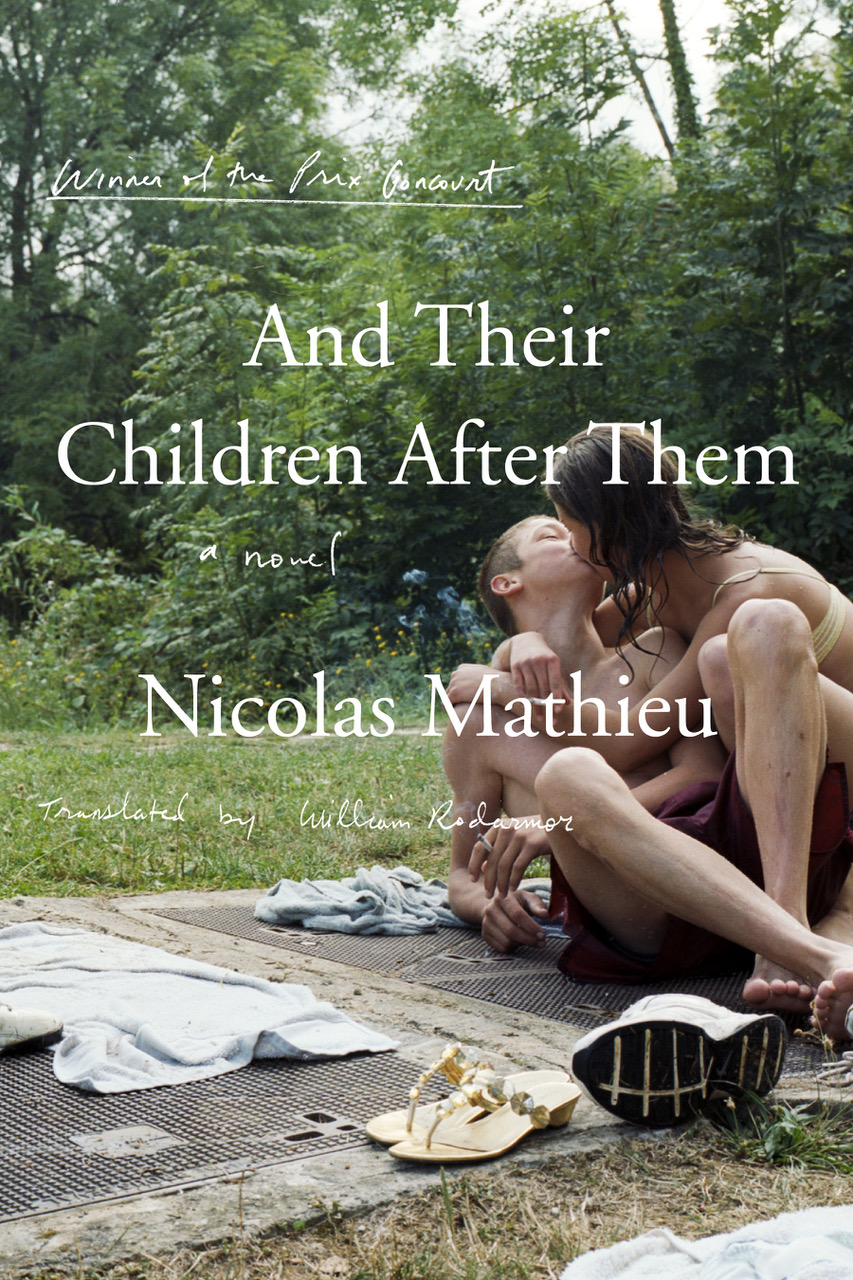

And Their Children After Them, by Nicolas Mathieu, translated by William Rodarmor, Other Press, 420 pages, $17.99

• • •

I expect to meet in a French novel the same sorts of people I meet in the American novel: folks fretting about divorce or death, authorial avatars stressing about the making of art or the meaning of life. OK, maybe they’re more chic—smoking cigarettes, sharply dressed—but they’re essentially the same. The contemporary novel, no matter its nation of origin, is truly a middle-class concern.

In previous eras, the novel was a popular enough form that its creators occupied a bully pulpit. But it’s been a long time since the moralizing fictions of Dickens could galvanize a society. A chicken-and-egg conundrum: Is the form’s diminished popularity to blame for the novel’s insularity, or a result of it? It’s out of fashion for the novel to show its readers how the other half lives, perhaps because that would be to admit that the novel generally is meant only for a certain reader.

That’s part of what’s surprising about And Their Children After Them, which won Nicolas Mathieu the Prix Goncourt in 2018 and is now available in English, in a translation by William Rodarmor. I think you could trace a line from Hard Times to this book; both acts of witness and critique. Dickens was talking Victorian-era life in a made-up mill town, while Mathieu is interested in the people of contemporary exurban France, a valley hamlet called Heillange:

The men said little and died young. The women dyed their hair and looked at life with gradually fading optimism. When they got old, they retained the memory of their men, beaten down on the job, at bars or sick with silicosis, and their sons dead in car crashes, not counting the ones who packed up and left.

I don’t know if the people herein—manual laborers, striving immigrants, lower-middle-class professionals, and the children of all of them, poorly served by a state that doesn’t care about people like them—are invisible in French politics, media, or literature. In this country, we certainly meet them more in newspapers (the profiles of Trump voters we’ve been reading since 2015) than in novels.

It’s not exactly cheerful. Perhaps understanding this, Mathieu gives us the compensatory thrill of sex. Or maybe that’s just because he’s French. The book opens in 1992, with Anthony, who’s just turned fourteen: “The urge to see girls’ bodies was overwhelming and constant. He kept magazines and videotapes in his drawers and under his bed, not to mention tissues. His pals at school were all the same way, totally obsessed. It was making them crazy.”

Anthony is one of a large cast—his cousin (who remains curiously unnamed), his parents, a girl he’s interested in, a local tough with whom he gets entangled (and that kid’s immigrant dad). It’s all easier to keep track of than it sounds in summary, maybe because Mathieu is an adept writer, or maybe because it formally resembles a television drama, cutting from one storyline to the next. The author even mentions Beverly Hills, 90210 (it’s the nineties), but And Their Children is distinctly an HBO affair, if for no other reason than its relentless horniness. It’s not just the teens; Anthony’s mom gets lucky too: “he fucked her while she was kneeling on the rug. Hélène had no problem with the concept, but changed her mind later, when she saw the carpet burns on her knees.”

Like many a prestige television show, the novel is enjoyable, sometimes addictive, occasionally ridiculous. In the first section, Anthony, idiot teen that he is, commandeers his dad’s motorbike to sneak out to a party. It’s stolen, naturally. The culprit is Hacine, the son of Moroccan parents. To reckon with stereotype is to juggle with knives, and Mathieu doesn’t emerge unscarred. Hacine’s trajectory from local hoodlum to worse (spoiler averted) is not imaginative, but perhaps that is the intention, to conjure the few options for first-generation immigrants in France. I should note that by the book’s end, Hacine is given the most surprising and lovely near-redemption.

I’ll belabor the metaphor. Like many a prestige television show, the novel is at its best at the outset—idiosyncratic, irresistible, atmospheric. The second section (I almost said “season”) offers a satisfying advancement on the first, visiting the characters a couple of years on. By its third section, though, the text’s desire to say something important becomes too urgent. The author chooses a device that challenges credulity—all the characters gather for Bastille Day fireworks—to make a statement not about his players but the place:

For some time now, downtown Heillange was being pulled in different directions. Businesses were heading out to the periphery while the historic core, with its streets and buildings, was being renovated at great expense. The mayor was ambitious, and he had accommodating bankers. There were practically no factories left in the valley, and young people were leaving for lack of jobs.

American readers will recognize in this the preamble familiar from all those aforementioned profiles of Trump voters. Unlike so many of our journalists, Mathieu does not shy from the difficult stuff. Here’s a minor character’s xenophobia: “The real problem was the influx of immigrants. You could just do the math. The number of immigrants, about three million, exactly matched the number of the unemployed. Hell of a coincidence, right?” It’s not easy to animate these social messages; the novel that aspires to always risks collapse, like a too-heavy cake.

Mathieu is better at creating people than making political points. The former is much harder, and what we want of our novelists anyway. Consider Hélène’s fate, sketched out in a few efficient lines: “She was forgotten. She kept boxes of cookies, candies, and peanuts in a locked drawer, and nibbled. She gained twenty-five pounds.” She’s a small presence in this book, but I was moved to read of her quiet despair in an office park.

As the novel draws down, the writer strains to deliver a moral: capitalism is destructive, globalization frightening, poverty immoral, and a life of conventional domesticity almost unavoidable. I accept those lessons, even if I was irritated by some of the novel’s more cinematic flourishes. As it opened with the theft of a motorbike, you can guess it will conclude with another motorbike, another theft. That said: I’m someone who’s (unfailingly!) tearful at a television show’s finale—Dorothy abandoning the rest of the golden girls; that awful Sia song and everyone from Six Feet Under dying. A little silly, sure, but sometimes it’s a comfort to let go, to let art transport us.

Rumaan Alam is the author of the novels Rich and Pretty and That Kind of Mother; his novel Leave the World Behind will be published in October.