Melissa Anderson

Melissa Anderson

In a 1945 noir, Gene Tierney dives deep into derangement.

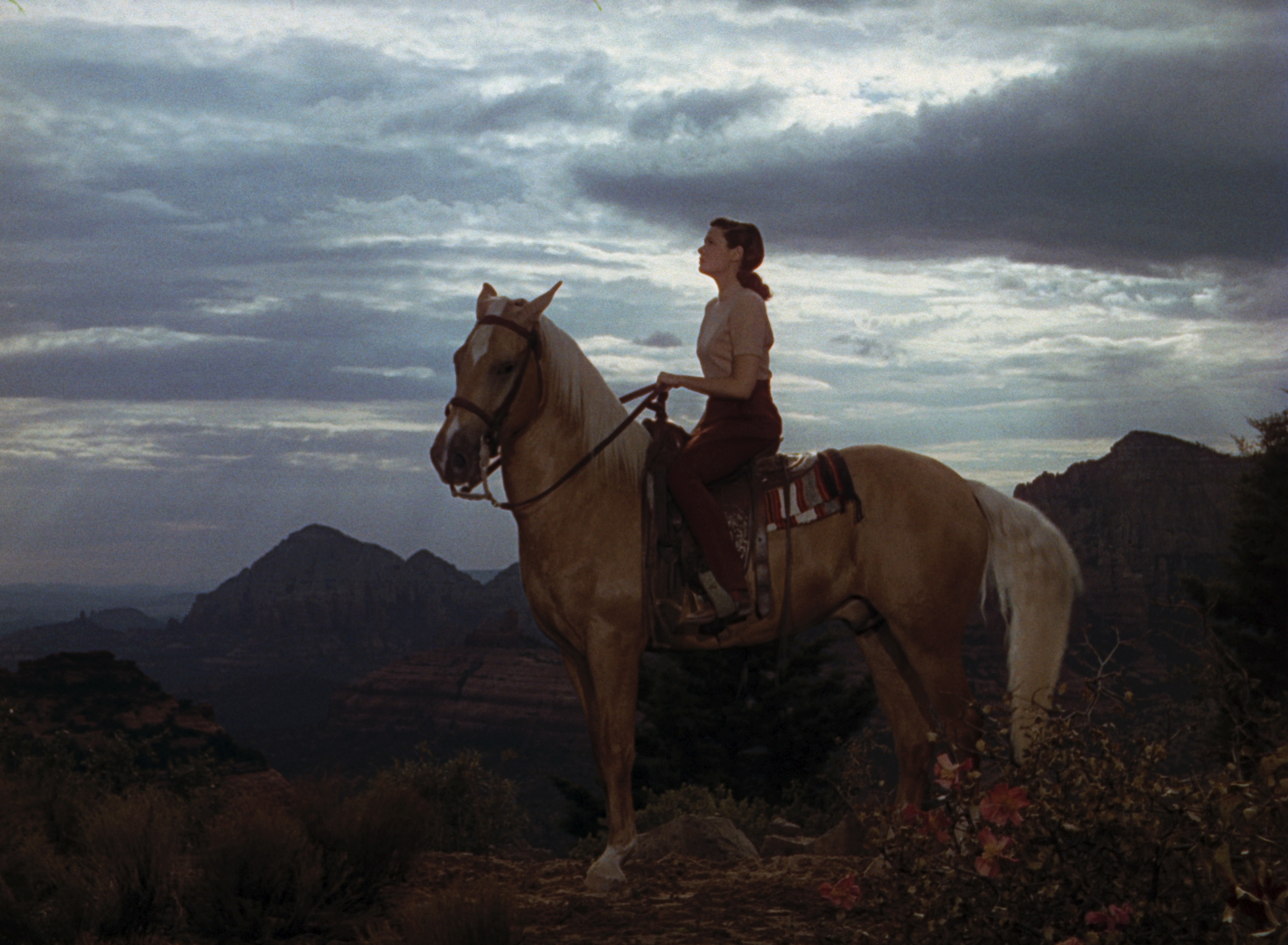

Gene Tierney as Ellen Berent in Leave Her to Heaven. Image courtesy Criterion Collection.

Leave Her to Heaven, directed by John M. Stahl, available on Blu-ray and DVD from the Criterion Collection

• • •

A lurid tale of toxic femininity and of marital bliss curdled into conjugal horror, John M. Stahl’s Leave Her to Heaven ranks as one of the great outliers of classic film noir, at least formally. This 1945 movie was filmed in lambent Technicolor and takes place primarily in wide-open, sun-filled spaces in New Mexico and Maine, elements at odds with a genre so often associated with stark black-and-white cinematography and foreboding metropolises. But its central character, Ellen Berent, played with blood-freezing patrician precision by Gene Tierney, exceeds the malice of even Double Indemnity’s Phyllis Dietrichson, perhaps the paradigmatic noir seductress. Ellen is more than a femme fatale: she is an unparalleled psychopath.

Based on Ben Ames Williams’s bestselling 1944 novel of the same name, Leave Her to Heaven takes its title from a line in the first act of Hamlet: the Ghost exhorts the Prince of Denmark not to seek vengeance against Queen Gertrude but instead to “leave her to heaven, and to those thorns that in her bosom lodge to prick and sting her.” (Stahl’s movie was the second of two Tierney-starring vehicles to namecheck nirvana, following Ernst Lubitsch’s 1943 comedy, Heaven Can Wait.) Ellen’s empyrean beauty dazzles Richard Harland (Cornel Wilde), a novelist who is instantly enchanted with the soigné woman sitting across from him in the club car of a New Mexico–bound train—and not only because she happens to be reading one of his books. He’s beguiled, yes, but also a little unnerved. Ellen gazes at him—every shimmer of Tierney’s sea-green eyes, every fold in her lilac sheath dress impeccably lensed by cinematographer Leon Shamroy—for an uncomfortably long time before she delivers this perverse pickup line: “I was staring at you, wasn’t I? I didn’t mean to, really. It’s only because . . . because you look so much like my father. When he was younger, of course, your age. A most remarkable resemblance.”

Cornel Wilde as Richard Harland and Gene Tierney as Ellen Berent in Leave Her to Heaven. Image courtesy Criterion Collection.

The serendipities continue. It turns out that Richard and Ellen—along with her mother (Mary Philips) and sister, Ruth (Jeanne Crain)—are guests at the Taos ranch house of a mutual friend, lawyer Glen Robie (Ray Collins), the narrator of Leave Her to Heaven, which unfolds, as most noirs do, in flashback. Ellen and her family are in the southwest to scatter the ashes of dearly departed Dad. “We were inseparable,” Ellen tells Richard about her pops, with a mite too much alacrity. Her zeal repeats just a day or two after this ceremonial rite when she proposes marriage to the besotted writer, with this promise—or threat: “I’ll never let you go. Never, never, never.”

From here, Leave Her to Heaven plunges us deeper into derangement, as Ellen becomes a maniacal helpmeet. Insisting that she wants to do and be everything for her spouse and ruled by diabolical jealousy, this picture-perfect wife inexorably alienates Richard from all those he loves. She conducts her campaign stealthily at first; many of the film’s sick thrills are rooted in Tierney’s superior talent for dissimulation. In an early instance of her attempt to prove unwavering uxorial devotion, Ellen suggests that she and Richard, immediately post-honeymoon, set up house temporarily next to the rehabilitation center in Georgia where his adored, physically disabled teenage brother, Danny (Darryl Hickman), is a resident. She’s excessively solicitous of the kid, but during a private conversation with Danny’s doctor, who insists the boy is now well enough to live with the couple at Richard’s lake hideaway in Maine, Ellen’s veneer cracks: “But after all, he’s a cripple!”

Gene Tierney as Ellen Berent and Cornel Wilde as Richard Harland in Leave Her to Heaven. Image courtesy Criterion Collection.

Once the trio is installed in this bucolic lair—with Danny’s bedroom just on the other side of the newlyweds’—Ellen’s ability to mask her corroded mind falters. She pouts and rages at anything that takes Richard’s attention away from her, whether his work (“I hate your chapters! I hate all your chapters!”), his beloved sibling, or her visiting relatives. Richard, slowly realizing that his missus is unhinged, turns to his mother-in-law for advice. Mama Berent’s cold comfort—“There’s nothing wrong with Ellen. It’s just that she loves too much”—reveals the delusions of a parent long suffering from Stockholm syndrome, worn down by the emotional terrorism of her daughter. How much does Ellen love Richard? So much so that she imperturbably watches—behind sunglasses, in a ghoulish echo of the stare that she had affixed on Richard in the train—Danny drown while she sits in a canoe no more than a yard away from the flailing boy.

Gene Tierney as Ellen Berent in Leave Her to Heaven. Image courtesy Criterion Collection.

Stahl, who had established himself as a director of melodramas with Imitation of Life (1934) and Magnificent Obsession (1935)—monochrome “women’s pictures” that would be remade in florid color by Douglas Sirk two decades later—slyly suggests that domesticity itself, taken to its extreme, poses the greatest menace. Ellen, determined to nest only with her husband, finds ways to weaponize the most mundane household objects to reach her grisly goals: following close-ups of a pair of low-heeled mules and a slightly loosened carpet, Ellen “trips,” her fall down a flight of stairs a means to terminate “the little beast” growing inside her.

Gene Tierney as Ellen Berent in Leave Her to Heaven. Image courtesy Criterion Collection.

Tierney was nominated for a Best Actress Oscar for Leave Her to Heaven, among the highest-grossing films of 1945. She lost to Joan Crawford, playing a very different kind of noir protagonist—a noble, self-abnegating mother—in Mildred Pierce, a role greatly at odds with Crawford’s own sadistic parenting style, per Mommie Dearest, her daughter Christina’s scandalous tell-all book from 1978. That memoir, with its scabrous stories of the “real” Crawford, did much to color subsequent perceptions of the actress’s performances. Similarly, it’s impossible for me to watch Leave Her to Heaven (or any Tierney movie) without thinking about the mental illnesses that would begin to plague her roughly a decade after Stahl’s film and would persist until her death, in 1991. Onscreen, Tierney gave us a chilling portrait of an elegant lunatic. Offscreen, she endured multiple hospitalizations and electric-shock therapy (and more and worse), detailing her anguish in her 1979 autobiography, Self-Portrait. I wonder whether Tierney ever considered the title Leave Her to Hell.

Melissa Anderson is the film editor of 4Columns.