Rumaan Alam

Rumaan Alam

Writing as necessity: Lily King’s novel follows a young author.

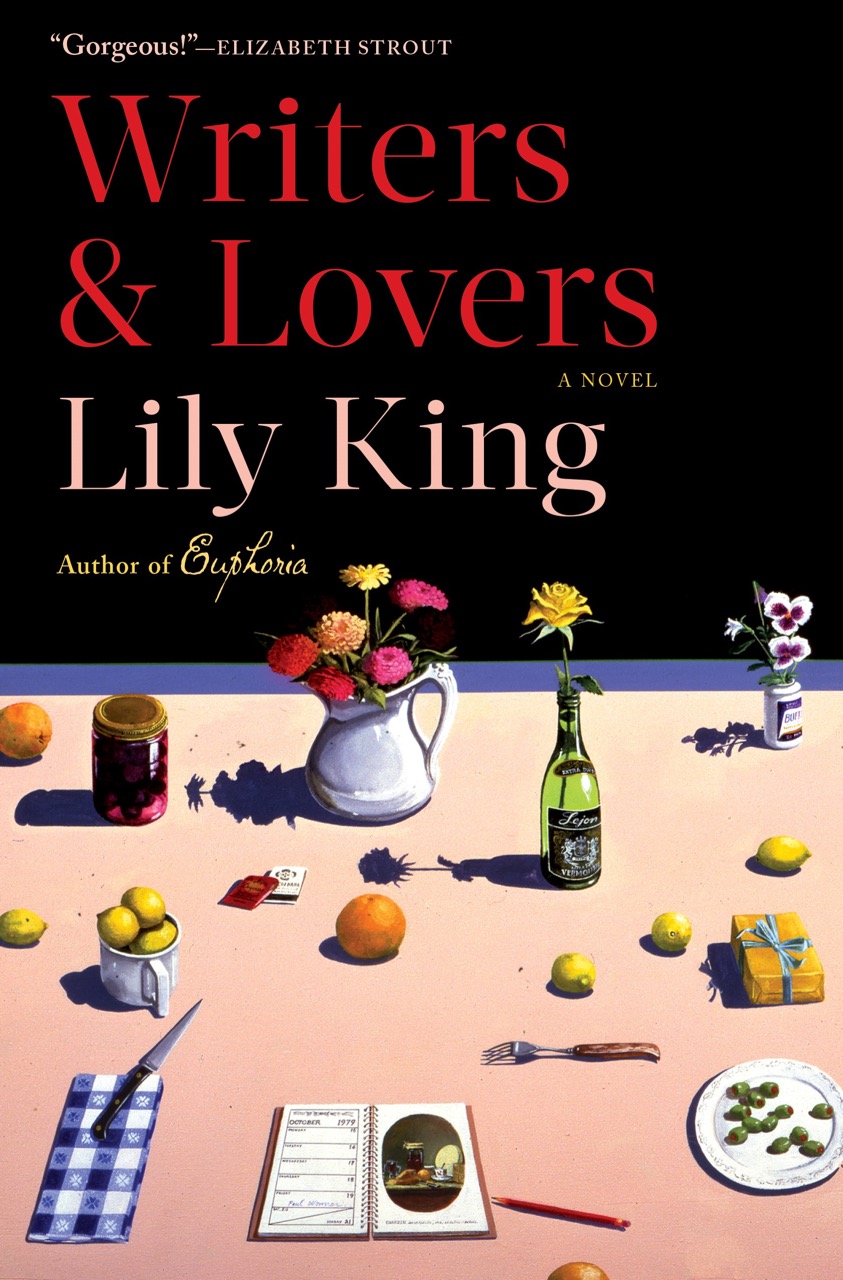

Writers & Lovers, by Lily King, Grove Press, 324 pages, $27

• • •

There is something familiar but somehow off-kilter about Writers & Lovers, Lily King’s fifth novel, like a beloved sitcom dubbed into another tongue. The narrator is eking out a living, alienated from family, and consistently unlucky in love. But solitude and life’s material privations are simply the cost of belief in one’s art—in this case, as the title indicates, in writing. We’ve heard versions of this story from Thomas Wolfe, Philip Roth, Saul Bellow, Paul Auster, Ernest Hemingway.

The bildungsroman traces the arc of childhood into maturity, so maybe it’s a misnomer for a text about artistic development, which is independent of age. Still, we’ve met the novel of the would-be novelist before: the heartbreak, the frustration, the rejection, the isolation, the sex (plenty of that, on the page if not in life), the consolation of or possibly condemnation to the work. But King challenges convention by giving us a portrait of the artist as a young woman.

That woman, Casey, is in a sorry state, mourning the sudden and inexplicable death of her mother, avoiding the reality of her student loan debt, and bouncing from one subpar lover to the next. But she does not quite feel sorry for herself. She’s arranged her life on terms that allow her to devote time to her art. She doesn’t posit this as a heroic calling, but a necessity. “I don’t write because I think I have something to say. I write because if I don’t, everything feels even worse.”

Writers & Lovers is set in Boston in 1997, which (disturbingly) probably means it qualifies as historical fiction; the author is so adept at conjuring the machinations of restaurant life it might also be thought of as a workplace novel. But at heart, it is another, rarer sort of book. Our great women writers have been up to a lot—the social novel or the satire and everything in between—but they’ve been less drawn to what their male peers seem never to get enough of: the subject of their own authorship.

King uses romance as a plot, but the real love here is art. Early in the novel, Casey and a friend leave a party and walk home. “We talk about a book called Troubles that I read and passed along to her. She loved it as much as I did, and we go through the scenes we liked best. It’s a particular kind of pleasure, of intimacy, loving a book with someone.”

You wish for Casey this delight with a man, but the men—there are quite a few—all come up short. Perhaps she ought to date someone who’s not also a writer! There’s Luke, a poet with whom she has a passionate affair while at an artist’s colony; Silas, a writer she meets through a friend; and Oscar, a well-known novelist, a widower with two young children. King is very good at transporting us back to the frustrations of youthful romance; who wouldn’t choose art over this:

Silas leaves me a message, then another, and I don’t call back. I’ve made my choice. I’m done with the seesaw, the hot and cold, the guys who don’t know or can’t tell you what they want. I’m done with kissing that melts your bones followed by ten days of silence followed by a fucking pat on the arm at the T stop.

Gen X readers will thrill to Writers & Lovers’ depiction of postgraduate ennui in the 1990s; younger readers will appreciate how the book inverts the strategy of Adelle Waldman’s The Love Affairs of Nathaniel P., letting Casey be the self-centered (or self-respecting) artist. But she is only human.

Her relationship with Oscar occupies most of the book. They’re part of the same orbit, but truly meet cute—it’s a contrivance, but not a bad one—when he and his sons dine at the restaurant where she’s a server. How a writer handles children is a metric of something, and King balances the adorably sentimental with the less-so: “Anything can catch fire. Being around kids means thinking a whole lot of things you can’t say.”

The romance between the young striver and the celebrated novelist would seem to embody the choice between love and art. I wish the book had probed more deeply the fact that Casey has a profoundly broken relationship with her father (daddy issues, as they say), the reverberations of a long-ago transgression that I don’t want to spoil. I’ll say only that I sighed in relief when Casey says of her boyfriend, “I should have wanted to be him, not sleep with him.”

This is a book unabashedly full of feeling—a daughter’s grief for her mother, a woman’s yearning to love someone worth it, an artist’s worry that her faith might be delusion. There’s a sense of autobiography: writing matters deeply to Casey, and presumably to King, and certainly many writers will love this book for seeing themselves reflected in it. But the author gives us something more universal, too: I could not help but recall my own youth and its ambitions and heartbreaks, its paths not taken and pitfalls avoided.

Writers & Lovers has an almost deliriously happy ending. The story’s conclusion is recompense not only for what Casey endures—it’s a salve for us, the reader, the follies of our own younger selves. It’s a reminder that happiness, love, and artistic fulfillment are not too much to ask, that if having it all is a myth, you can still demand a whole hell of a lot. Yes, this is only a story, but you must admit, that is not a bad moral.

Rumaan Alam is the author of the novels Rich and Pretty and That Kind of Mother; his novel Leave the World Behind will be published in October.