Leo Goldsmith

Leo Goldsmith

In a near-future film, a Brazilian town fights erasure.

Bacurau. Image courtesy Kino Lorber.

Bacurau, directed by Kleber Mendonça Filho and Juliano Dornelles, now playing in New York City

• • •

Popular art and politics always seem to collide in awkward ways, especially in the cinema. Indeed, we seem to be living in particularly interesting times when Parasite, a South Korean anti-capitalist fable, is received by Hollywood’s elite with its top award—oblivious to the contradiction therein.

Kleber Mendonça Filho and Juliano Dornelles’s Bacurau arrives in American cinemas amid this atmosphere of incongruity. A tropical Mad Max, a western for the underdeveloped world (a “global southern”?), a (relatively) big-budget anti-colonialist grindhouse, Bacurau belongs to that category of near-future speculative fiction that has much more to say about the present than about the future (or one can hope). Its jaundiced vision of contemporary Brazil’s hotly divisive racial politics and economic exploitation isn’t prescient, but all-too-familiar.

While the film was many years in the making, it nonetheless debuted at a moment that was almost perversely apt, premiering at Cannes last May on the heels of the neofascist Jair Bolsonaro’s election as Brazil’s president. As if eager to confirm this, the Brazilian government added to the Cannes festivities by publicizing an earlier demand that codirector Mendonça pay back the equivalent of roughly half a million dollars of state funding for his 2012 breakout film, Neighboring Sounds, which it claimed had been misallocated. (The case is still in limbo.) Thus, the filmmakers find themselves at war with villains that closely resemble those in their own movie.

Bacurau. Image courtesy Kino Lorber. Photo: Victor Jucá.

Bacurau begins, ominously enough, with a cosmic introduction that descends, Google Earth–style, from the planet’s upper atmosphere to a highway littered with empty coffins, a locale vaguely situated in, a title card tells us, “Western Pernambuco, a few years from now.” Here we find the fictional town of the title, a sleepy and seemingly innocuous village where people appear mostly to spend their time hanging out, having sex, and popping obscure psychedelics, and the official motto is “If you go, go in peace.” We enter the scene alongside Teresa (Bárbara Colen), a young doctor who returns to Bacurau from a run for important medical supplies to attend the funeral of her grandmother Carmelita, the ninety-four-year-old matriarch whose influence still haunts the dusty backwater. During the ceremony, we meet the town’s populace, a lively assortment of aging hippies and DJs, queers and balladeers, nudists and sex workers, and internet-famous contract killers on the lam. (Sônia Braga, the famed Brazilian-American actress who starred in Mendonça’s 2016 film, Aquarius, appears here as a tetchy lesbian doctor and reluctant materfamilias.) Bacurau, in short, seems like a full realization of Brazil’s cultural syncretism—colorful, warm, and brimming with music, culture, and party drugs.

Sônia Braga as Domingas (center) in Bacurau. Image courtesy Kino Lorber. Photo: Victor Jucá.

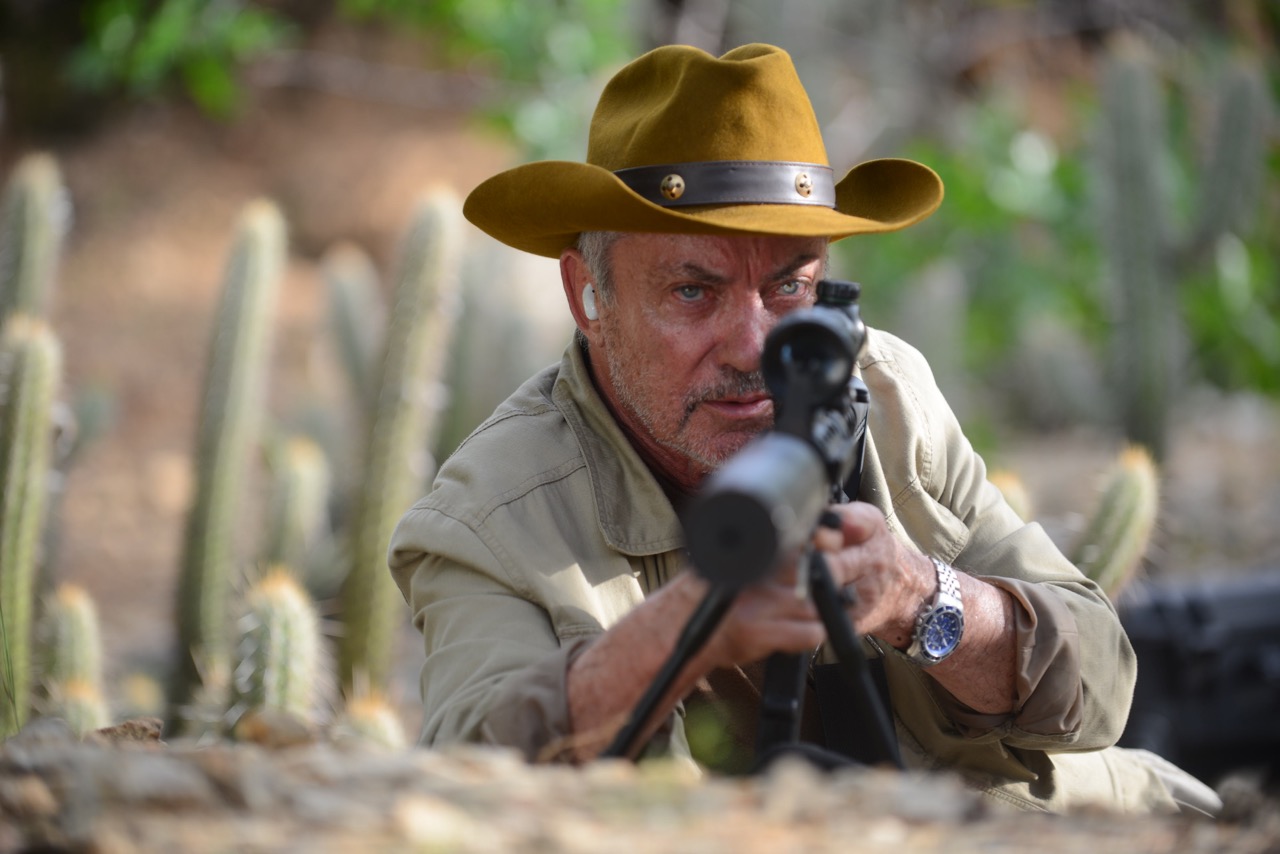

It’s also very much off-the-grid—disconnected from the water supply by renegade armed cadres who seem to be in cahoots with the corrupt local government. By the film’s midpoint, the townspeople discover that Bacurau is now suddenly nowhere to be found on Google Maps and ominously lacking a cellphone signal. All of this, it turns out, is part of a wider, and quite familiar, plot of erasure, rendering the town’s inhabitants, their history, their very claim to existence in Brazil, literally invisible. As the Bacurauans emphasize, they are northern Brazilians, which is to say largely Indigenous, Black, or most likely a hybrid of all of the above. This point is made abundantly clear when two ultra-neon-clad motorcyclists show up from the South in the film’s second act, their arrival an omen as unwelcome as the UFO-shaped drone seen floating around the outlying areas. When some of the locals begin to turn up dead, we find that this apparent pair of white, joy-riding tourists are actually fixers for a Euro-American band of white supremacist paramilitaries, made up of supermarket middle managers, would-be mass shooters, and shallow thrill seekers, led by—why not?—Udo Kier.

Udo Kier as Michael in Bacurau. Image courtesy Kino Lorber.

The film thus sets the stage for a plot straight out of a spaghetti western, in which the scrappy villagers, with help from some friendly local bandits and their own homegrown traditions of counter-colonialism, seek to fend off the encroaching outsiders. And, fittingly, Mendonça and Dornelles embellish their tale with all manner of ’70s and ’80s genre flourishes: epic Cinemascope framing; Star Wars–like wipe transitions between scenes; dramatic split diopter shots, which keep extreme foreground and background in focus in a single, dynamic composition; the occasional splatter of an exploding head. The soundtrack even boasts a synth anthem by John Carpenter, whose name appears—lusophonized as “João Carpinteiro”—over the door of the local school in dorky tribute. In this way, while the movie recalls—as any Brazilian political film is wont to do—Glauber Rocha’s Terra em transe (1967), also an allegory of contemporary political corruption, exploitation, and struggle, or the more recent super-low-budget steampunk dystopias of Adirley Queirós, Bacurau looks and feels more like a Hollywood production. Where Rocha’s Cinema Novo classic is formally jagged and pure agitprop, and Queirós’s work provides an exemplar of DIY sci-fi, Bacurau opts instead for commercial polish, with CGI, a lurid orange-blue palette (replicated in the movie’s Drew Struzan–esque poster), and an elaborate camera movement in practically every shot.

Silvero Pereira as Lunga in Bacurau. Image courtesy Kino Lorber.

Dressing up radical politics in pop forms is, of course, nothing new. Indeed, as film scholar Robert Stam has argued, this is part of a long history of appropriation in Brazilian aesthetics, in which the artistic forms of the colonizer are ingested by local artists to create new hybrids: a kind of cultural cannibalism.

Still, it’s always jarring for a non-Brazilian to see a putatively leftist film emblazoned with the logo of Petrobras, Brazil’s semipublic oil company, which also—until Bolsonaro—provided much of the nation’s arts funding. Under the new regime, Brazilian artists—at least the ones on the left—are unlikely to see a centavo of this money. Meanwhile, the new president has opened up the country’s oil reserves to larger multinational petrochemical companies with no intention so benevolent as money for art or education. Petrobras’s arts funding may have been a deal with the devil for Brazilian artists, but at least it was their devil. In this way, Bacurau may inadvertently prove to be a turning point in Brazilian cinema, one that demands new forms and new strategies for political filmmaking—or one that deepens the contradictions.

Leo Goldsmith is a writer, teacher, and curator based in Brooklyn. He writes about art and film for such publications as Artforum, art-agenda, the Brooklyn Rail, and Cinema Scope.