Johanna Fateman

Johanna Fateman

From iPhones to a mythic monkey kingdom: a show of paintings from the browser cache.

Leidy Churchman: Earth Bound, installation view. © Leidy Churchman. Image courtesy Matthew Marks Gallery. Photo: Aaron Wax. Pictured, left to right: Reclining Buddha and Kishkindha Forest (Jodhpur).

Leidy Churchman: Earth Bound, Matthew Marks Gallery, 522 West Twenty-Second Street, New York City, through April 18, 2020

• • •

My Kindle Cloud Reader displays a two-page spread from the 2008 book True Perception: The Path of Dharma Art by Chögyam Trungpa Rinpoche, the Tibetan scholar and meditation master who introduced Vajrayana Buddhism to the West. Another window shows a 2016 post on the Whitney Museum’s Education Blog titled “Teens Meet Leidy Churchman,” which tells of the artist reading passages of Trungpa’s book to a group of students, and meditating with them. I have, in other tabs, the press release for Churchman’s new exhibition, Earth Bound; a Twitter search for #coronavirus; a “quick shop” view of a jacket, which, now marked down, still costs too much; and various Wikipedia pages, including the one for “Reclining Buddha,” where I found the source image for Churchman’s 2020 painting of the same name.

Leidy Churchman, Reclining Buddha, 2020. Oil on linen in niche designed by the artist, 48 × 79 inches. © Leidy Churchman. Image courtesy Matthew Marks Gallery. Photo: Aaron Wax.

Among the characteristically cryptic assortment of twenty-one canvases on view at Matthew Marks, Reclining Buddha is the only one that’s not installed on a white wall. Placed in a pale blue, shrine-shaped niche designed by the artist, it faithfully reproduces the Wikipedia photo’s generous vantage, showing the length of the monumental, stone-carved side-sleeping figure, which belongs to the twelfth-century Gal Vihara temple in Polonnaruwa, Sri Lanka. A crumbling, low brick wall partially cordons the statue off; a simple bench avails itself to tired or contemplative visitors; and the composition’s postcard-like white border subtly signals that it’s not a plein-air portrait—all somewhat humbling features, at odds, maybe, with its devotional framing.

“The term dharma art does not mean art depicting Buddhist symbols or ideas, such as the wheel of life or the story of Gautama Buddha,” writes Trungpa, not with regard to Churchman’s scene, of course, but for the occasion of the first-ever session of the Naropa Institute, in 1974. (His missive is included in the aforementioned posthumous collection, True Perception). “Rather, dharma art refers to art that springs from a certain state of mind on the part of the artist that could be called the meditative state,” he continues. “It is an attitude of directness and unself-consciousness in one’s creative work.” The use of the Buddha—in the piece cited above, and in related, scattered references elsewhere—orients us to the philosophical concerns of Churchman’s art. But the assiduous painter, who mostly forgoes oil’s capacity for seduction, doesn’t glorify or even particularly highlight such symbols’ metaphysical significance. Instead, Churchman emphasizes their impermanent, un-iconographic existence as things in the world and on the internet.

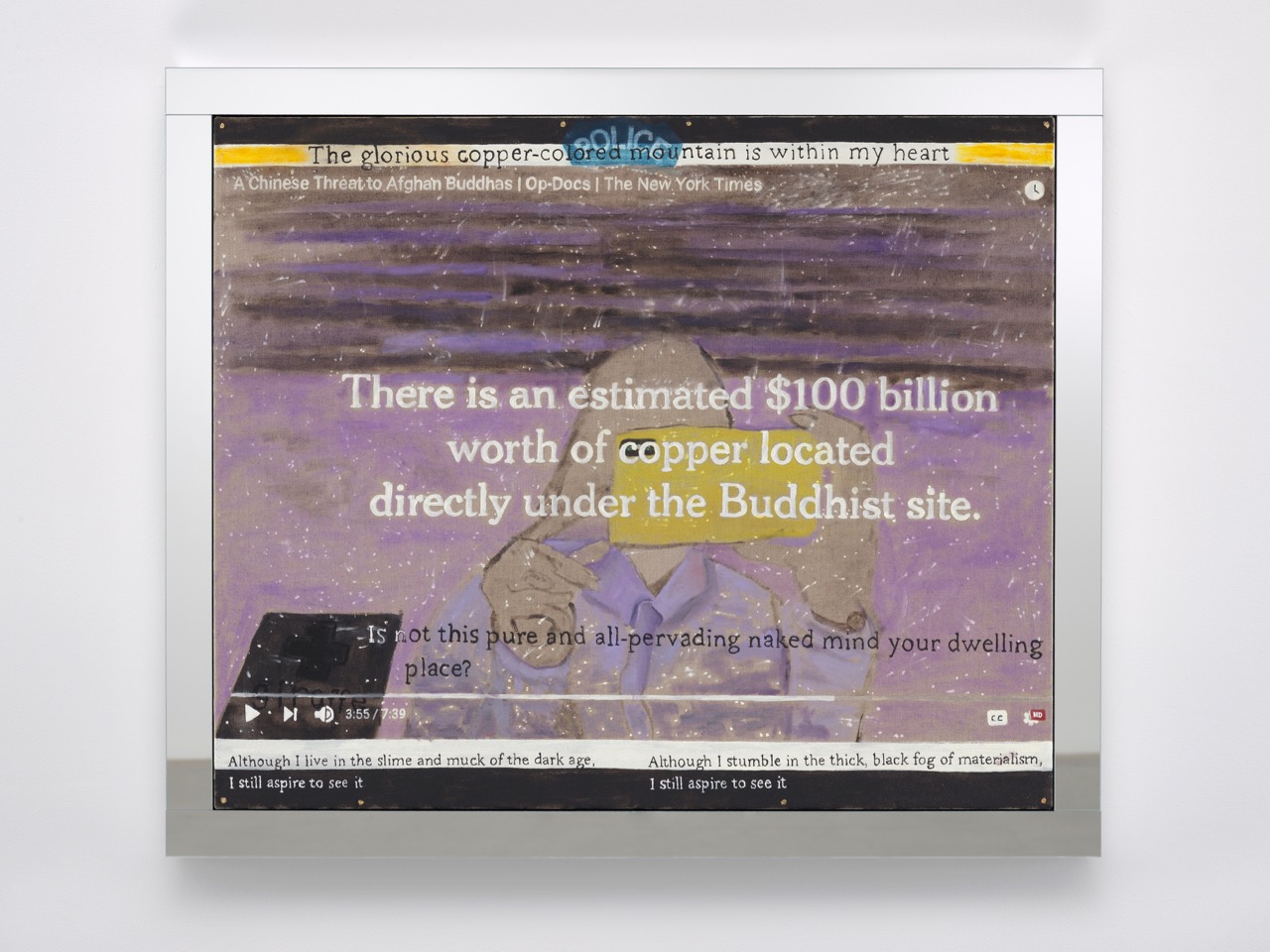

Leidy Churchman, 100 Billion Sadhana of Mahamudra, 2020. Oil on linen, mirror, 32 1/8 × 38 inches. © Leidy Churchman. Image courtesy Matthew Marks Gallery. Photo: Aaron Wax.

The hazy, purple and gold 100 Billion Sadhana of Mahamudra (2020) shows what seems to be a screengrab of a paused video on YouTube. In fact, we are looking at an ominous, dreamy composite: a still from a Times “op-doc” titled “A Chinese Threat to Afghan Buddhas,” which reports on the threat to Buddhist antiquities (from a Chinese mining company as well as the Taliban), is overlaid with an iPhone-holding figure and lines of text. It’s Trungpa again: “Although I stumble in the thick, black fog of materialism / I still aspire to see it.” (“It,” in the original text, part of a shifting refrain, refers to “the all-pervading naked mind,” among other related, poetic possibilities.) The layered painting is a despairing comment on global-capitalist rapacity and war. It also captures the particular kind of synthesis—and confusion—born of the easy and endless juxtapositions that the web affords. And it might recall, if you’ve ever sought meditation instruction, one of anxious thinking’s rapid crossfades that becomes particularly vivid as you try to let thinking go.

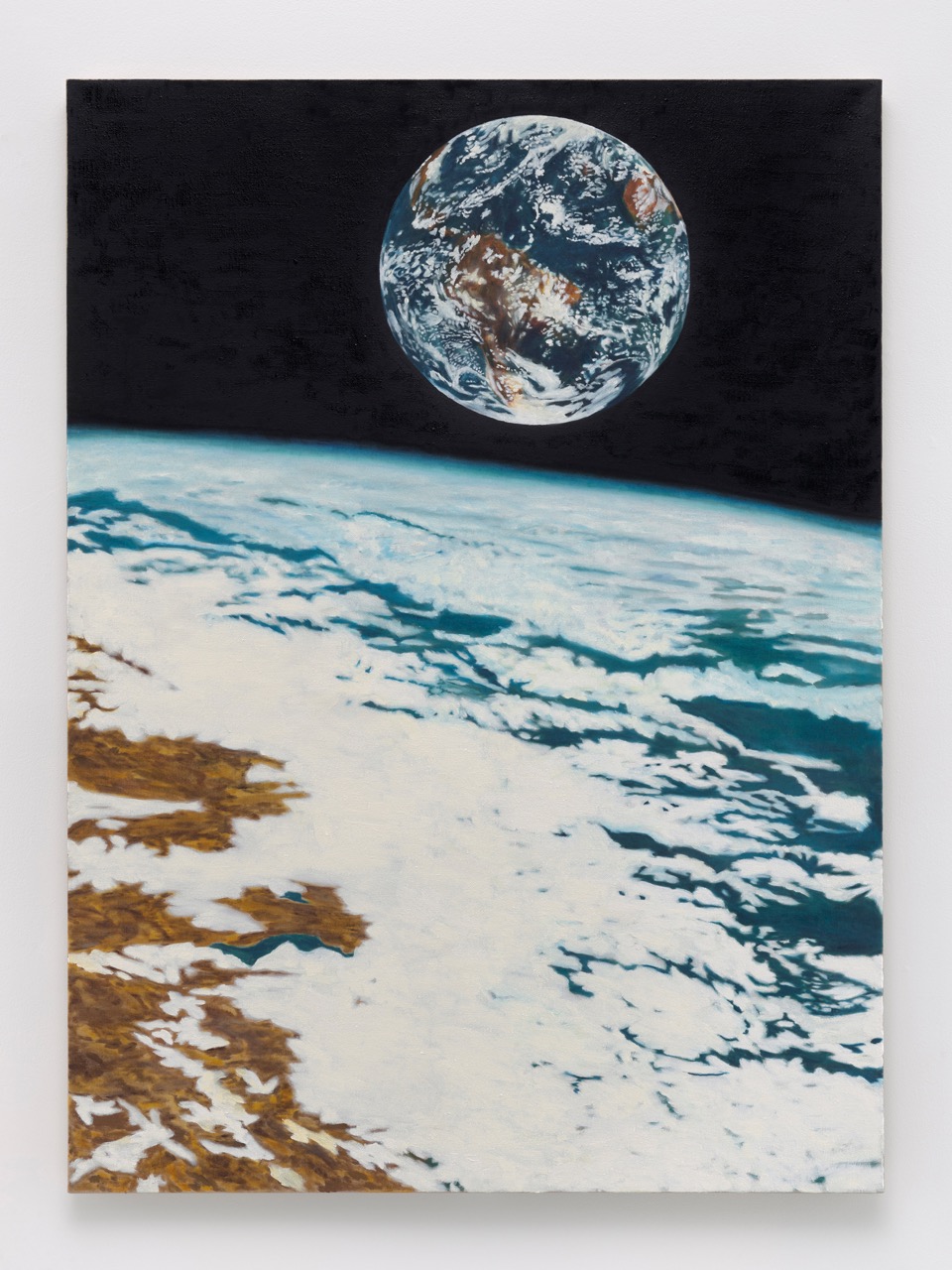

Leidy Churchman, Earth Bound (Card 21 of the Secret Dakini Oracle), 2020. Oil on linen, 58 1/8 × 42 3/4 inches. © Leidy Churchman. Image courtesy Matthew Marks Gallery. Photo: Ron Amstutz.

Yet, however prominent they are in this show, allusions to dharmic themes form just one category of image in a career that, on the whole, dissolves categories. (Although, I guess, that is itself a dharmic theme.) Churchman’s substantial body of paintings (a densely hung survey closed at the Hessel Museum in October) is known for its disarming variety of styles and subjects, and this new gallery show is no exception. Its title work, Earth Bound (Card 21 of the Secret Dakini Oracle) (2020), is based on a Tantric divination card. Resembling a new-age take on the 1968 photo Earthrise, which was snapped from the window of the Apollo 8, the cheesy yet poignant image shows our planet not from the moon’s orbit, but, impossibly, from the atmosphere of another, identical earth. A familiar brown and teal globe, marbled with clouds, appears like a long-lost twin, just above the glowing, misty horizon line of our current galactic home. Other images include a realist rendering of an iPhone 11 Pro; a Hallmark-ish close-up of roses in a mirrored frame; a small, orange grid of dots; an enormous, verdant panorama of Kishkindha (the mythic monkey kingdom in the Sanskrit epic Ramayana); and the big, flabbergasting, vaguely O’Keeffian abstract landscape Groundless Ground (2020).

Leidy Churchman, Groundless Ground, 2020. Oil on linen, 86 1/8 × 102 1/8 inches. © Leidy Churchman. Image courtesy Matthew Marks Gallery. Photo: Aaron Wax.

This is not to say that Churchman’s approach is one of purposeful incoherence or opacity; the radical heterogeneity is not random. But maybe it’s a little more mysterious than before. In the past, art-historical shout-outs to figures as diverse as Marsden Hartley and Barbara Kruger have mingled with careful facsimiles of book covers and inscrutable wildlife scenes to map a zigzagging, self-styled lineage. And intimate gestures of homage to contemporary queer and trans artists of Churchman’s own community—such as in a lovingly copied painting of a moody 2010 photograph from Every Ocean Hughes’s Christopher Street piers series, or a canvas depicting a realist sculpture of multimedia artist Juliana Huxtable—have offered a very specific, if fragmentary, view of a social and artistic cosmos. In Earth Bound, more often it’s a dizzying, impersonal cosmos that is explored—though with the same eccentricity and personal passion as before. And Churchman’s signature browser-cache quality still rules.

Leidy Churchman, iPhone 11, 2019–20. Oil on linen, 9 5/8 × 15 1/8 inches. © Leidy Churchman. Image courtesy Matthew Marks Gallery. Photo: Ron Amstutz.

On its face, such internettiness strikes as irreconcilable with a meditative state. To be mindful online—in a culture where the internet is synonymous with distraction and compulsion, on a day when I refresh my feeds between every clause and tumble headlong down a YouTube chute—feels impossible, paradoxical. But the riddle of Churchman’s weird attentive practice, with its calm handling of both information and paint, does seem to open up space. While the internet has changed our experience of the world, it has not changed the nature of experience itself. Being online, Churchman reminds us, with a guileless rigor that Trungpa might call “directness and unself-consciousness,” is actually just being.

Johanna Fateman is a writer, art critic, and owner of Seagull salon in New York. She writes art reviews regularly for the New Yorker and is a contributing editor for Artforum. She is a 2019 Creative Capital awardee and currently at work on a novel.