Shiv Kotecha

Shiv Kotecha

From limo to catwalk: the artist’s new round of celebrity portraits.

Sam McKinniss: Jonathan Taylor Thomas, installation view. Image courtesy the artist, JTT, and Almine Rech. Photo: Charles Benton. Pictured, left to right: JTT, Aaliyah, and Hallie and Annie.

Sam McKinniss: Jonathan Taylor Thomas, JTT Gallery, 191 Chrystie Street, New York City, through March 22, 2020

• • •

Of all the floppy-haired celebrity moppets on view in figurative painter Sam McKinniss’s new exhibition, Jonathan Taylor Thomas, I admit I crushed hardest on Thomas himself. With his whiz-kid wit brightening the otherwise inane sitcom Home Improvement, his premature chain-smoking rasp, and his ubiquity in cheap print magazines like Tiger Beat or Bop, the young actor stoked the fancy of many of us Clinton-era girls and gays long before any real Thomases could break our hearts. In McKinniss’s scintillating new suite of paintings and drawings, many of which are lush re-creations of popular images culled from the internet—paparazzi photos of Justin Bieber and Lindsay Lohan, for instance—he plays on notions of doubling and twinship. Consider my former crush’s fond sobriquet, JTT, which here echoes the name of the gallery where the exhibition takes place and its founder, Jasmin T. Tsou. It is the first of many reiterations, alter egos, afterlives, and anachronisms that appear within.

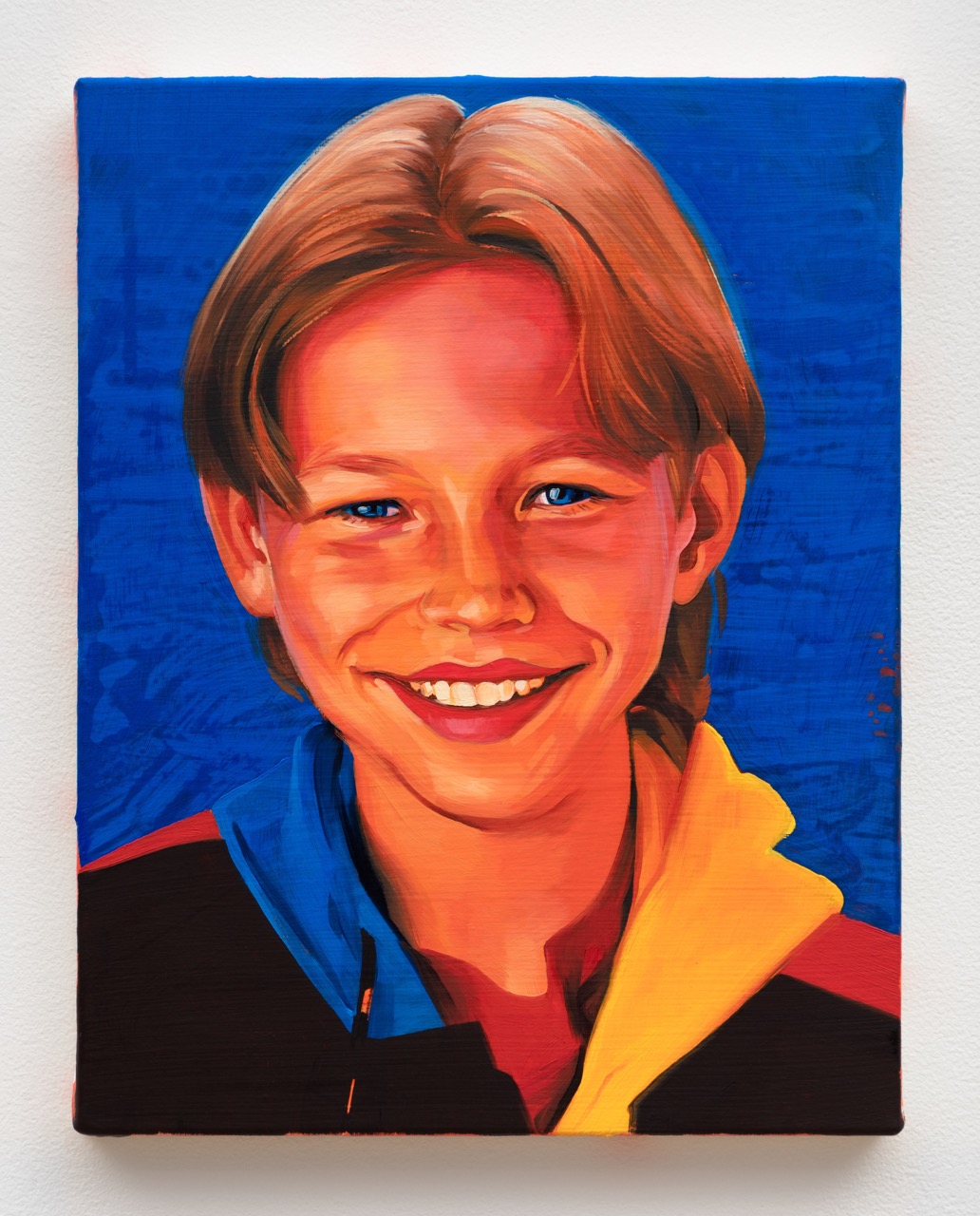

Sam McKinniss, JTT, 2020. Oil on canvas, 14 × 11 inches. Image courtesy the artist, JTT, and Almine Rech. Photo: Charles Benton.

Doubling, of course, lies at the heart of McKinniss’s appropriation-based technique. In a medium-sized portrait also titled JTT (2020), he renders the young actor’s supple flesh in pinks, oranges, and near-crimson tones, setting him up against a thick impasto background of cobalt blue. I recall the photograph McKinniss sourced for his portrait in an old issue of Bop, tucked between ads for acne care and stalkerish, who’s-dating-who-now gossip columns. Google Images pulls up several poor scans. In these derivatives of the magazine “original,” the boy’s flesh is drab, desaturate; you can see the grain of Bop’s low-budget, newsy paper stock. McKinniss, a remarkable colorist, uses chromatic saturation and contrast to heighten the drama—excuse me, dramedy—of Thomas’s cheeky headshot. The frame is tight, such that the boy’s pink head swallows the bulk of the canvas, and broad brushstrokes lift his cheeks into his eye sockets. JTT’s style was always understated, an always slick but dweeby paragon of cool. But here, he’s a ripened fruit. If he smiled any harder, he might just burst.

McKinniss is best known for single-figure portraits based on reproductions. Gracing the September 2019 cover of Artforum was his Star Spangled Banner (Whitney) (2017), a close-up shot of the late Whitney Houston’s benchmark performance of the national anthem at the 1991 Super Bowl. The image he chose to replicate portrays the singer mid-breath, pausing for a beat between verses. Seeing his memorial to our communal sex god, Prince—a massive repetition of the artist’s Purple Rain album cover made on the heels of the musician’s premature death—the precocious goth-pop chanteuse Lorde invited the artist to paint her portrait for her sophomore album, Melodrama. Here too, McKinniss used a photograph as his source. She’s supine, peaking out of hotel bedsheets with her hair draped over a pillow. A portrait of Lorde in sharp sapphire blues and creamy pinks and whites introduces us to her always maximal, high-drama electropop; McKinniss delivers her to us hiding between covers, restless and ready to love again.

Sam McKinniss: Jonathan Taylor Thomas, installation view. Image courtesy the artist, JTT, and Almine Rech. Photo: Charles Benton. Pictured, left to right: Lindsay, Pansies in a Basket (after Fantin-Latour), and The Olsens.

In his current exhibition, the painter’s implicit doubling is often literalized; for example, through dual portraits. Hallie and Annie (2020) depicts two freckled, doting Lindsay Lohans, based on a press picture from the actress’s breakout film, in which she plays identical twins, The Parent Trap (1998), itself a remake of the 1961 original. Another, Lindsay (2019), depicts a much older Lohan, this time coke-bloated and disconsolate, caught in a paroxysm of weeping. This painting hangs next to Pansies in a Basket (after Fantin-Latour) (2019), as if he’s presenting the Lohan as a cut flower. In The Biebers (2020), the stoned newlyweds, Justin and supermodel Hailey Rhode Bieber, stare blankly through the windshield of their big black car. What is it these two desire? I’m not sure what more I could want than the staccato patch of peach fuzz on Justin’s cheeks that, however anachronistically, McKinniss includes here; does Bieber still believe himself to be a kid? McKinniss reminds us otherwise. Giant swaths of black paint overtake the top and bottom of most of this canvas in long, unrelenting horizontal wipes, making the couple’s luxury, leather enclosure seems more like a coffin than a car. McKinniss infuses the genre of portraiture with the memento mori elements of still-life genre painting in his repetitions of contemporary figures. These paintings distort their living subjects into inanimate figures locked in space, like Keats’s mournful foster child, “of silence and slow time.”

Sam McKinniss, The Biebers, 2020. Oil and acrylic on canvas, 50 × 72 inches. Image courtesy the artist, JTT, and Almine Rech. Photo: Charles Benton.

This allusion to mortality—this inanimate quality—continues with The Olsens (2019), in which the child actresses turned designers, known to riff off each other’s flamboyant garb, sit together, funereal in black at New York Fashion Week. Their oversized, opaque sunglasses reflect back to us what they see: a glowing, empty runway. If portraiture is arguably based on some form of recognition—that of the observer recognizing the figure in the painting; or the painter, his subject; or, in this case, one twin recognizing the other—I’m not sure which takes precedent here. I notice that one Olsen, let’s call her Mary-Kate, extends a hand to the other, Ashley. This portrait towers with feeling, a conflation of anticipatory panic and a sisterly gesture of care. I clutch my pearls in their presence.

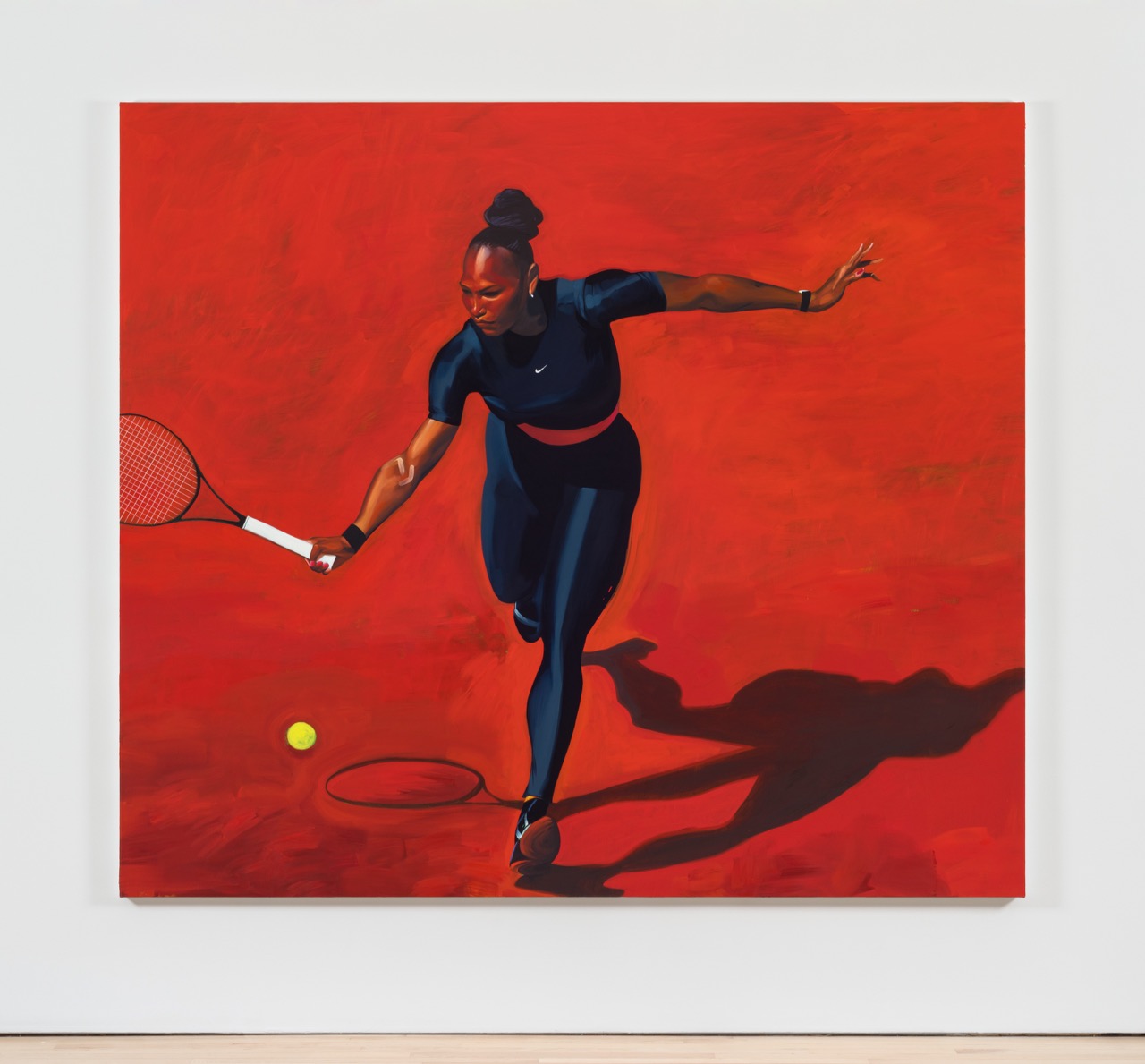

Sam McKinniss, Serena, 2019. Oil on canvas, 84 × 96 inches. Image courtesy the artist, JTT, and Almine Rech. Photo: Charles Benton.

The exhibition moves from its opening, a perverse study of smarmy childhood glee via JTT, through stoic glares at paparazzi, toward a different feat of performance in Serena (2019). In this looming portrait of tennis player Serena Williams, her majestic, strong body lunges forward in the center of the imposing canvas. Her arms are at full span as she bounds out of a blast of thick, layered vermillion to smack the ball across the court. Is she too playing doubles? Williams’s movement here reminds me of Jean Siméon Chardin’s Soap Bubbles (ca. 1733–34), where the viewer’s sight is drawn from the subject of the painting through a crisp line that splices the canvas to the image’s precarious, spherical object. McKinniss’s portrait of Serena aims to capture a similar feat of control—something like grace.

The show’s press release reminds us of psychoanalytic discourse on twinship and narcissism, and without a doubt, I see the dull face of my analyst in the eyes of many of these figures. McKinniss also pushes me to conjure up a figure of my own. I reproduce Goldie Hawn, wrapped in furs as Elise Elliot in The First Wives Club, whose plumped lips eject wisps of smoke and wisdom: “Youth and beauty, man! That’s the ticket.”

Shiv Kotecha writes poetry, fiction, and criticism. He is the author of two books, The Switch (Wonder, 2018) and EXTRIGUE (Make Now, 2018), and is a contributing editor for frieze magazine. He lives and works in

New York.