Sukhdev Sandhu

Sukhdev Sandhu

Mirth, melancholia, and surrealism on stilts: a retrospective of the

Black Wave director’s films.

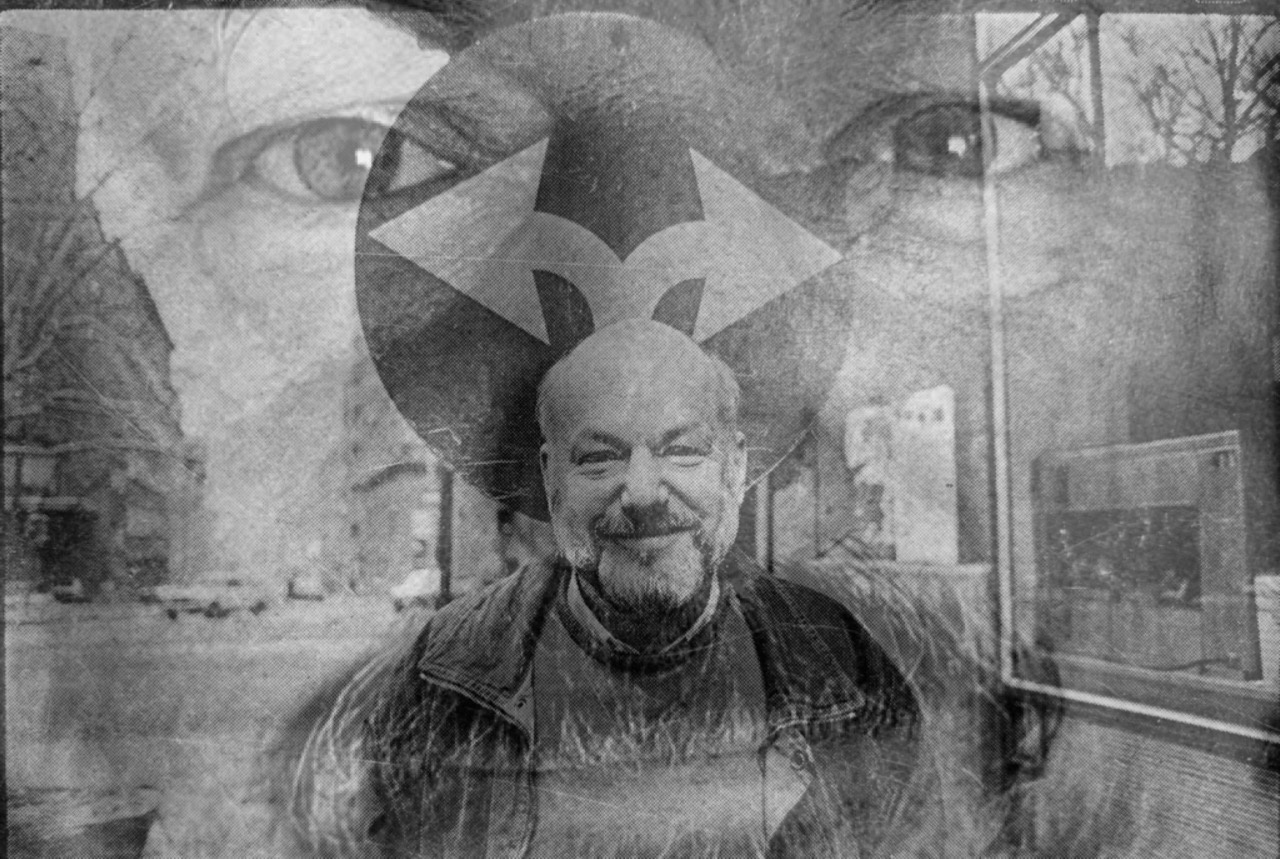

Dušan Makavejev. Image created by Hypnison.

“Dušan Makavejev, Cinema Unbound,” curated by Greg de Cuir Jr. and Pavle Levi, Anthology Film Archives, 32 Second Avenue, New York City, through March 8, 2020

• • •

The Yugoslavian film movement of the late 1960s and early 1970s was known as the Black Wave. How dark that sounds: so refusenik, so nihilist. That’s what the authorities thought too. The Black Wave was a pejorative term for films they regarded as anarchic, as cultural viruses, imaginative pornography. When Želimir Žilnik’s Early Works (1969), which dwells on the Belgrade student uprisings in and after 1968, was screened for President Tito, he allegedly halted the projection to demand, “What do these lunatics want?”

Small wonder, then, that Amos Vogel, champion of subversive cinema, was said to have described the Black Wave as “the freest, most radical, and most important film tendency” in Eastern Europe. The director he singled out as “the most illustrious example of this tendency” was Dušan Makavejev, who died at the age of eighty-six last year and is now the subject of a retrospective at New York’s Anthology Film Archives. Finally! The work of this merry, sagacious prankster has long been shrouded in tee-hee rumors and gossip, hardly known even among cinephiles. (“You could explain ex-Yugoslavia as an editing disaster—a chain of rough cuts in the hands of incompetent editors and frightened directors,” he once claimed.)

Janez Vrhovec as Jan and Milena Dravić as Rajka in Man Is Not a Bird. Image courtesy Anthology Film Archives.

Makavejev’s debut feature, Man Is Not a Bird (1965), is a revelation, an exhalation. Bringing Nouvelle Vague brio and eroticism to Soviet Bloc landscapes, it charts the brief and probably doomed relationship between a skilled engineer, Jan (Janez Vrhovec), who arrives in a mining town to organize the installation of major new equipment, and a blonde hairdresser, Rajka (Milena Dravić), who finds him lodgings at her parents’ small home.

Jan is a scion of socialism, serious to the point of being lugubrious, unfazed by turbo machines and the stilted language of management productivity. Has he been crippled by the state’s fairy tales about what heroic manhood looks like? Rajka’s achievement is to locate his beating heart, to show how he, like many of the construction workers he scolds and disciplines, has errant feelings, appetites that can be repressed but never snuffed out.

Man Is Not a Bird. Image courtesy Anthology Film Archives.

Even here, early on in his career, Makavejev gives centrality to a female actor, the extraordinary Dravić, who combines devil-may-care youthfulness, simmering carnality, and old-beyond-her-years sorrow. Handheld cameras lend genuine volatility to many scenes. Minor characters, among them mesmerists, ex-circus performers, and womanizers, often appear to be walking a fine line between carnivalesque rambunctiousness and fomenting mass rebellion.

Eva Ras as Izabela in Love Affair, or the Case of the Missing Switchboard Operator. Image courtesy Anthology Film Archives.

Upping the ante formally is Love Affair, or the Case of the Missing Switchboard Operator (1967). Charting another probably doomed romance—this one between telephone employee Izabela (Eva Ras) and Muslim sanitation inspector Ahmed (Slobodan Aligrudić)—it might at first suggest a crime-fiction B movie. But Love Affair is intercut with sequences in which authority figures discourse knowledgeably yet uselessly; unusually frank (for the time) scenes of the lovers exploring each other’s bodies; and documentary-style passages that show Belgrade in the throes of modernization. Izabela is Hungarian, Ahmed (whom at one point she calls “Suleiman the Magnificent”) possibly Romanian, and throughout there’s a barely warded-off specter of this turning into an Ali: Fear Eats the Soul–style fable.

Eva Ras as Izabela in Love Affair, or the Case of the Missing Switchboard Operator. Image courtesy Anthology Film Archives.

Then again, as with all Makavejev’s films, melancholia must wrestle with mirth. There’s an ongoing tension between the sadness of everything and a joy formidable. Love Affair prickles with possibility: the way Izabela tickles Ahmed’s back with grapes, the cat (the forever symbol of ineffability and sensual potential) on her naked back, the bubble she blows in her kitchen. (“Bigger!” you want to cry. “Bigger still! Even bigger!”) Together, for a brief moment, they represent the hopes of a new kind of socialist nation, one very different from the country saluted in the choleric, raspy anthem “Be Proud, Yugoslavia!” blaring in many scenes.

Ivica Vidović as Vladimir Ilyich, Jagoda Kaloper as Jagoda, and Milena Dravić as Milena in WR: Mysteries of the Organism. Image courtesy Anthology Film Archives.

Best known, of course, is the documentary-fiction hybrid WR: Mysteries of the Organism (1971), less a biography of sex-positive Austrian psychoanalyst Wilhelm Reich and more a steaming Balkan bouillabaisse of cinematic shock therapy and countercultural wassailings. Reich, who died in a US jail in 1957, emerges as a psychic freedom fighter trying to rescue America from itself, his liberation theology resonating with freaks and dissenters such as pro-masturbation pedagogue Betty Dodson; Screw magazine coeditor Jim Buckley, seen in the film having his erect penis cast in plaster; and Tuli Kupferberg of avant-neanderthal rock band the Fugs (best known for “Kill for Peace”), who runs around downtown New York dressed in fatigues and carrying a rifle. All this and a radical young woman back in Yugoslavia who has sex with—and gets decapitated by—a Russian ice skater called Vladimir Ilyich.

WR was verboten in Yugoslavia and Makavejev went into exile, making his next film, Sweet Movie (1974), in Canada, France, and Holland. To taxonomize it would challenge the most inventive Pornhub programmer. It’s a sort-of Satyricon, panto-season Viennese Actionism, surrealism on stilts. Briefly, it involves a “Most Virgin” contest won by a woman (Carole Laure) whose new husband, the richest man on the planet, is fond of giving golden showers. She is nearly drowned in a pool, hidden by a black bodybuilder in a milk bottle–shaped loft, squeezed into a suitcase, and sent to Paris, where she winds up having public sex at the Eiffel Tower with Latin singer El Macho (played by Sami Frey). She then undergoes regression therapy in a commune run by infamous Austrian artist Otto Muehl, before finally drowning in a vat of chocolate.

Pierre Clémenti as Potemkin and Anna Prucnal as Anna Planeta in Sweet Movie. Image courtesy Anthology Film Archives.

This barbed picaresque is counterposed with the story of Anna Planeta (Anna Prucnal), an idealistic woman who heads down the canals of Amsterdam in a boat called Survival that has a huge papier-mâché head of Karl Marx on its prow. She brings aboard a bike-riding sailor known as Potemkin (Pierre Clémenti), makes love to him, then stabs him to death in a bed of sugar. She also dances naked before young boys.

Pierre Clémenti as Potemkin and Anna Prucnal as Anna Planeta in Sweet Movie. Image courtesy Anthology Film Archives.

Words can’t do justice to Sweet Movie. It makes the punky wildness of Věra Chytilová’s Daisies (1966) seem like a lunchtime recital. The violence of capitalism and the violence of communism, their equally self-serving claims to reason and enlightenment, their amnesia and their historical mendacities (the film’s biggest obscenity is its archival footage of the Katyn massacre, in which more than 14,000 Polish prisoners of war were buried in a mass grave), their false promises and the perversities they spawn: Sweet Movie can’t hope to control the chaos it unleashes. Banned in many countries and very nearly destroying Makavejev’s career, it is, in its own lysergic fashion, an unforgettable demonstration of his belief that the “main work of film art is to transform heavy and difficult and confusing and ugly questions of human existence into something close to a song or a flying carpet.”

Sukhdev Sandhu directs the Colloquium for Unpopular Culture at New York University. A former Critic of the Year at the British Press Awards, he writes for the Guardian, makes radio documentaries for the BBC, and runs the Texte and Töne publishing imprint.