Melissa Anderson

Melissa Anderson

An iconic work from the late Jean-Jacques Beineix, pioneering French director of the ’80s cinéma du look movement.

Thuy An Luu as Alba and Frédéric Andréi as Jules in Diva. Courtesy Rialto Pictures.

Diva, directed by Jean-Jacques Beineix, Film Forum, 209 West Houston Street, New York City, through May 5, 2022

• • •

French film since 1958 has been defined by so many waves that the nation’s cinema conjures images of endless oceanic churn or trigonometry graphs. The freewheeling experimentation of the Nouvelle Vague auteurs (as exemplified by Jean-Luc Godard) that dominated the ’60s begat a post–New Wave cadre of directors, including Philippe Garrel, Maurice Pialat, and Jean Eustache, whose work, particularly in the ’70s, was more corrosively somber and personal. At the dawn of the ’80s, the tide turned once more, as the new New Wave began to rise. Diva, Jean-Jacques Beineix’s voluptuous 1981 debut, was the first entry in this canon, and its weeklong revival at Film Forum, where it will be shown on 35mm, is a fitting salute to the director, who died this past January, at age seventy-five.

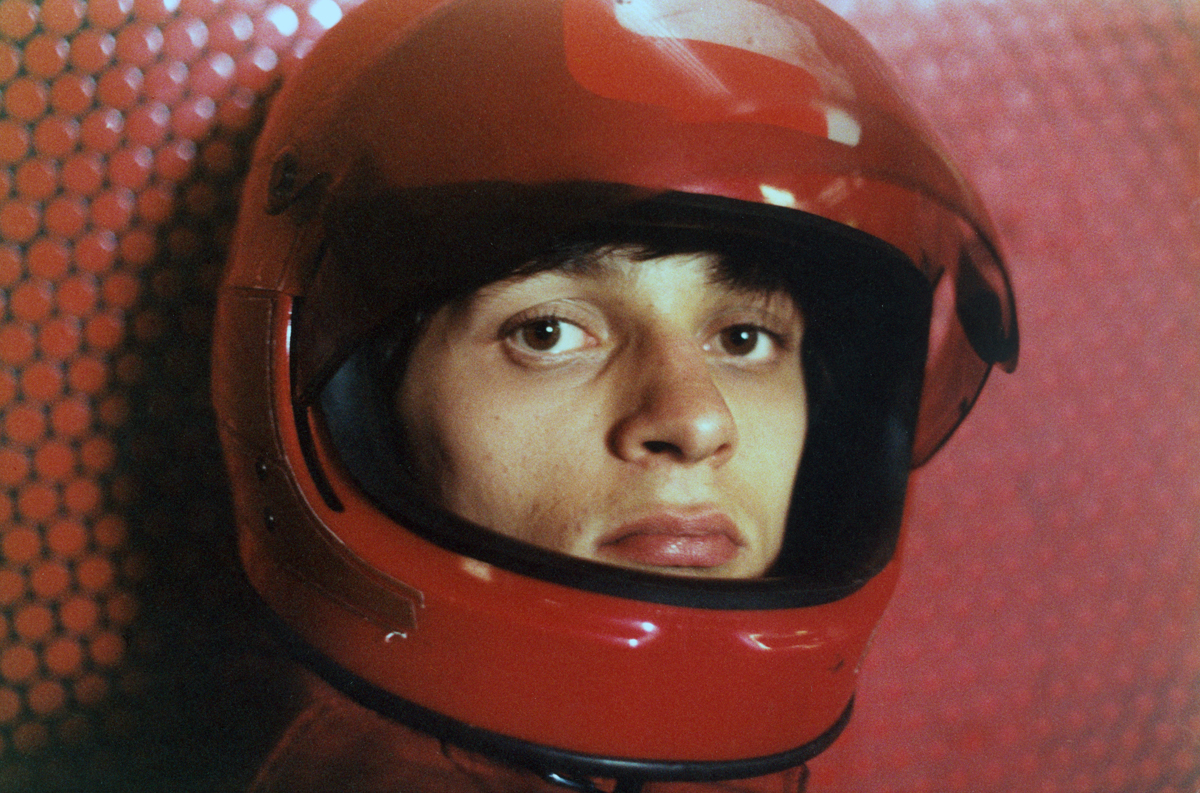

Frédéric Andréi as Jules in Diva. Courtesy Rialto Pictures.

The new New Wave is better known as the cinéma du look, a term that was applied retrospectively in 1989 by French film critic Raphaël Bassan, who singled out Beineix—and his younger confrères in the movement, Leos Carax (Bad Blood, 1986) and Luc Besson (Subway, 1985)—for his gossamer artifice, jagged romanticism, and striking color palette. Bassan deployed his franglais term as an insult. But the look of cinéma du look proved auguring and enduring: MTV, that seedbed of pop postmodernism, launched five months after Diva premiered, and filmmakers around the globe in the decades that followed, not least Michael Mann and Wong Kar-wai, developed their own look-isme.

Wilhelmenia Wiggins Fernandez as Cynthia Hawkins in Diva. Courtesy Rialto Pictures.

As the title implies, Diva—which Beineix, along with co-screenwriter Jean Van Hamme, adapted from the 1979 novel of the same name—revolves, sometimes tangentially, around an opera star. Reedy, saucer-eyed Parisian postman Jules (Frédéric Andréi) is besotted with American soprano Cynthia Hawkins (Wilhelmenia Wiggins Fernandez, cast by Beineix after he was dazzled by her Musetta in a 1980 production of La Bohème at the Paris Opera), who has never allowed her singing to be released on an album. (“A concert is a privileged moment for the artist and her audience. . . . Music, it comes and goes. Don’t try to keep it,” she imperiously explains at a press conference.) He sneaks a Nagra into the tatty Théâtre des Bouffes du Nord to record her performance of an aria from 1892’s La Wally. (In its obsession with the beauty and power of the human voice, Diva might also be thought of as an illustration of the cinéma du listen.) But that’s not the mail carrier’s only illicit act that night. Backstage, Jules also steals one of Cynthia’s gowns (which he’ll later drape around his neck like an aviator’s scarf), a pilfering that makes the front page of France-Soir the next day.

Wilhelmenia Wiggins Fernandez as Cynthia Hawkins in Diva. Courtesy Rialto Pictures.

Jules’s surreptitious recording spawns a busy, byzantine plot. Unbeknownst to him, two Taiwanese music executives at the Wally recital espied his piracy and are now hotly pursuing him and the tape. The waiflike letter carrier is also the quarry of two additional dyads—a thug duo and a pair of cops—who want to retrieve another recording, but one that Jules has no idea he possesses: an audio cassette made by a sex worker that’s filled with incriminating evidence about the leader of a drug and prostitution ring, which she deposits in his moped mail pouch seconds before she is murdered. Aiding and advising Jules is an odd couple consisting of teenage wiseacre Alba (Thuy An Luu) and the much older guy she lives with, Serge (Richard Bohringer), a quasi-mystic sybarite fond of long tub soaks and proffering lessons on the zen of buttering baguettes.

Gérard Darmon and Dominique Pinon as two thugs named the Caribbean and the Priest in Diva. Courtesy Rialto Pictures.

The diverting, serpentine storyline crackles with two terrific chase scenes. In the first, Jules eludes capture by navigating his scooter through the confounding terrain—stairs, escalators, corridors, moving walkways—of the Métro. In the second, the postman, now injured and wearing a red jacket that calls to mind James Dean’s iconic outerwear in Rebel Without a Cause, staggers through a subterranean video arcade and bowling alley, his bloodied, feeble frame invisible to the pinball wizards illuminated by neon.

Frédéric Andréi as Jules and Thuy An Luu as Alba in Diva. Courtesy Rialto Pictures.

But Diva prizes episodes of calm too. Moments of repose inside Jules’s residence—a loft, bathed in blue light, above a garage filled with mangled luxury cars—allow us to linger on the fanciful décor, namely a series of murals that suggest Ed Ruscha by way of Patrick Nagel. Serge’s unpartitioned living space, near the bank of the Seine and so vast that Alba can glide on quad skates around it, displays a more minimalist, coherent aqua-and-white motif, hues that dominate the enormous jigsaw puzzle he’s completing, the crushed packs of Gitanes next to it, and the wave-motion machine that focuses his thinking.

Unquestionably, Beineix’s film delights, if not overwhelms, the eye. Yet it also brims with moony emotions, presenting Jules’s borderline-deranged fandom as an exalted form of love. Even regal Cynthia is moved when the stripling, full of contrition, shows up at her luxe hotel suite to return her off-white silk garment. She’s so touched, in fact, that she grants him a privilege never offered to anyone else before: the opportunity to listen to her rehearse, as she accompanies herself on the piano to “Ave Maria.” Supplicant and star saunter through the city just before daybreak, as he gallantly holds an umbrella over his idol to protect her from a light mist. Their romance is consummated with a chaste gesture, his hand tentatively placed on her shoulder.

Wilhelmenia Wiggins Fernandez as Cynthia Hawkins and Frédéric Andréi as Jules in Diva. Courtesy Rialto Pictures.

Diva’s bewitchery hasn’t dimmed more than forty years later. Its history and its place in Beineix’s oeuvre add to its appeal. Diva would mark Wiggins Fernandez’s lone screen appearance; for many in the cast, particularly Andréi, it remains the film for which they’re best-known. Beineix made his last film in 2001 (a short and two TV documentaries followed), none as popular as his first, though his third, Betty Blue (1986), which launched the career of gap-toothed Béatrice Dalle, one of France’s most fearless actresses, came close.

The most touching tribute to Beineix and the aesthetic he was so instrumental in creating arrived just a few months before he died. Released this past October, Joanna Hogg’s highly autobiographical The Souvenir Part II, about her time in film school in the UK during the mid-’80s, features a classmate who had loved Diva and is now helming her own ultrachic spectacle. Her ardor for Beineix’s movie rivals that of Jules for Cynthia’s voice.

Melissa Anderson is the film editor of 4Columns. Her book on David Lynch’s Inland Empire is available from Fireflies Press as part of its Decadent Editions series.