Melissa Anderson

Melissa Anderson

A retrospective presents the celebrated Japanese actress’s shift

to filmmaking.

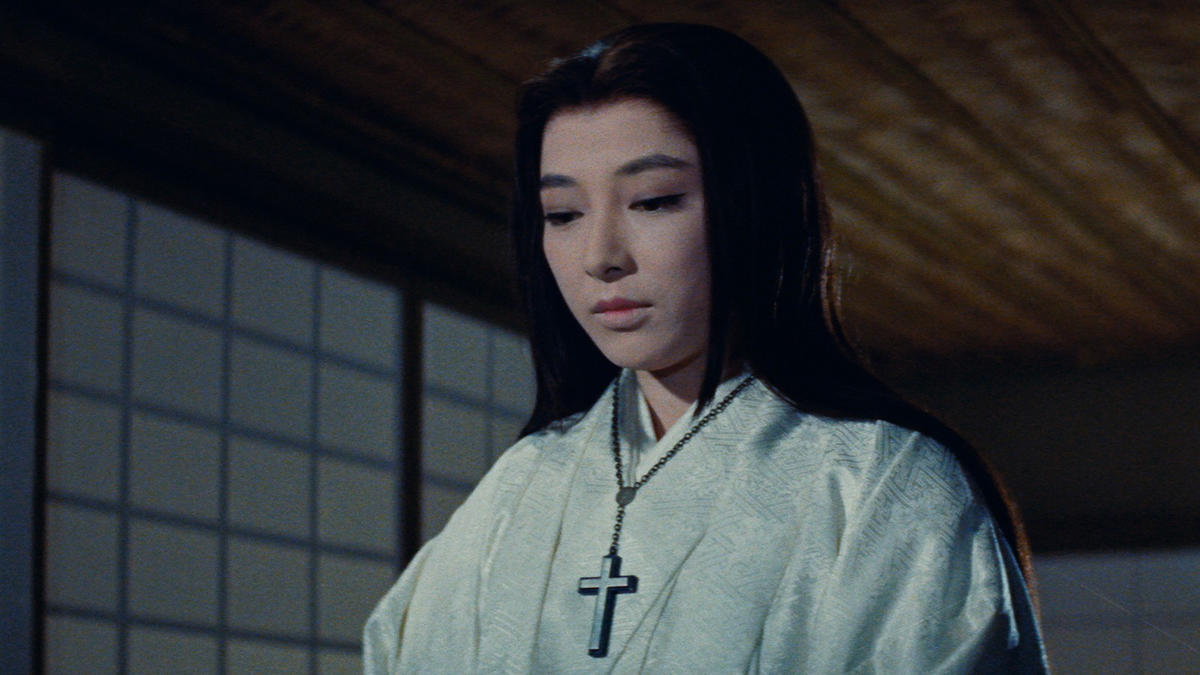

Ineko Arima as Ogin in Love Under the Crucifix. Courtesy Cinetic Media.

“Kinuyo Tanaka,” Film at Lincoln Center, New York City,

March 18–27, 2022

• • •

One of the most famous actresses of Japanese cinema is also one of its least-known filmmakers. Kinuyo Tanaka (1909–77), who starred in several ravishing works by titans Yasujirō Ozu, Mikio Naruse, and Kenji Mizoguchi, helmed six narrative features between 1953 and 1962, becoming Japan’s second female director. (Tazuko Sakane, whose talents were expressed exclusively behind the camera and whose films were primarily educational, was the first.) A retrospective at Film at Lincoln Center brings together the half-dozen films that Tanaka made, all in new digital restorations, plus another six movies, screening on 35mm, that showcase some of her most transporting performances. The double tribute promises two types of ecstasy: seeing unsung films for the first time and (re)watching canonical titles with a new appreciation for a singular figure.

Tanaka made her screen debut at fourteen in 1924; by the 1930s, she was one of the biggest female stars affiliated with Shōchiku studios, among prewar Japan’s most significant film companies, for which she worked exclusively until 1950. Her first decade as a freelance actress coincided with the anni mirabiles of Japanese cinema’s fertile postwar golden age. In 1952 alone she gave two of her most celebrated performances: as the title character in Mizoguchi’s The Life of Oharu, a wrenching Edo-era melodrama that traces a woman’s deepening debasement and perhaps the most enduring of the fourteen films they made together; and as the resilient but tender matriarch in Naruse’s Mother, a movie that brought her international acclaim.

Kinuyo Tanaka as Oharu in The Life of Oharu. Courtesy Cinetic Media.

Despite these triumphs, though, Tanaka, by then in her forties, would see diminishing opportunities to play compelling parts (she continued to act until 1976, the year before she died at age sixty-seven of a brain tumor). Spouseless her whole life, she was fond of saying that she “chose to marry cinema.” Her transition to directing was one way to reinvigorate those vows, a move made possible in part by the new rights and freedoms given to women that were codified in Japan’s postwar constitution. “Women’s advancement became evident in every aspect of society, including the entrance of women in parliament. . . . I too felt like trying to do something new by working as a female director,” Tanaka once said.

Masayuki Mori (left) as Reikichi Mayumi in Love Letter. Courtesy Cinetic Media.

Her career shift was supported by key male collaborators (but notably not by Mizoguchi, who publicly opposed her desire to direct). Naruse, for example, hired Tanaka as his assistant during the production of Older Brother, Younger Sister (1953). Keisuke Kinoshita, with whom Tanaka first worked in Army (1944)—playing a mother who, in the infamous final scene, wordlessly, tearfully runs alongside her son as he marches off to war, laying bare the film’s decidedly anti-martial stance—wrote the screenplay for her directorial debut, Love Letter (1953), a Tokyo-set melodrama about a doleful ex-soldier and part-time scribe of billets-doux (Masayuki Mori) who grows even more disconsolate when he discovers that his childhood sweetheart was sexually involved with an American serviceman shortly after the war.

Mie Kitahara as Setsuko Asai and Shōji Yasui as Shōji in The Moon Has Risen. Courtesy Cinetic Media.

Ozu gave Tanaka a script that he originally wrote in the late ’40s, which became the basis for her second feature, The Moon Has Risen (1955). In this tender romantic comedy, Chishū Ryū—best known for the emblematic father roles he portrayed for Ozu in Late Spring (1949) and Tokyo Story (1953)—plays Mr. Asai, a widowed dad of three adult daughters. The youngest, Setsuko (Mie Kitahara), delights in concocting, sometimes with the assistance of her James Joyce–loving translator boyfriend, Shōji (Shōji Yasui), convoluted matchmaking strategies to pair her middle sibling with an old pal of her beau’s. One of these schemes finds Setsuko coaching Yoneya—the Asais’ tremulous maid, played by Tanaka—to pretend to be someone else over the phone. The scene affords the wry pleasure of watching the veteran actress and sophomore director being “directed” by then-rising talent Kitahara. (She’d quit movies just five years later, after marrying her frequent costar Yūjirō Ishihara; for many Japanese actresses at the time, matrimony was followed by early retirement.)

Machiko Kyō as Ryūko Korinkakura in The Wandering Princess. Courtesy Cinetic Media.

Appearing on both sides of the camera for The Moon Has Risen—as she did in other small roles in two other movies she helmed—Tanaka calls to mind Ida Lupino, the great Hollywood noir actress who directed seven features from 1949 to 1966, including 1953’s The Bigamist, in which she also starred. But Lupino, whose output as an auteur consisted of tightly budgeted melodramas, noirs, and a manic teen comedy, never took on productions as enormous in scale as Tanaka’s The Wandering Princess (1960), her first film in color and in Cinemascope. Based on the 1959 memoir of Hiro Saga, a Japanese noblewoman who married a Qing dynasty imperial prince in 1937, Tanaka’s movie depicts its protagonist, played by Machiko Kyō, stoutly pressing on amid the numerous invasions and shifting allegiances within Japanese-controlled Manchuria. Love Under the Crucifix (1962), Tanaka’s directorial swan song, was similarly ambitious: a jidai-geki, or period drama, ablaze in primary hues, set in the late sixteenth century. Following the impossible yet inextinguishable ardor between Ogin (Ineko Arima), the daughter of a tea master, and Ukon (Tatsuya Nakadai), a married, pious Christian samurai, Love Under the Crucifix abounds with febrile declarations. My favorite: “I will never regret being in hell with you.”

Yumeji Tsukioka (right) as Fumiko Shimojō in Forever a Woman. Courtesy Cinetic Media.

However sweeping and vast those two epics may be, no film by Tanaka quite matches the devastating power of her third, Forever a Woman (1955), sometimes known as The Eternal Breasts. Inspired by the real, too-short life of a lauded tanka poet, Tanaka’s movie centers on Fumiko (Yumeji Tsukioka), the beleaguered wife of a self-pitying philanderer and the mother of two small children, who finds some solace in workshopping her verse at her poetry club. Shortly after divorce frees her from her tyrannical spouse, she is diagnosed with breast cancer—a condition treated with stark candor in Tanaka’s film, never more so than during the scene set in the operating room where Fumiko undergoes a double mastectomy. She assuages her pain by devoting herself more fervently to her work—one of her poems is titled “Lost Bosom”—which soon attracts the attention, and more, of a handsome journalist (Ryōji Hayama). Ailing, Fumiko burns with passion. “I want to die as the sinful human I am,” she cries out. As both an actress and a director, Tanaka never lets us forget the exquisite sorrow of being alive.

Melissa Anderson is the film editor of 4Columns. Her book on David Lynch’s Inland Empire is available from Fireflies Press as part of its Decadent Editions series.