Johanna Fateman

Johanna Fateman

Sculptures that clank, smack, bloom, slip, and drape.

Liz Larner, Corner Basher, 1988. Steel, stainless steel, electric motor, speed control, 106 × 36 × 36 inches. Courtesy Gaby and Wilhelm Schürmann Collection.

Liz Larner: Don’t put it back like it was, curated by Mary Ceruti, organized by Kyle Dancewicz, SculptureCenter, 44-19 Purves Street,

Long Island City, New York, through March 28, 2022

• • •

Liz Larner’s retrospective, her largest since 2001, starts with a bang: a small steel wrecking ball on a clanking chain swings from a nearly ten-foot pole to smack a pair of intersecting walls, expanding or deepening two kitty-corner wounds of exposed gypsum and tattered paper with each revolution. Standing like a sentry or a carnival barker just outside the entrance to SculptureCenter’s ground-floor gallery, the motorized Corner Basher (1988) is controlled by an on-off switch and a speed dial. Visitors are invited to use them and thus to begin the experience of the exhibition with their senses awakened, not just by the dangerous sculpture’s auditory and vibratory effects and its towering silhouette, but by the thrill of destruction.

Liz Larner: Don’t put it back like it was, installation view. Pictured: Liz Larner, Corner Basher, 1988 (detail). Steel, stainless steel, electric motor, speed control, 106 × 36 × 36 inches. Courtesy Gaby and Wilhelm Schürmann Collection. Photo: Cathy Carver. © Liz Larner.

Larner described Corner Basher in milder terms, though, when speaking to an interviewer recently, calling it “a subtractive sculpture made by a group of people who don’t know each other.” It’s notable that she identified the battered drywall, not the basher, as the art. (The machine she called an “instrument.”) But whether the piece is a kinetic sculpture or interactive process art, whether it’s confrontationally feminist or dispassionately conceptual, it’s an apt starting point for a consideration of her varied body of work. Don’t put it back like it was, as the Los Angeles artist’s show is titled, includes twenty-eight sculptures spanning 1987 to 2021, from her experiments with bacterial blooms and industrial materials to her later, painterly engagement with epoxy and ancient ceramic techniques.

Liz Larner: Don’t put it back like it was, installation view. Pictured: Liz Larner, Orchid, Buttermilk, Penny, 1987. Orchid, buttermilk, penny, glass, 43 7/16 × 17 1/2 × 10 1/8 inches. Photo: Cathy Carver. © Liz Larner.

Wordplay in titles, and a companion poetic approach to materials, is one thread connecting dissimilar sculptures. Among the earliest objects on view are the petri-dish compositions of Cultures (1987–), which wryly combine artifacts of human civilization with microorganisms in an agar growth medium to literally and/or metaphorically feed off one another. Orchid, Buttermilk, Penny (1987) shows the title’s elements, including its once-bright flower, as capsules of brown decay, in a vitrine mounted on a distressed plywood plinth. In Primary, Secondary: Culture of Empire State Building and Twin Towers (1988), petri dishes are again featured, this time divided into quadrants, filled with dark-hued samples and displayed on two levels of a curious glass and aluminum structure—a miniature, abstract skyscraper. And though Out of Touch (1987), a spherical floor sculpture resembling a small, mummified boulder or giant ball of twine, seems on its face to be nothing like this delicate bacteria-and-architecture-based sculpture, the checklist offers that it is made from sixteen miles of surgical gauze. Larner seems to be playing with notions of monumentality—by scaling down American symbols of technological and economic power, representing these obelisks as biomes in one instance, and by compressing an enormous, almost incomprehensible length of material into a comic lump in another.

Liz Larner: Don’t put it back like it was, installation view. Pictured, left: Liz Larner, Out of Touch, 1987. Pictured, right: Liz Larner, Bird in Space, 1989. Photo: Cathy Carver. © Liz Larner.

Art historian Connie Butler, in an essay for the accompanying catalog, notes the artist was influenced as a student at CalArts in the ’80s by the book Let’s Take Back Our Space (1979)—a vast, illustrated taxonomy of gendered body language in art history and public space by German photographer Marianne Wex. While it’s far too simple to read Larner’s overarching project as a rebuke of manspreading or the historically feminine tendency to fold and shrink, there is a caustic insouciance—in the first half-decade or so of her practice in particular—that seems bent on subverting such embodied binaries.

Liz Larner, Lash Mat, 1989 (detail). Leather, false eyelashes made from human hair, glue, 122 1/2 × 11 1/2 × 3/8 inches. Photo: Cathy Carver. © Liz Larner.

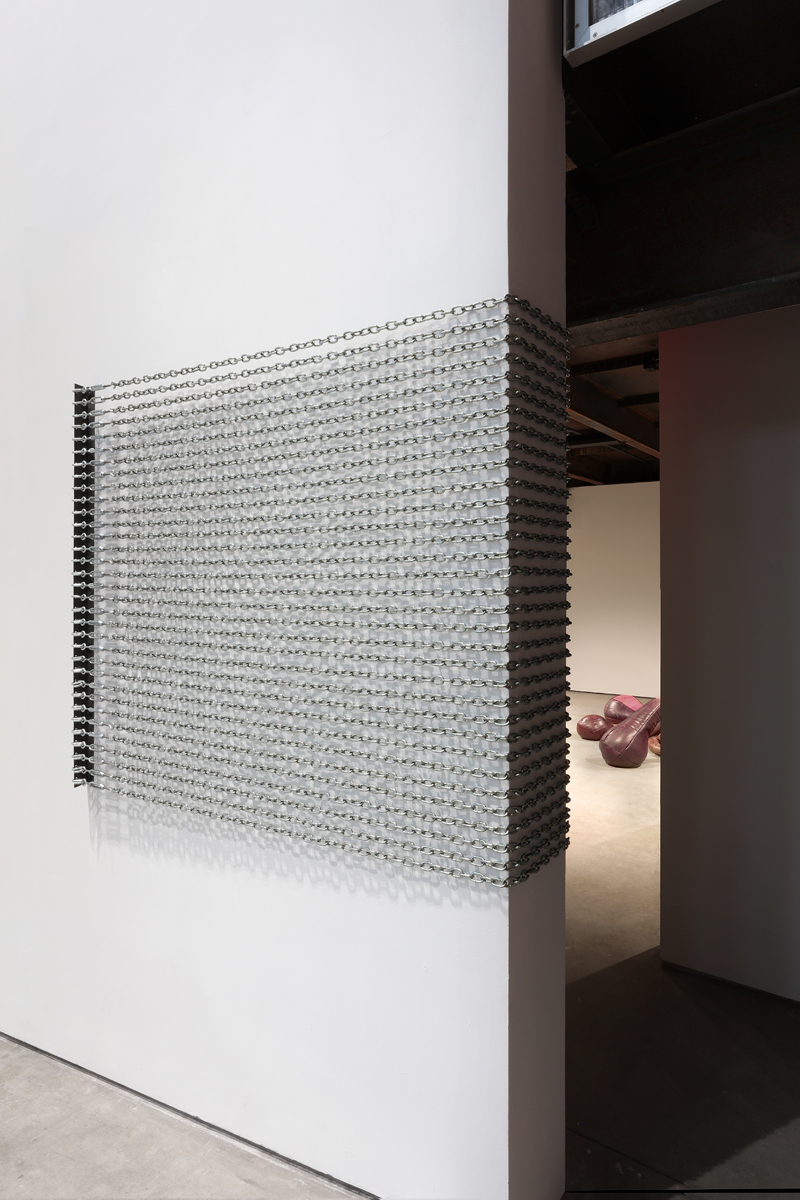

The elegantly unsettling Lash Mat (1989) is a wall-based work in which a long column of leather spills onto the floor to curl like a furry tongue, countless dense lines of glued-on false eyelashes rendering it surreally obscene, the bold geometry of its form and the grotesque excess of its top layer at odds with the demure associations of the fragile cosmetic accessories that flock it. Wrapped Corner (1991) is a rather butch use of hardware, a severe configuration of chain, whose cold stripes make a ninety degree turn around the edge of a wall in a gesture of containment and creeping movement; in contrast, Too the Wall (1990) uses steel to span a corner—or to block it off with a kind of delicate passive aggression—employing an expanding succession of spidery, necklace-like lines. No M, No D, Only S & B (1990), whose cryptic title refers to a parentless family (with only sisters and brothers), is a rhizomatic, scrotal cluster of leather bulbs, which threatens to grow in all directions, it seems, recalling boxing gloves with its bloated, sewn construction. And Bird in Space (1989) is a feat of taut nylon rope, a shimmering, airy, impermanent interpretation of Brâncuși’s lithe, vertical creature, which (unlike his solid, one might say phallic, version) spreads its wings in an extravagant, variable use of space. (The cords must be extended or anchored differently according to the dimensions of its venue.)

Liz Larner: Don’t put it back like it was, installation view. Pictured, left: Liz Larner, Wrapped Corner, 1991. Pictured, right: Liz Larner, No M, No D, Only S & B, 1990. Photo: Cathy Carver. © Liz Larner.

While this era of production occupies SculptureCenter’s more conventional, white cube-ish ground level, works from the current millennium hold their own against (or thrive in) the more unusual, potentially distracting, ambience of the basement, which—with its low concrete archways and crumbling surfaces—conjures subterranean aqueducts and “Cask of Amontillado” murder tunnels. It’s still a retrospective, of course, and the history lesson continues for those following along, but here, Don’t put it back turns into something to lose yourself in. The bronze woman of You might have to live like a refugee (2019)—a figurative outlier resembling nothing else on view—slips like a ghost into a wall, symbolizing the apocalyptic pressures of war and climate crisis on Larner’s thinking. (She chose the phosphorescent color of the spectral refugee, Larner tells curator Mary Ceruti, for its symbolic meaning: “I hope that this green calls to mind not only ancient bronze sculptures but also ecofeminism in relation to the current, highly charged moment of immigration around the world.”) A long corridor of wall-based, glazed-ceramic works—big bifurcated ovals with a ruined, archaeological cast to them, reminiscent of Lynda Benglis’s early wax paintings—come off as alchemical accidents or alien tablets. Pieces such as the cracked, mineral-studded, oceanic blue vi (calefaction) (2015) might be an exquisite warning of coming entropic disorder. And delicate metalwork clusters, which look like tangled jewelry or sections of decorative chainmail, are placed in unexpected spots—the gold-plated Guest (2004) is draped around a rust-colored conduit emerging from a hole—proving Larner’s enthusiasm for the unique features of the raw space and her commitment to her exhibition title’s imperative.

Liz Larner, Guest, 2004. Gold-plated bronze, square section, dimensions variable. Photo: Cathy Carver. © Liz Larner.

Don’t put it back like it was charts her eccentric career, though the show’s unchronological arrangement (and challenging exhibition map) doesn’t illuminate a progression or trajectory, exactly. It creates the impression of simultaneity instead, which is ultimately a more accurate representation of her untamable, heterogeneous practice of object-making and intervention. Larner has moved abruptly at times, pursuing ideas rather than a look, perhaps testing the material, spatial possibilities for the radical, open-ended suggestion of Wex’s book, its implications for things other than a body. Let’s take back our space is a heady incantation, one which might lead absolutely anywhere—it makes sense to invoke, right off the bat, the somatic power and creative gesture of demolition.

Johanna Fateman is a writer, art critic, and owner of Seagull salon in New York. She writes art reviews regularly for the New Yorker and is a contributing editor for Artforum. She is a 2019 Creative Capital awardee and currently at work on a novel.