Melissa Anderson

Melissa Anderson

Feral vigor in a cult movie that influenced the riot-grrrl movement.

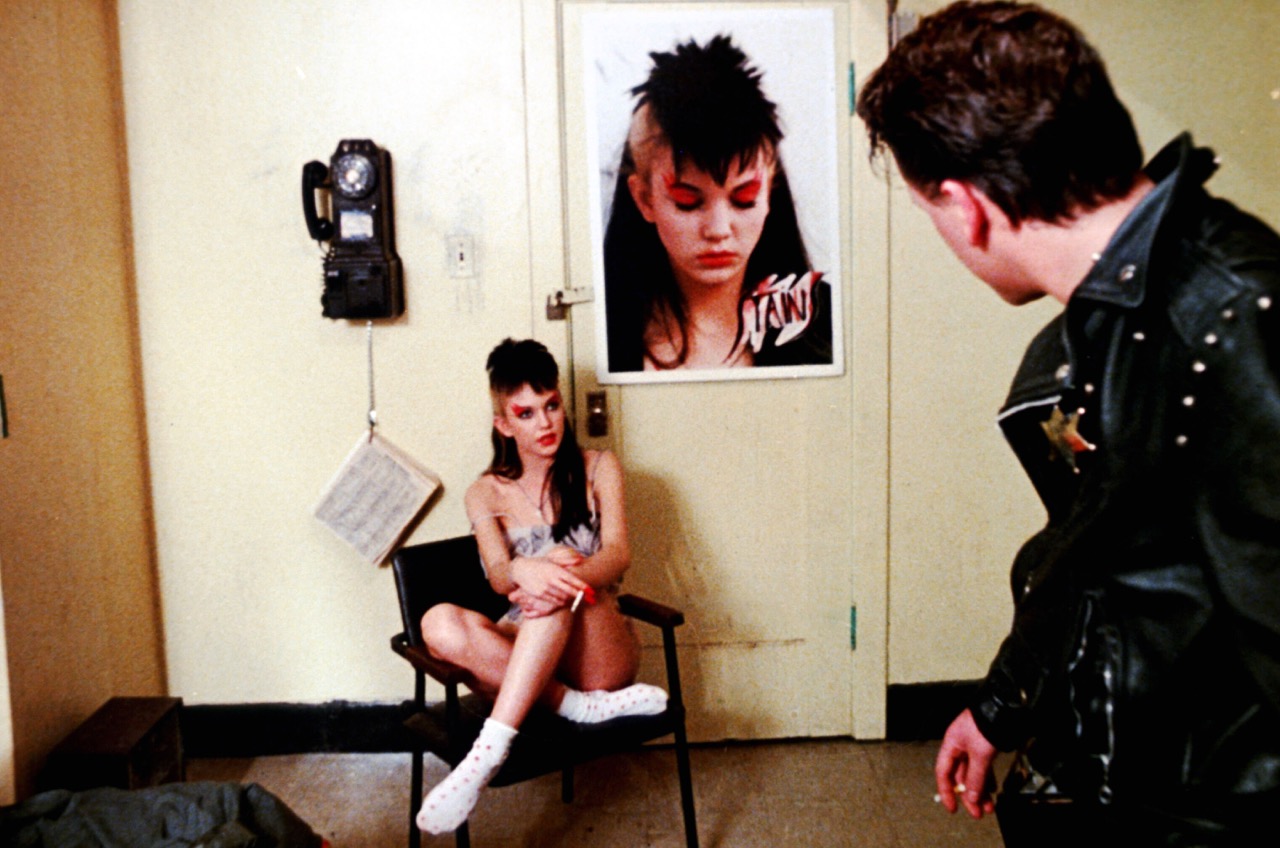

Marin Kanter as Tracy Burns, Diane Lane as Corinne Burns, and Laura Dern as Jessica McNeil in Ladies and Gentlemen the Fabulous Stains. Image courtesy Paramount Pictures.

Ladies and Gentlemen the Fabulous Stains, directed by Lou Adler, available to buy or rent on Amazon Prime, Google Play, iTunes, Vudu, and YouTube

• • •

Editor’s note: In light of the fact that most movie theaters around the country remain closed during the coronavirus pandemic, we have invited our contributors to revisit films that are particularly significant to them and that are easily found online.

• • •

Teenagers, like rock stars, thrive on paradox and self-dramatization. Long a cult object, Ladies and Gentlemen the Fabulous Stains (1982), about an adolescent-girl punk trio, boasts a supremely talented mythologizer at its center. “We’re the Stains, and we don’t put out,” snarls orphaned, penniless Corinne Burns (Diane Lane, fifteen at the time of filming and wildly charismatic), the lead singer of the DIY band, at one of its first gigs. Soon to become the group’s catchphrase, the declaration seems incongruous with its speaker, whose provocative stage outfit consists of a cherry-red see-through blouse, black bikini briefs, and fishnet stockings. To a pious TV reporter, Corinne explains why the slogan isn’t a contradiction: “It means don’t get screwed. Don’t be a jerk. Don’t get had.”

Diane Lane as Corinne Burns in Ladies and Gentlemen the Fabulous Stains. Image courtesy Paramount Pictures.

Corinne’s inconsistencies play out in a film that abounds with them, tensions and discrepancies that likely reflect the conflicting visions of its makers but that take nothing away from the movie’s feral vigor. Ladies and Gentlemen the Fabulous Stains is the second—and final—movie directed by rock impresario Lou Adler; his first was the Cheech and Chong vehicle Up in Smoke (1978). Stains was written by Nancy Dowd (here using the pseudonym Rob Morton), who had recently won an Oscar for her work on the screenplay for Coming Home (1978), the Jane Fonda–starring marital melodrama set during the Vietnam War. Dowd has said her Stains script was inspired by her first Ramones concert; she approached Caroline Coon, who chronicled the UK’s punk scene for Melody Maker and briefly managed the Clash, about consulting on the screenplay. In an interview last year with NPR, Coon stated that the script’s original ending, with the Stains triumphing in England, was ultimately nixed by Adler, who let the movie languish for two years after filming was completed before adding a coda of the (much visibly older) bandmates achieving MTV-anointed success.

In their early conversations about the script, Coon mentioned to Dowd that feminism would surely have a salutary influence on punk, a belief borne out, at the very least, by gender representation then: the London-based X-Ray Spex, for instance, was fronted by Poly Styrene, née Marianne Elliott-Said, who once famously proclaimed, on the quintet’s best-known track, “Some people think little girls should be seen and not heard / But I think oh bondage, up yours!” Stateside, the Runaways had charted in 1976 with “Cherry Bomb,” their sexed-up fuck-you anthem, cowritten by Joan Jett and sung by Cherie Currie.

The Stains, rounded out by Corinne’s sister, Tracy (Marin Kanter), and their cousin Jessica (Laura Dern, who turned thirteen during the shoot), prove to be magpies in their style and sensibility. At the band’s debut performance—only their fourth time playing together—Tracy (lead guitar) and Jessica (bass) are dressed in formfitting leather jumpsuits that recall one of Currie’s ensembles. Corinne—bundled up in an oversize wool trench coat (underneath is that risqué costume described above) and red beret (soon to be tossed off to reveal a two-tone mullet), and sporting the elaborate maquillage favored by British punk demigoddess Jordan Mooney—stares down the bored audience while launching into the Stains’ nihilist ditty “Waste of Time.” Enraged by the spectators’ indifference, she accosts a woman sitting up front with her smug boyfriend: “These guys laugh at you. They’ve got such big plans for the world but they don’t include us. So what does that make you? Just another girl lining up to die.”

Ladies and Gentlemen the Fabulous Stains. Image courtesy Paramount Pictures.

The tirade evinces Corinne’s gift for the gutting aperçu—and her media savvy. Her words begin to attract the attention of various local news outlets. After the bassist of the pathetic metal band that the Stains are on tour with dies of an overdose, she offers this as a requiem to a TV correspondent: “He was an old man in a young girl’s world.” (Later, she’ll deliver a pointedly gender-specific civic wish: “I think every citizen should be given a guitar on her sixteenth birthday.”) The young girls like what this prophetess has to say, showing up to Stains concerts as Corinne clones—a legion of skimpily dressed teens that Adler’s camera pans across a little too slowly.

Diane Lane as Corinne Burns and Ray Winstone as Billy in Ladies and Gentlemen the Fabulous Stains. Image courtesy Paramount Pictures.

Like many rock luminaries before her, Corinne flagrantly appropriates. The Stains audaciously cover “Professionals,” a track belonging to the group that the distaff trio opens for: the Looters, a UK quartet led by Ray Winstone’s Billy. (The rest of the Looters is made up of real-life punk icons: Steve Jones and Paul Cook of the Sex Pistols and Paul Simonon of the Clash.) The film is at its most disjointed in the final act, seeming to endorse Corinne’s comeuppance for her unslakable desire for fame, only to reward that drive with the closing music video for “Professionals.” (Which, with its dopey B-roll footage, perfectly mimics the aesthetic of then-nascent MTV.)

Marin Kanter as Tracy Burns, Diane Lane as Corinne Burns, and Laura Dern as Jessica McNeil in Ladies and Gentlemen the Fabulous Stains. Image courtesy Paramount Pictures.

Opening in just a few cinemas in the US in October 1982, Stains never had a proper theatrical release. It reached a wider audience a few years later, though, as one of the movies featured on USA Network’s Night Flight, the great small-screen showcase of arcana and oddities that aired on Fridays and Saturdays in the wee hours—which is when I, a teenager keeping vampire hours, first saw the film. Circulating in bootleg copies over the decades, Stains had a profound influence on bands like Bratmobile and other essential acts in riot grrrl, the genre that most successfully combined feminism and punk.

Corinne isn’t a stable signifier, yet she is played by someone who is unfailingly, preternaturally magnetic. Stains was not Lane’s first movie—she made her screen debut in A Little Romance, from 1979. But Adler’s film came out the year before the actress cemented her A-lister status, attained largely owing to several features she made with Francis Ford Coppola in the ’80s. During my most recent viewing of Ladies and Gentlemen the Fabulous Stains a few weeks ago, I thought often of this phenomenal line from a 2004 essay by George Toles on David Lynch’s Mulholland Drive: “The only earthly identity that might be strong enough to undo death is that of an actress on the verge of stardom.” Lane, in Adler’s movie, is just another girl lining up to live.

Melissa Anderson is the film editor of 4Columns.