Daniel Penny

Daniel Penny

In a maximalist online exhibition, new media artists pursue the GIF.

Screenshot of Well Now WTF? homepage.

Well Now WTF?, curated by Faith Holland, Lorna Mills, and Wade Wallerstein, presented by Silicon Valet, on view here

• • •

Curated by Wade Wallerstein, Faith Holland, and Lorna Mills, and designed by Kelani Nichole, the virtual exhibition Well Now WTF? focuses on the GIF—the simple moving-image format that has been a part of the visual language of the internet since 1987. Over 120 works were assembled in a matter of weeks after major US cities began their lockdowns, and the effect is dizzying. Slick computer-animated renderings of impossible geometries vibrate next to Boschian hellscapes of writhing naked bodies and malformed chimeras. Contemporary art stars like Ryan Trecartin share space with net art pioneers like Jan Robert Leegte, along with art-school students such as Sydney Shavers. The sick and the sickly sweet rub up against each other in a cacophony that, to me, feels a truer representation of the mediated age of COVID-19 than the daily ritual of Instagramming sourdough starter. Our mantra may be one of isolation, but online—where most of the action takes place these days—information and pixels mingle freely.

Screenshot of “Stay Home and Masturbate” room in Well Now WTF?. Featured: artwork by Adrienne Crossman.

In its most basic form, the GIF is an animated object that moves within a frame, wiggles against a still background, or loops endlessly. Formally, it is a cousin of the silent film strip or the rotoscope, marked by a tension between movement and stillness, progression and repetition. Typically, we encounter GIFs as part of everyday life on the internet, not just as media we consume, but as disposable readymades that we modify and circulate as a mode of communication. (The exhibit is sponsored by GIPHY, a popular GIF-sharing tool.) But as critic and art historian Domenico Quaranta outlines in his survey Beyond New Media Art, many artists and programmers have been pushing the boundaries of this format for decades. Well Now WTF? offers a compelling testament to the GIF’s varying aesthetic and conceptual possibilities.

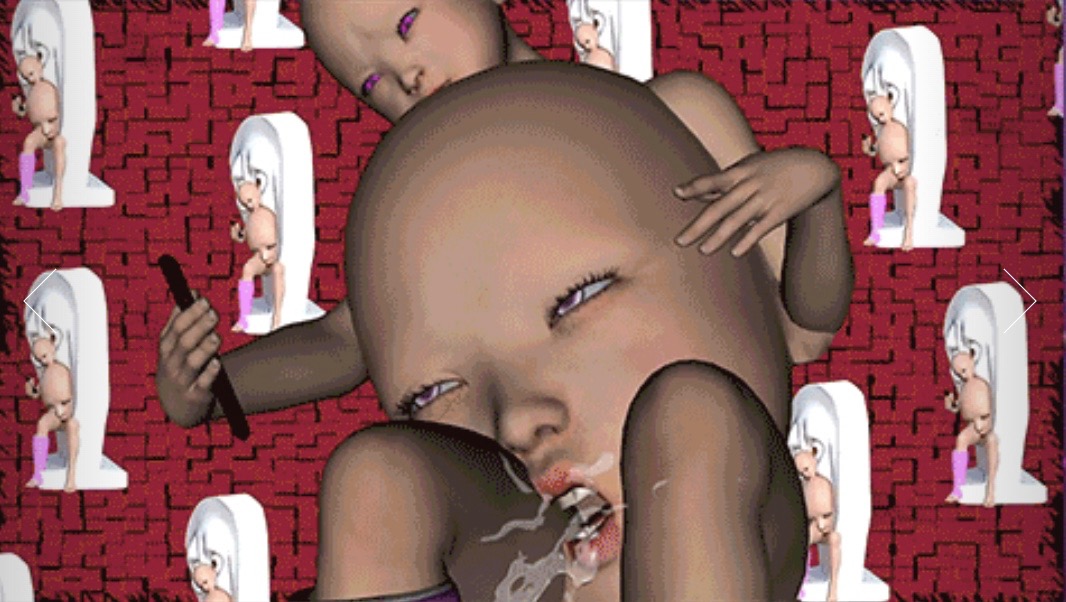

Screenshot of artwork by Wednesday Kim in Well Now WTF?.

Visitors enter the show through a home screen, which opens onto a thumbnail gallery of “rooms” populated with around a dozen moving images each. Click through to see everything in the room or jump around using the top menu. A prevailing language of the grotesque, absurd, and abject connects much of the art on view. Wednesday Kim’s 3D animation is particularly unnerving, a grid of dolls whose stomachs consist of even larger dolls’ heads that puke on repeat. Other contributions, like Petra Cortright’s, take a more stripped-down approach: her piece consists solely of black-and-white text arranged into a haunting image of an altar and cross. Some works were made for the show, while others had been created before COVID and were solicited by the curators. The most successful GIFs understand the conventions of the format—the frenetic pace, the flat perspective—and explode them. In this vein, Hannah Neckel’s 666 is a bubblegum landscape layered with twisting chains, flashing numbers, a warped 3D interior, and a flat, web-1.0 smiley face hopping down a set of stairs and then flipping over to reveal a crudely drawn backside.

Screenshot of artwork by Hannah Neckel in Well Now WTF?.

Well Now WTF? is hardly the first online exhibition of new media art, but it is a very well-timed one. In his exhibit essay, Wallerstein positions the pieces on display as not “directly responding to the global devastation wrought by COVID-19,” but it is impossible to view them without this grim filter. Many of the GIFs, such as Faith Holland’s luminous, layered hands scrubbing themselves, or Geoffrey Pugen’s collage of germ imagery and ’80s kitsch, directly thematize the virus—and the titles of the individual rooms (“The Clean Room” or “Wash Your Fucking Hands”) frame the more oblique works in terms of the pandemic. In general, the groupings follow an intuitive logic, with some pieces linked by a mood, e.g., quarantine horniness in “Stay Home and Masturbate,” while others address concerns more directly connected to COVID-19’s effect on the art world, like “So Sad Because the Art Fairs Were Cancelled.” A standout GIF from this room is Anthony Antonellis’s Graduation, in which school diplomas appear on computer screens in a never-ending assembly line—a trenchant critique of the way art schools continue to churn out debt-laden graduates with few opportunities for employment.

Screenshot of artwork by Anthony Antonellis in Well Now WTF?.

As a rule, the aesthetics and curatorial approach in Well Now WTF? are maximalist—and since the show first opened, it has only grown larger, with new batches of GIFs and videos. But this expansiveness means the show is not uniformly compelling. The weaker pieces tend to uncritically deploy familiar tropes of the GIF or YouTube video: a 360-degree rotation, a liquid object that dissolves and reforms itself, a zany clip that boomerangs an obvious action back and forth. Despite this overabundance, the curators seem unlikely to make cuts to a show that is as much a community space as an art show. One of the exhibit’s more interesting innovations is its use of Twitch, a popular streaming and chat platform for gamers, through which visitors can discuss the work, watch live stream lectures with visiting artists and critics, or take part in workshops.

Well Now WTF? is driven by the question of belonging. For decades, new media art and its progeny (net art, digital art, post-media art, etc.) have existed on the periphery of the fine art world, in part because most of the work doesn’t fit within the established protocols of the contemporary art market: it is immaterial, infinitely reproducible, and dependent on technologies that are constantly threatened with obsolescence. As a consequence, new media art has proliferated in its own ecosystem of technology expos, chatrooms, and social media platforms—or has been collected by forward-thinking institutions, like the New Museum. More than offering a way to “be alone, together,” as Wallerstein writes in his exhibition essay, the show gathers an international and intergenerational community of new media artists and inserts their work back into the center of art discourse. “Instead of jumping on the net art revival bandwagon,” writes Wallerstein, “Well Now WTF? is dedicated as a net art reclamation.”

Wallerstein’s essay points to the curators’ struggle with whether to position the exhibit as a part of or in opposition to those institutions and tastemakers who have only now bothered to pay attention to what it means to look at art on the internet. Under lockdown, established galleries like David Zwirner and Pace have been experimenting with online exhibitions, but viewing photographs or videos of physical works on a laptop or smartphone feels like a shadow of the in-person experience. By comparison, the screen is the natural home of the GIFs and short videos on view in Well Now WTF?—art that is not merely on the internet, but of it. Though the show sometimes buckles under its own weight, it manages to make a seemingly throwaway digital medium feel like an authentic expression of our plugged-in lives at a time when so much else can feel unreal.

Daniel Penny writes about art and culture at the New Yorker, the Paris Review, GQ, Boston Review, frieze, and elsewhere. He teaches writing and visual culture at Parsons School of Design.