Melissa Anderson

Melissa Anderson

A young table-tennis champ careens and crashes through an obstacle course of chaos and catastrophes in Josh Safdie’s new film.

Timothée Chalamet as Marty Mauser in Marty Supreme. Courtesy A24.

Marty Supreme, directed by Josh Safdie,

opens in theaters December 25, 2025

• • •

What makes Marty Mauser run? What doesn’t make Marty Mauser run? Played by a de-glammed Timothée Chalamet, the twenty-three-year-old cocky nudnik, hustler, and aspiring table-tennis world champ is perpetually in motion, in transit, on the go, on the prowl, on the lam. Too often, though, this constantly kinetic film spins out, running aground and out of ideas.

Tyler Okonma as Wally (far left) and Timothée Chalamet as Marty Mauser (right, background) in Marty Supreme. Courtesy A24.

Marty Supreme is the first solo directorial effort by Josh Safdie since the announcement that he and his brother and collaborator, Benny—who last worked together on the frantic Uncut Gems (2019)—would be pursuing their own, individual projects (it is unclear whether the hiatus is temporary or permanent). October saw the release of Benny’s The Smashing Machine, a wan biopic of the MMA star Mark Kerr, played by Dwayne Johnson, buried under facial prosthetics. Curiously, Josh’s movie shares some superficial similarities with his sibling’s. While not a dramatization of an actual personage’s life, Marty Supreme is nonetheless loosely inspired by the real-life table-tennis legend Marty Reisman, who, like Chalamet’s character, is a Lower East Side Jew born in the early years of the Depression. Both Mark Kerr and Marty Mauser are competitors in less-heralded sports in the US, and each has a crucial match in Japan. Yet The Smashing Machine, which Benny also wrote, pokily adheres to the standard highs-and-lows arc of the filmed biography. In contrast, Marty Supreme—coscripted by Josh and Ronald Bronstein (who first began working with the Safdies on 2009’s Daddy Longlegs)—careens and crashes at breakneck speed, its pinwheeling energy far surpassing the entropy and velocity of the brothers’ jointly helmed films, each an exercise in escalating chaos.

Timothée Chalamet as Marty Mauser (center right) in Marty Supreme. Courtesy A24.

The first minutes of Marty Supreme, which spans 1952 to ’53, instantly immerse us in the mayhem. As a short-term employee at an LES shoe store owned by his uncle Murray (Larry “Ratso” Sloman), Marty is mid-spiel, upselling a matronly customer. Commerce is quickly abandoned for coitus, as Marty and Rachel (Odessa A’zion), his friend and tenement neighbor since childhood, rut in the stockroom. While they fuck, Marty yaks on about his imminent trip to London for an international table-tennis competition. His nattering is soon drowned out by the ’80s synth-pop ballad “Forever Young,” one of many songs from that decade on the soundtrack, the aural anachronisms adding to the overall anarchy. During the opening credits, the screen fills with footage of a sperm fertilizing an egg, the ovum segueing to a ping-pong ball, which Marty smashes almost as ardently as he did Rachel.

Kevin O’Leary as Milton Rockwell (center) and Timothée Chalamet as Marty Mauser (far right) in Marty Supreme. Courtesy A24.

The inconvenience of Rachel’s pregnancy—for starters, she’s married to another tenement resident—is just one of a multitude of obstacles, mostly self-inflicted, that Marty must contend with in his quest for table-tennis glory. These also include, but are not limited to, paying a $1,500 fine incurred for ditching the spartan player barracks in London and installing himself in a suite at the Ritz during his tournament; winning back the sponsorship of Milton Rockwell (Kevin O’Leary), a pen magnate whom Marty insulted and whom the paddle-whiz is cuckolding, enjoying intermittent assignations with the tycoon’s wife, retired screen legend Kay Stone (an excellent, dolorous Gwyneth Paltrow); fleeing the cops, paid by Murray to nab his nephew; and reuniting, for what he’s certain will be a handsome reward, a lowlife named Ezra Mishkin (Abel Ferrara, godhead-auteur of scuzzy Gotham and a lodestar for the Safdies) with his dog after Marty injured both man and beast when the fleabag bathtub he was soaking in crashed into their lodging below.

Abel Ferrara as Ezra Mishkin in Marty Supreme. Courtesy A24.

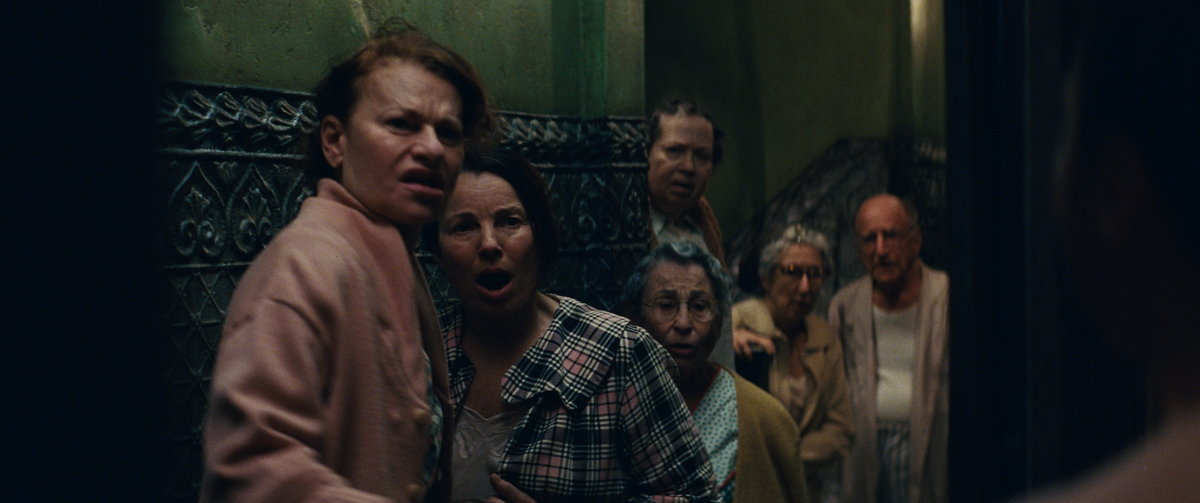

The catalyzing catastrophes for the scenarios above take up the film’s first hour. Ninety minutes remain. Still to come: a mob of New Jersey yokels out for revenge, a conflagration, two shoot-outs, cunnilingus in Central Park, a trip to the ER, a showdown in Tokyo. Perhaps the nonstop tumult wouldn’t aggravate so much if there weren’t so many missed opportunities. Spiky comedienne Fran Drescher, as Marty’s manipulative, hypochondriac mom, Rebecca, has but a handful of lines. Even more distressing is seeing Sandra Bernhard, playing Judy, another Mauser neighbor and Rebecca’s pal, pop up on-screen and just as quickly disappear. Similar to Marty, Bernhard’s Masha—a spectacularly deranged superfan of a Johnny Carson–like TV host in The King of Comedy, Martin Scorsese’s mordant satire from 1983—was an unparalleled yammerer given to florid arias of verbal aggression. Why waste the talents of this brilliant word-weaponizer on a nearly mute character? Why couldn’t Judy challenge Marty’s supremacy?

Sandra Bernhard as Judy (far left) and Fran Drescher as Rebecca Mauser (second from left) in Marty Supreme. Courtesy A24.

Why couldn’t anyone? Marty may be humiliated at one point by Rockwell, a man much richer and more powerful than he is, but the degradation of the stripling only makes the business baron appear more villainous—and Marty more virtuous. His only real opponent is the serene Japanese ping-pong player Koto Endo (Koto Kawaguchi, a bona fide table-tennis star), who bests Marty at the London tourney, a loss the New Yorker is determined to reverse at an expo in Japan. Chalamet, as has been widely reported, spent years practicing the sport, and seeing his spindly, windmilling limbs as he serves, volleys, hotdogs, and races around the court, grunting as loudly as Rafael Nadal at the French Open, provides kicky thrills. And the actor—his pretty punim here desecrated by a monobrow that looks like the headbutting of two large caterpillars, a wispy mustache, pimples, and pockmarks—clearly savors his character’s titanic self-regard. Marty seems to speak only in declarative sentences, typically beginning with “I,” delivered as incontrovertible fact. These proclamations range from the benignly bombastic (“I’m uniquely positioned to be the face of the sport in the United States”) to the obscenely offensive (“I’m gonna do to Kletzki”—a Hungarian rival—“what Auschwitz couldn’t: I’m gonna finish the job”) to the cruelly caddish (“I have a purpose. You don’t,” he says to Rachel).

Timothée Chalamet as Marty Mauser in Marty Supreme. Courtesy A24.

While this exasperating, sometimes exhilarating movie finds Josh Safdie, severed from his brother’s creative input, indulging in, to increasingly diminishing returns, more of the wheel-spinning havoc that characterizes his work with Benny, Marty Supreme also marks an ignominious first in the Safdie cosmos: a shamelessly sappy ending, with the egomaniac protagonist somehow transformed into a caring, doting, weeping man. The conclusion is no less than a Supreme sacrifice.

Melissa Anderson is the film editor of 4Columns and the author of a monograph on David Lynch’s Inland Empire from Fireflies Press. A collection of her film criticism, The Hunger, has just been published by Film Desk Books.