Melissa Anderson

Melissa Anderson

A 1960s faux documentary explores the pitfalls of pop star worship.

Paul Jones as Steven Shorter in Privilege. © 1998 Universal City Studios, Inc.

Privilege, directed by Peter Watkins, now available on Blu-ray from

Kino Lorber

• • •

In a 1966 interview, John Lennon declared that the Beatles were “more popular than Jesus.” Two years later, the Rolling Stones recorded “Sympathy for the Devil,” a sulfurous anthem in which Mick Jagger, singing in the first person, would appear to be the Prince of Darkness himself. The appeal of the pop culture that emerged from the UK during the ’60s—particularly of these two bands—was so pervasive that identifying with Christ or the Antichrist wouldn’t ring as hyperbole.

Born in 1935, the uncompromising British filmmaker Peter Watkins found something sinister in this worship of rock musicians—not on religious but ideological grounds. Shot in London and Birmingham and set “in the near future,” Privilege (1967), Watkins’s first feature-length movie intended solely for theatrical release, is structured, like nearly all of his projects, as a fake documentary. At the center of this faux nonfiction is Steven Shorter (Paul Jones), “the most desperately loved entertainer in the world,” per the off-screen narrator (uncredited, the orotund voice is Watkins’s own).

Paul Jones as Steven Shorter in Privilege. © 1998 Universal City Studios, Inc.

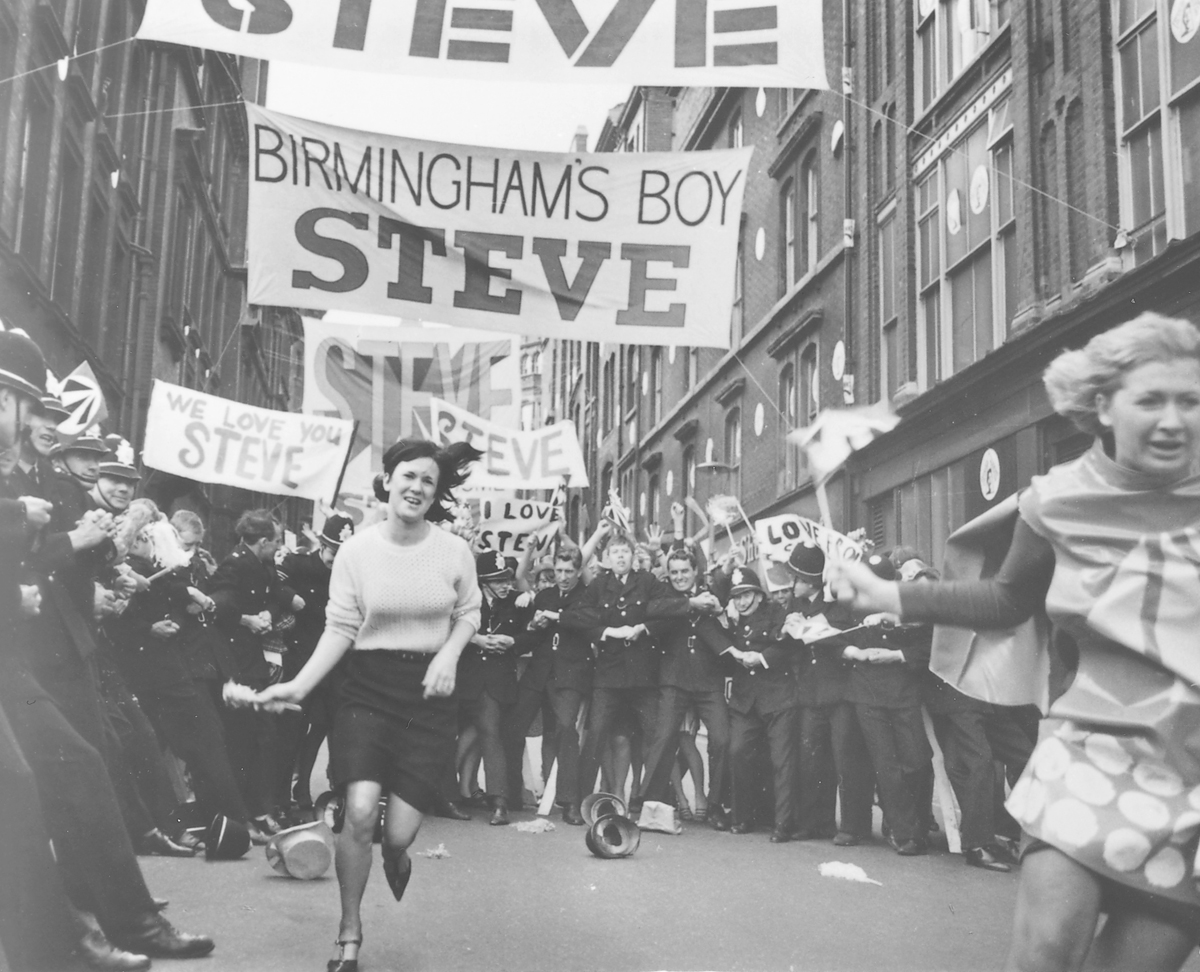

Steven’s Sadean stage act—in which the singer, locked in a cage, croons “Free Me,” and, once unpenned, battles against bobbies quick to use truncheons—has been designed to purge its spectators “of all the nervous tension caused by the state of the world.” After the pop idol concludes his show, audience members rush the podium to attack the cops—behavior condoned by the coalition UK government (the differences between Labour and Tory policies having become nonexistent) as a means to “divert the violence of youth” and keep them out of politics. Adolescent insurrectionary impulses, instead of being directed at toppling sclerotic, inequitable institutions, can now be slaked by witnessing and participating in grotesque, state-sanctioned ritual. (Watkins, along with the American novelist Norman Bogner, adapted the script for Privilege from an original screenplay by Johnny Speight, a prolific British sitcom writer.)

Paul Jones as Steven Shorter in Privilege. © 1998 Universal City Studios, Inc.

Unabashedly didactic, at times acutely moralistic, Privilege nonetheless remains hard to shake. Formally, the film ensorcells, re-creating, but not too fussily, the key stylistic elements of cinema verité: straight-to-camera interviews, handheld camerawork, a sense of action caught on the fly. Watkins first deployed this mimicry of direct-cinema techniques in the two earliest docufictions he helmed for the BBC, where he had begun working in the early ’60s: Culloden (1964), a depiction of the 1746 battle in which the British army quashed a Scottish Jacobite uprising, and The War Game (1965), which vividly imagines a nuclear attack in the UK—so vividly, in fact, that the Beeb banned it from airing on television for twenty years. Released in cinemas in 1966, The War Game, despite being a speculative fiction, won the Academy Award for Best Documentary in 1967. (Watkins would return to the topic of anticipating nuclear catastrophe in his transcontinental, fourteen-hour epic The Journey from 1987.) That industry accolade led to Universal Pictures’ backing of Privilege, the sole instance of a Hollywood studio distributing a work by Watkins.

Still from Privilege. © 1998 Universal City Studios, Inc.

However captivating the nonfiction simulation in Privilege may be, the fiction in this pseudo-doc announces itself clearly—not only via the youthquaking set and costume design, each a riot of blazing primary colors, but also thanks to the poignantly stilted acting of Privilege’s two top-billed stars, each making their screen debuts. From 1962 to 1966, Jones was the lead singer of Manfred Mann, a C-list British Invasion group (their biggest hit was 1964’s supremely irritating “Do Wah Diddy Diddy”), and had just embarked on a solo career by the time Privilege began filming. Steven Shorter finds emotional succor in Vanessa, an artist commissioned by the Ministry of Culture to paint the idol’s portrait; she is played by Jean Shrimpton, considered the world’s first supermodel and the epitome of Swinging London fabulousness. The vacancy of these celebrities onscreen—never again would Watkins, who preferred casting everyday citizens and unknown actors, collaborate with such high-profile personages—oddly works in Privilege’s favor, underscoring the film’s (perhaps too obvious) point about fame’s anesthetizing effect.

Jean Shrimpton as Vanessa and Paul Jones as Steven Shorter in Privilege. © 1998 Universal City Studios, Inc.

Although Steven is an avatar of then-ultrahip Carnaby Street chic—replete with mod mop top and slim-fitting suits consisting of mandarin-collared tunics and blazers—he was in part informed by a very square teen heartthrob from earlier in the decade and from the other side of the Atlantic. Watkins has been outspoken in his admiration for Lonely Boy, a short 1962 cinema verité profile of Paul Anka, not yet twenty at the time of filming and a top-ten hitmaker with such syrupy ballads as the eponymous song (from 1959) and 1960’s “Puppy Love.” Some lines from Lonely Boy are repurposed almost verbatim in Privilege, namely this chilling declaration from Alvin (Mark London), Steven’s crocodilian press agent: “He does not belong to himself. He belongs to the world. Therefore, he has no rights to himself.”

Hollowed out of all personhood, the singer becomes a ubiquitous nationalist brand. Three hundred Steven Shorter discotheques are built “to spread happiness in Britain”; the same number of “Steve Dream Palaces” are constructed to keep people “buying British.” Possessed of highly signifying initials, Steven Shorter will soon be performing—his arms outstretched in supplication and his figure backlit by an enormous megawatted cross—before nearly fifty thousand people at an evening outdoor evangelical rally seemingly art directed by Leni Riefenstahl.

Paul Jones as Steven Shorter in Privilege. © 1998 Universal City Studios, Inc.

At that moment, just when Watkins’s society-of-the-spectacle hectoring seemed too much, I was brought up short (Shorter?) by that scene’s eerie resemblance to another (real) outdoor nighttime concert that would occur three years after this fake one was shot: the Rolling Stones at California’s Altamont Speedway on December 6, 1969, a performance that ended in a spectator’s killing while the band played “Under My Thumb,” a blood-soaked crypto–Black Mass captured in the documentary Gimme Shelter (1970), by the direct-cinema eminences Albert and David Maysles and Charlotte Zwerin.

Privilege played out of competition at Cannes in 1967; that year, the festival’s top prize would go to Michelangelo Antonioni’s Blow-Up, another film animated by the Swinging London scene and another attempt to comment, however wanly, on the emptiness of mass media. Antonioni’s movie has long been considered canonical; Watkins’s is barely recalled. Cool and removed, Blow-Up has always struck me as dilettantish and gossamer-thin. Fiery, impassioned, imperfect, Privilege may occasionally exasperate, but it never postures.

Melissa Anderson is the film editor of 4Columns. Her book on David Lynch’s Inland Empire is available from Fireflies Press as part of its Decadent Editions series.