Will Noah

Will Noah

The private lives of poets: Alejandro Zambra writes a

multigenerational saga.

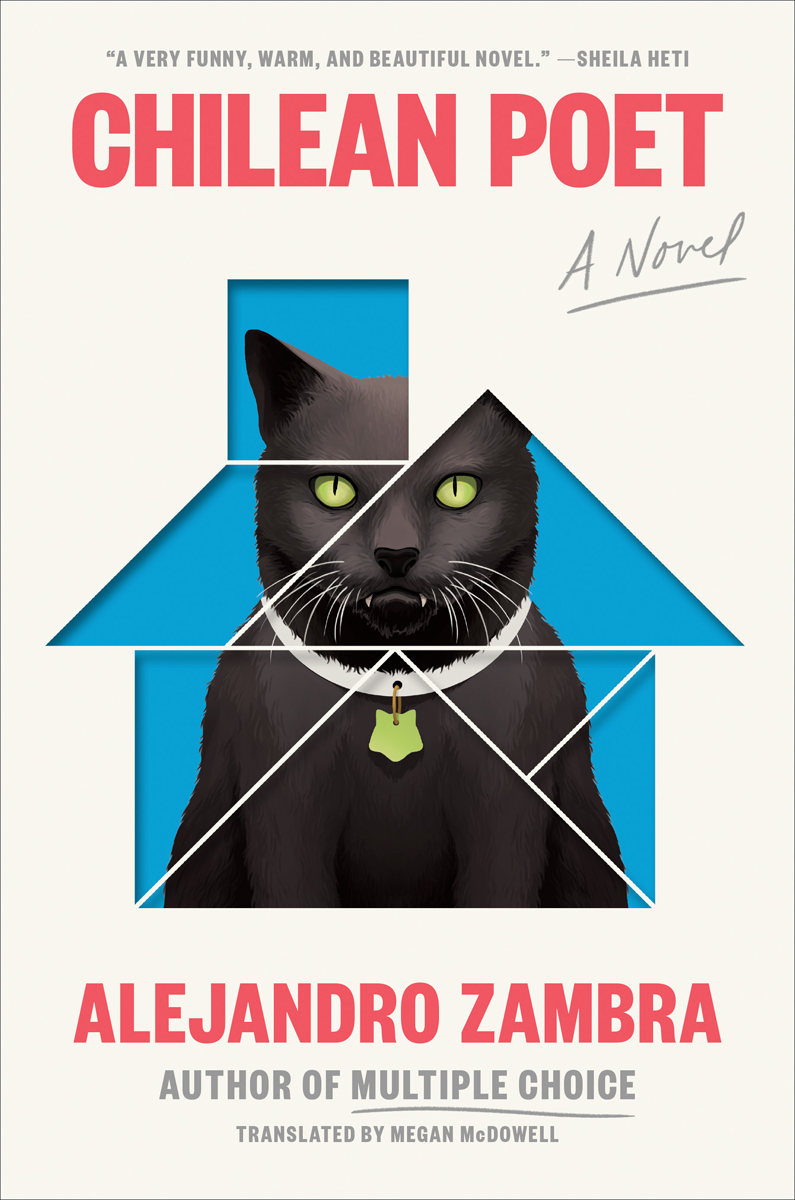

Chilean Poet, by Alejandro Zambra, translated by Megan McDowell, Viking, 358 pages, $27

• • •

Up until now, Alejandro Zambra’s writing has erred on the side of silence. The Chilean author’s early novels, not much thicker than chapbooks, radiate with potential in the same way that youth does: neither knows what comes next. “I didn’t want to write a novel,” Zambra later said of his first, Bonsai, “but rather the summary of a novel. A bonsai of a novel . . . Instead of adding, I subtracted: I wrote ten lines and erased eight; I wrote ten pages and erased nine.” He was thirty when the book appeared in 2006, but it reads as the work of an even younger writer. When it comes to the mixed-up effusion of erotic and intellectual life kicking off at once, his little debut knows everything there is to know. Its lovers believe that “life only had purpose if you found someone who changed it, who destroyed your life.” But what happens when you go on living?

Since Bonsai, each of Zambra’s subsequent novellas—The Private Lives of Trees (2007), Ways of Going Home (2011)—has been more confident than the last, its voice further refined (his regular translator Megan McDowell has mastered the predominant tone of droll melancholy right along with him). But even better are the short-form collections that followed them: My Documents (2013) is a near-perfect suite of stories circling themes of family, fiction, and computers; Multiple Choice (2014) wrings humor and disquieting insight from the gimmick of imitating a standardized test. It’s easy to imagine Zambra continuing in this vein, as a miniature artist. But despite his apparent affinity for small books, he’s confessed in the essay collection Not to Read (2010) that he loves “long novels, the ones we reserve for the first flu of the year, the ones that oblige us to invent the first flu of the year so that we can stay home reading them.” His latest book, Chilean Poet, is not quite a doorstopper, but it’s certainly his longest yet, at three-hundred-fifty pages; and its ampleness of vision far exceeds its moderate girth. The oldest of this novel’s main characters may not have aged out of their thirties by the time it ends, but they’ve lived more of their lives under our gaze than Zambra has ever tried to show us before.

Chilean Poet returns to Bonsai’s theme of a young writer’s awakening, but attains its depth by doubling the portrait and tracing both characters through time. Poet #1 is Gonzalo, a familiar author-surrogate type: socially awkward, romantically devoted, endearingly bibliophilic, occasionally impulsive and abrasive. He’s introduced as a teenager fumbling his way toward sex with his first love, Carla. She dumps him, then reappears nine years later, now a single mother. Gonzalo moves in with her and her six-year-old son, Vicente, and they form a happy trifecta as poetry fades into the background. Here the romance of family drowns out that of literature, and Zambra locates a groove of mundane reverie, where narrative cools to happy stasis: “They always smoked in the front yard. They always replaced the burned-out light bulbs and the remote control batteries immediately . . . They never defragged the hard drive. They never cleared the leaves from the gutters when they should. They never fell asleep with the TV on.”

This paradise isn’t built to last, though, and the trust between Gonzalo and Carla eventually breaks down. Poet #1 exits the scene and moves to New York, where he gives up on writing and settles into an academic career. The action jumps ahead several years so that Vicente, now eighteen, can assume the role of Poet #2. He’s joined by another protagonist, an American freelance journalist named Pru, who decides to write about Chile’s poetry scene after meeting Vicente. “We’re going to discover a bunch of savage detectives,” Pru’s editor says by way of encouragement, invoking Roberto Bolaño, many a literate gringo’s reductive point of reference for the country’s literature. Zambra accepts the lineage with resigned irony: “I am a Chilean novelist,” his occasionally intrusive third-person narrator sums up, “and we Chilean novelists write novels about Chilean poets.” Pru’s interviews with a succession of showboating, machista avant-garde poets—with a few embattled women, Indigenous writers, and respectfully rendered real authors thrown in—thus form Zambra’s rendition of a Nazi Literature in the Americas–style literary encyclopedia.

There’s slack in this section of the novel, with the affection it indulges on its motley versifiers. But it also invokes a national theme, justifying the title: Chile is the country of Neruda and Mistral and Nicanor Parra, the final poet whom Pru visits. “How do the current Chilean poets dialogue with that legacy?” Pru’s editor asks her, with the crude abstraction of editors. “What is it like to be a poet in a country where apparently poetry is the only good thing?” For Zambra’s characters, a literary lineage is easier to cling to than a real one. All too often, their parents are tainted by the not-so-good things about Chile, particularly their roles as victims or beneficiaries or bystanders during Pinochet’s dictatorship. This context, underlined heavily in Ways of Going Home, is worn lightly in Chilean Poet, where the old guard’s bad parenting is personified by Gonzalo’s grandfather, a serial procreator he refers to as “the lech.” But the backdrop lends poignancy to the frenzied nest-building in all of Zambra’s books: his anxious affection for domestic bric-a-brac, routine, cats, steady partnered sex, everyday technology, bookshelves, the puzzling logic of children’s speech. His Chile is a place where the promise of middle-class happiness is always thwarted, where bonds between lovers and parents and children are forever fraying.

In the course of Pru’s interviews, the (real) poet Rosabetty Muñoz tells her about palafitos, a type of house built on stilts. “If there’s a breakup,” she notes, “one person can take the house and the other keeps the land.” The image of a home that’s built to be disassembled recurs in the form of a tangram that Gonzalo recalls buying and arranging as a house on the family fridge. But separation was never the plan for him and Carla and Vicente; looking back on photos from their time together, he sees a “blind and audacious wager on a future that is compatible with the present.” The novel’s denouement—in which it recovers much of its emotional heft—brings Gonzalo back to Chile, where he attempts to rebuild a relationship with Vicente years after that wager has failed.

A generational drama comes into focus here: in the past, authoritarian and absent fathers; in the future, innocence and promise, embodied by sweet Vicente. The latter, who looks up to student leaders like Camila Vallejo and Gabriel Boric (now president-elect), belongs to the bold, untested wave of young Chileans who would take to the streets in 2019 and demand a new constitution. Gonzalo was born too early for all that, stuck between past and future. Zambra wrote in a recent essay that, after he and his peers failed to do so, “Gabriel Boric’s generation, the generation of our little brothers, did kill the father. They formed their own parties and refused to take on our traumas. They deserve our respect, our affection, and our gratitude.” Still, Zambra has learned to live with his uneasy inheritance: “My father and I won’t ever stop speaking to each other. It’s good to know that.” Chilean Poet ends with such a truce, as Vicente reads Gonzalo his poems and tries to decide if he can forgive him. Maybe the future will bring a decisive break, but growing up means tempering disappointment with reconciliation.

Will Noah is a writer and translator based in Mexico City. His work has appeared in the Baffler, BOMB, n+1, and the New York Review of Books, and he is a member of the Criterion Collection’s editorial staff.