Melissa Anderson

Melissa Anderson

Bloodlust and obsession, carnage and castration: romance and heartbreak take on new meanings in the returning Anthology Film Archives series.

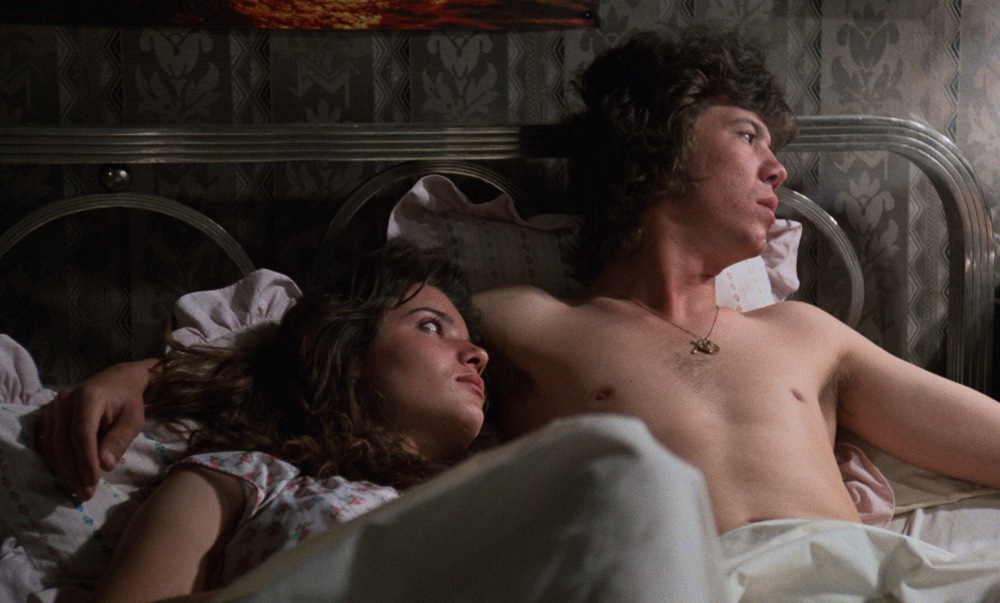

Berta Socuéllamos as Ángela and Jose Antonio Valdelomar González as Pablo in Deprisa, Deprisa. Courtesy Anthology Film Archives.

“Valentine’s Day Massacre 2026,” Anthology Film Archives, 32 Second Avenue, New York City, through February 22, 2026

• • •

A Whitman’s sampler laced with cyanide, Anthology’s “Valentine’s Day Massacre” series provides bracingly bleak programming to counteract one of the most abhorrent celebrations of the year. Launched in 2013, VDM originally consisted of Maurice Pialat’s We Won’t Grow Old Together (1972), a blistering, lightly fictionalized account of the filmmaker’s yearslong extramarital affair with a younger, working-class woman; and Albert Brooks’s Modern Romance (1981), a neurotic comedy exposing courtship as nothing more than a crazed cycle of extreme obsessive-compulsive disorder. In 2014, Andrzej Żuławski’s Possession (1981), a delirious, West Berlin–set dirge that tracks two spouses as they annihilate themselves—if not the entire planet—through binges of jealousy, rage, and despair, was added to the mix.

Through 2019, these three movies, unsparing in their depiction of love’s derangements and the emotional terrorism carried out by the couple, formed the core of VDM and were supplemented by a rotating roster of titles. (When I covered the series in 2017, Elaine May’s near-peerless comedies of humiliation, A New Leaf from 1971 and The Heartbreak Kid from ’72, filled out the bill.) Now, after a seven-year hiatus, VDM returns, with the main triad augmented by three selections from writer and video artist Payton McCarty-Simas. Only one film in this new trio could be said to focus on a dyad; the others more prominently showcase the unraveling of their unattached female protagonists. But all assay, as the original three do, the psychopathologies of heterosexuality.

Désirée Nosbusch as Simone (right) in Der Fan. Courtesy Anthology Film Archives.

In Eckhart Schmidt’s hallucinatory Der Fan (1982), teenage Simone (Désirée Nosbusch) is so consumed by her obsession with a dark-wave singer known only as R (Bodo Staiger) that she can do nothing but listen to his cold, brooding music and feverishly await a reply to one of her thousands of mash notes to him. The fixated adolescent hitchhikes from her hometown of Ulm to Munich to sit in the audience for her idol’s performance on a TV music show. R takes notice of Simone among the throngs of screaming teens, beds her, and then discards her—or tries to. In her own demented way, Simone annuls her rejection via lavishly Grand Guignol means. Schmidt’s film, which he adapted from his novel of the same name, can concuss with its clumsy symbolism: two runes that look suspiciously like the SS logo adorn Simone’s backpack; the one wall of her bedroom not dominated by posters of R is covered with a photo mural of thousands delivering a Nazi salute. When not equating pop-star adulation with Führer reverence, though, Der Fan fascinates with its icy elegance and dilatory sense of time—qualities shared by the music that has driven Simone to such an unhinged state.

Désirée Nosbusch as Simone in Der Fan. Courtesy Anthology Film Archives.

Like Simone, Molly (Millie Perkins), the mentally unwell main character in Matt Cimber’s queasy-making The Witch Who Came from the Sea (1976), also suffers from an overinvestment in mass culture. “You know how I love television!” she squalls to McPeak (Stafford Morgan), an actor she’s become besotted with after seeing him in a TV ad for razors. While they’re having an intimate moment, Molly wields the very instrument McPeak peddles to carve and castrate him; he is not the first quasi-celebrity to die mid-foreplay by her slicing. When not murdering her would-be lovers in the bedroom, Molly works as a barmaid at a Santa Monica dive, not too far from where she goes for long walks along the shore with her two adoring young nephews. The boys can’t get enough of her tales of her boat-captain father, supposedly swallowed up by the waves.

How Papa actually died will be revealed in the last of a series of sordid flashbacks depicting the abominable crimes he committed against Molly as a girl. I cannot lie: much of The Witch Who Came from the Sea is excruciating to sit through. (Yet at times—particularly during Molly’s littoral strolls with her nephews—beautiful to look at, thanks to the cinematography of an uncredited Dean Cundey, best known for his work with John Carpenter.) That wretchedness is further compounded by the circumstances surrounding the film’s origins. The script was written out of desperation by Robert Thom specifically for Perkins, his wife, as a way to pay down his enormous hospital bills at the time. The actress, who had made a high-profile screen debut as the lead in 1959’s The Diary of Anne Frank, could command a fee adequate to pay for her husband’s medical care, but the project mortified her—her distress evident in a performance that could charitably be described as robotic hysteria.

Berta Socuéllamos as Ángela (upper left) and cast in Deprisa, Deprisa. Courtesy Anthology Film Archives.

Despite her sociopathic behavior, Ángela (Berta Socuéllamos), one of a gang of miscreants in Carlos Saura’s scrappy Deprisa, Deprisa (1981), easily stands as the most psychologically sound antiheroine in the triptych curated by McCarty-Simas. Its title translating as “Faster, Faster,” Saura’s film captures the reckless velocity of these young Spanish criminals at the dawn of the post-Franco era. (They are all played by nonprofessional actors, most of whom would count Deprisa, Deprisa as their sole movie credit.) This impetuousness proves irresistible to Ángela, a waitress at a café, when she first meets Pablo (José Antonio Valdelomar), who’s stopped by the roadside tavern with a buddy, Meca (Jesús Arias Aranzueque), after they’ve hot-wired a car. Pledging undying love to her, Pablo is soon showing Ángela how to handle a gun. She, in male drag replete with adhesive mustache and fake stubble, advances from lookout to shooter as the cadre—their larcenous schemes now more ambitious—grows to include Sebas (José María Hervás Roldán).

Berta Socuéllamos as Ángela and Jose Antonio Valdelomar González as Pablo in Deprisa, Deprisa. Courtesy Anthology Film Archives.

“Can’t you see she’s out of control?” Sebas complains to Pablo about his lover after Ángela proves a little too trigger-happy. (IRL, Roldán and Socuéllamos married the year after Deprisa, Deprisa premiered.) Her bloodlust notwithstanding, she is the most sensible of her cronies, forgoing the smack the guys love to snort and convincing Pablo of the benefits of owning versus renting an apartment. After a bank heist ends in carnage, Ángela stuffs wads of bills into a duffel bag, walking unaccompanied into crepuscular light. This image—a woman alone, now free of any connection to any man—lingers as the most romantic one in a series devoted to the grievous harm wrought by coupledom and the ills of male worship.

Melissa Anderson is the film editor of 4Columns and the author of a monograph on David Lynch’s Inland Empire from Fireflies Press. A collection of her film criticism, The Hunger, is now available from Film Desk Books.