Melissa Anderson

Melissa Anderson

Rewatching the 1973 concert documentary.

A concert attendee in Wattstax. Image courtesy Wattstax.

Wattstax, directed by Mel Stuart, available to buy or rent on Google Play, iTunes, and YouTube

• • •

Editor’s note: In light of the fact that most movie theaters around the country remain closed during the coronavirus pandemic, we have invited our contributors to revisit films that are particularly significant to them and that are easily found online.

• • •

All dating to the Nixon era, a quartet of essential concert documentaries capture various rock-music idioms and vibes. D. A. Pennebaker’s exultant Monterey Pop (1968) chronicles the celebration that kicked off 1967’s Summer of Love. The epic length of Michael Wadleigh’s Woodstock (1970) reflects the behemoth sprawl of that boomer-defining, occasionally turgid “Aquarian Exposition.” The sepulchral Gimme Shelter, the infamous snuff rockumentary (also from 1970) by Albert and David Maysles and Charlotte Zwerin, records the disastrous Rolling Stones ’69 performance that ended with an attendee’s death at the hands of a Hells Angel. Released in 1973, Mel Stuart’s Wattstax, a film of the 1972 event of the same name—featuring an empyreal roster of soul, blues, R & B, and gospel artists on the Stax label—shares Monterey Pop’s ebullience. (Another link: Pennebaker’s movie includes a blazing set by Otis Redding, Stax’s greatest powerhouse at the time; the soul singer died, at age twenty-six, just six months after his transporting Monterey performance.) But unlike any of its predecessors, Wattstax is distinguished not only by ecstatic singing but by kinetic speaking.

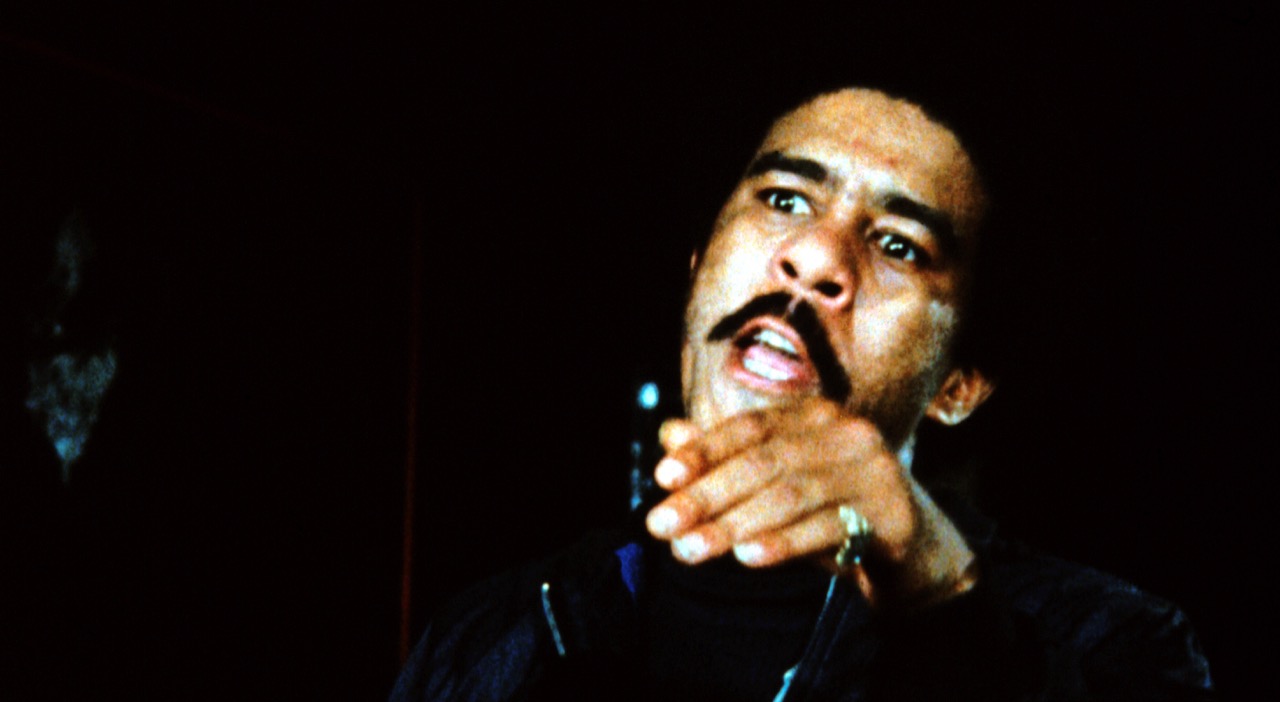

Richard Pryor in Wattstax. Image courtesy Wattstax.

Fittingly, Wattstax opens with one of the most dynamic talkers of the past fifty years: Richard Pryor. Solemn, his arms folded across his chest, the comedian provides some background on what we’re about to see—and listen to. “All of us have something to say. But some are never heard,” Pryor affirms, the camera slowly zooming tighter on his face. He continues, referring to the Watts Rebellion of August 11–16, 1965, an uprising catalyzed by, among several long-festering ills, an incident of police brutality: “Over seven years ago, the people of Watts stood together and demanded to be heard. On a Sunday, this past August, in the Los Angeles Coliseum, over one hundred thousand Black people came together to commemorate that moment in American history. For over six hours, the audience heard, felt, sang, danced, and shouted the living word in a soulful expression of the Black experience. This is a film of that experience and what some of the people have to say.”

Jesse Jackson and Isaac Hayes in Wattstax. Image courtesy Wattstax.

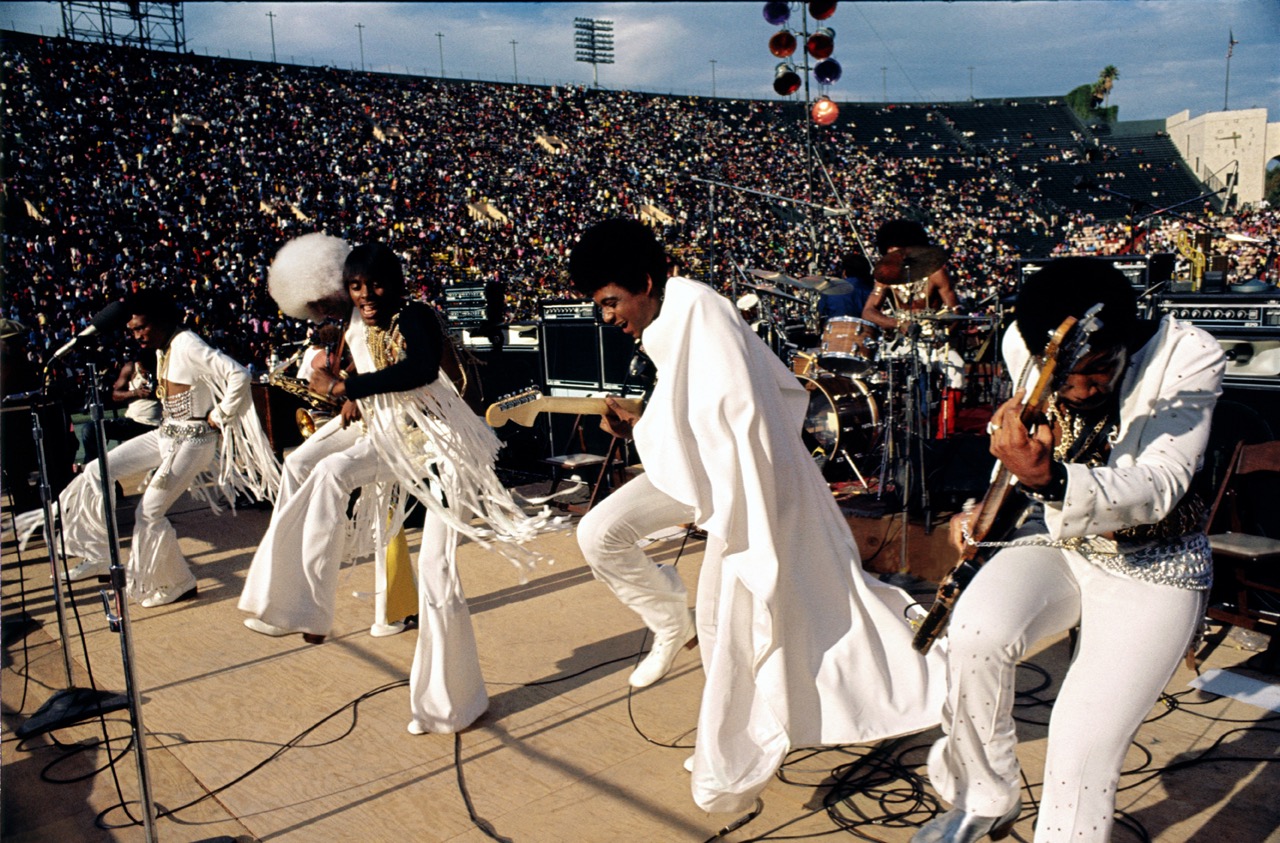

Wattstax includes a dozen phenomenal performances excerpted from the concert, held on August 20, 1972, the date that Isaac Hayes, the final act of the night, turned thirty; that milestone birthday helped determine when the gathering would take place. These dynamite segments—of, to name just a few highlights, Kim Weston, the Staple Singers, the Bar-Kays, Carla Thomas, and Rufus Thomas—are plaited with scenes of Black Angelenos conversing on a variety of topics and Pryor killing it with bits performed in a small nightclub. Verité footage of the South Los Angeles neighborhood is interspersed throughout: church fronts, Angela Davis murals, couples in love, kids at play, and, after Pryor’s intro, Simon Rodia’s kaleidoscopic Watts Towers, their majesty enhanced by the Dramatics’ “Whatcha See Is Whatcha Get” thundering on the soundtrack. (Wattstax also includes sequences featuring acts that were scheduled to play at the LA Coliseum but were cut owing to the event’s time constraints; the most transcendent of these episodes shows the Emotions singing the gospel standard “Peace Be Still” at a Baptist church in Watts.)

The Bar-Kays performing in Wattstax. Image courtesy Wattstax.

While unquestionably civic-minded—tickets to the concert were only one dollar, and profits went to various Watts organizations—the event was also a bid for brand expansion: the Memphis-based Stax Records, then co-owned by Al Bell, the label’s first prominent African American executive, was eager to raise its profile in Southern California. Bell and Larry Shaw—Stax’s African American creative and advertising director, who wanted the film “to become a mirror” of the Black community—asked documentary producer David Wolper, a veteran of National Geographic and Jacques Cousteau specials, to serve as executive producer of the concert movie. To direct Wattstax, Wolper brought in Stuart, who had helmed Willy Wonka and the Chocolate Factory (1971), which Wolper also produced. Although Stuart and Wolper were white, Stax insisted on a racially integrated camera crew; among Wattstax’s cinematographers is Larry Clark, one of the luminaries of the LA Rebellion, a constellation of Black auteurs who studied at the UCLA Film School between the late 1960s and the late ’80s.

A group discussing life in Watts in Wattstax. Image courtesy Wattstax.

According to Robert Gordon’s book Respect Yourself: Stax Records and the Soul Explosion (2013), Stuart wasn’t pleased after seeing a first edit of the film, describing it as “a big newsreel of a concert.” Taking to heart Shaw’s notion of the film as a mirror, he suggested incorporating on-the-street interviews—an idea ultimately replaced with using unknown actors (of varying ages, though most seem to be thirty-five or younger) to freely riff on a range of topics: the legacy of the Watts uprising, racism, the opposite sex, hair, religion, pride. “Black is beautiful because it feels so good,” one woman in a beauty salon proclaims, her brio typifying these unscripted musings and observations. (One of those performers is Ted Lange, seen here five years before The Love Boat made him a TV star.)

Rufus Thomas onstage in Wattstax. Image courtesy Wattstax.

Even with these segments added, Stuart still felt the film wasn’t complete; as Gordon recounts, the director told the team behind the documentary, “We need somebody like the chorus in Henry V, and we need a comic person to do this, to express the feelings of the people in one person.” He was advised to catch a show by Pryor, then not nationally known and just a few years removed from his square, Cosbyesque middlebrow standup routines of the ’60s, a style he had abandoned for corrosive, coruscating social-observation comedy. Pryor’s vignettes in Wattstax—on Black nationalism, cops, getting a job—evince the genius memorably summarized by Hilton Als: “Instead of adapting to the white perspective, he forced white audiences to follow him into his own experience. Pryor didn’t manipulate his audiences’ white guilt or their black moral outrage. If he played the race card, it was only to show how funny he looked when he tried to shuffle the deck.”

Jesse Jackson (center) and Al Bell (right) in Wattstax. Image courtesy Wattstax.

The polyphony of Wattstax is soaring and expansive. Every element is apposite, whether it’s the crowd going wild as fifty-five-year-old Rufus Thomas sings “Do the Funky Chicken,” Pryor reminiscing about taking part in police lineups as a teen “for something to do,” or a woman discussing “the search for awareness.” Maybe the greatest sonic triumph, though, is the sound of more than one hundred thousand spectators repeating in unison MC Jesse Jackson’s signature declaration: “I am somebody.”

Melissa Anderson is the film editor of 4Columns.