Brian Dillon

Brian Dillon

Notes on notes: a collection of writings by Moyra Davey.

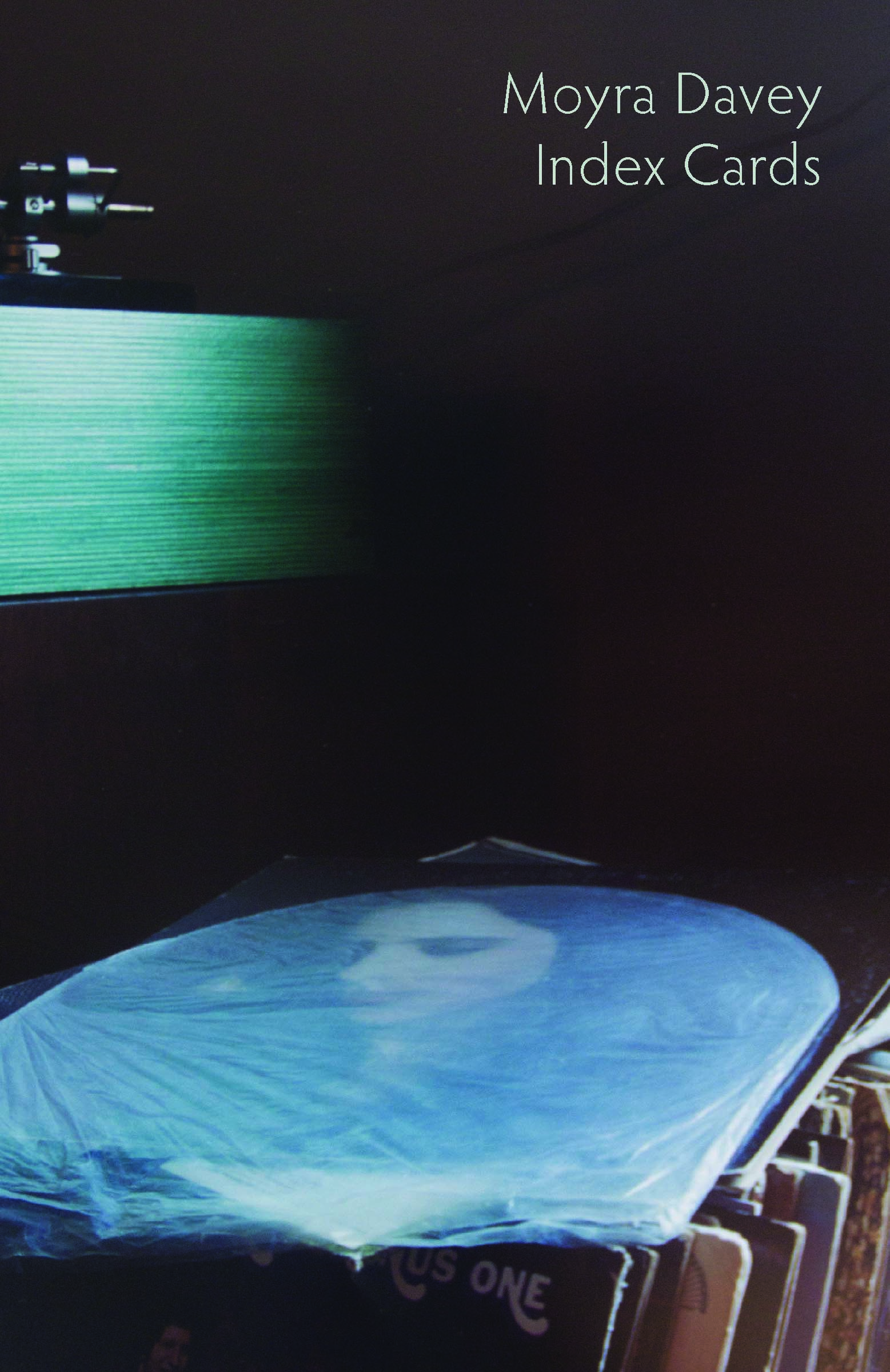

Index Cards, by Moyra Davey, New Directions, 217 pages, $17.95

• • •

“I have always been a maker more than a thinker,” writes the artist Moyra Davey in Index Cards, a collection of essays composed variously for voice, page, and screen. There is some false modesty in this statement of hers: among other things, the book contains Davey’s erudite, subtle, daring thoughts about film and photography, text and image, art and life. Thinker, however, is a word that can land a little lifelessly on ear and eye, suggesting an interest in theory over texture. Davey’s self-description holds: from her earlier photographs—her sisters grouped like Graces, studies of dust in the artist’s studio, candid pictures of people writing on the New York subway—to her current practice of self-narrated essay films, she has been more concerned with connections than concepts. In Index Cards, Davey invents, and self-consciously frets about, a type of writing in which voice and mood are everything.

I’m following Davey’s publisher in calling these fifteen pieces essays, but that is rather begging the question. A famously ill-defined genre, the essay overlaps with many other forms, such as lectures, diaries, notebooks, letters, and aspects or modes of fiction and poetry. Superficially, you could describe some of the texts in Index Cards in terms of their subject matter. Here is Davey on her time in analysis, on living in post-9/11 New York, on her anxious and vagrant reading habits, on the fraught lives of her sisters, on being diagnosed with multiple sclerosis in 2007, and on the effect of the illness on her body and her body of work. Except—none of the essays ever seems quite so stable and certain of its theme: “I’m piecing together fragments because I don’t yet have a subject.” And, more disorienting for us, her readers, there are occasional vestiges or reminders of an essay’s origin as onscreen voiceover: “[Short interlude in which narrator is seen blowing dust from her books].”

Those books are ever present in Index Cards, as they have been in Davey’s recent films. In the first piece, “Fifty Minutes,” she says she thinks about her library the way she thinks about her more-or-less well-stocked fridge: “I have to manage these as well, prioritize, determine which book is likely to give me the thing I need most at a given moment.” Certain authors and their works keep returning, not as authorities to be respected but fetishes to be handled, lessons incanted time and again. That some of these writers are critics or scholars—Walter Benjamin, Roland Barthes, Susan Sontag—should not suggest an academic approach on Davey’s part. Instead, following also the likes of Virginia Woolf, Robert Walser, and Jane Bowles, she experiences reading as drift and reverie. She wants to know where (inside herself, and outside) her talismanic texts will take her.

In Davey’s films, she’s often seen in her studio, speaking aloud a meditation or a narrative that she’s hearing from an earlier recording, now dictated to her on headphones. The artist, or writer, becomes a source and medium of transcription. She hears voices and she takes notes: “Even more captivating than my laments from the journals are other writers’ words, loosely transcribed.” The notebook or diary is for Davey neither purely self-expressive nor an intellectual chore; it’s a place where affinities are established: “Sit at glass-topped table. Copy passages from Benjamin, Barthes. Begin to see new connections.” Benjamin and Barthes were of course also great notetakers, and wrote about their processes—it is hard to read Index Cards without taking notes on your notes, following Davey’s lead.

Davey’s writerly reference points repeat themselves across the essays. Mary Wollstonecraft is a recurring figure—also her radical husband William Godwin, who wrote: “A disappointed woman should try to construct happiness out of a set of materials within her reach.” Davey’s essay “Les Goddesses,” which is the text of a film with the same title, links Wollstonecraft and her daughters (one of whom was Mary Shelley) to the artist’s own family history of ambition, rebellion, desire, and grief. Davey’s father was killed in an accident in 1975, when she was seventeen. She has sisters whose adult lives have been deformed by substance abuse. Such facts appear fleetingly in Index Cards, like an alarming correspondence that’s been tucked away among the pages of her more bookish reflections.

Davey refers to such autobiographical substance as “the Wet”—she is not sure that she really wants to write about the slippery material of private life. (One of the subtexts of her book is Davey’s protracted overcoming of the Conceptual ban on affect and autobiography that was so much in force when she was a young artist.) But she is herself a constant presence in these pages: “Half out of my mind with drugs and frozen fingers.” Her illness means intermittent blindness, chronic constipation, getting out of bed some days and promptly falling over. She identifies with sick writers such as Christopher Hitchens and Dennis Potter, eking out their word counts to the last, in a kind of valedictory joy. The abiding sense one gets of Davey in Index Cards is of a body laboring, following Godwin’s advice and turning everything at hand—books, images, objects, her own symptoms—into work.

In a short, diaristic piece titled “Transit of Venus,” Davey quotes Leonard Cohen: “mood is all.” Davey’s work so bristles with citations and explorations of the work of others that describing it can easily slide into mere list making. But actually, mood is all, and in spite of its digressive qualities, this book maintains a distinctive, inquiring voice. The artist may suffer, as she tells us, “insane mood swings,” but Index Cards feels all of a piece. Davey’s tone throughout is at once curious and recursive, sure enough of her wandering method and sufficiently unsure of where it is leading her. The main impression one comes away with is of an eminently generous mind and maker.

Brian Dillon’s Suppose a Sentence will be published in September by New York Review Books.