Erika Balsom

Erika Balsom

In Richard Brooks’s 1977 film starring Diane Keaton, a lurid portrait of clashing value systems in a moment of societal transformation.

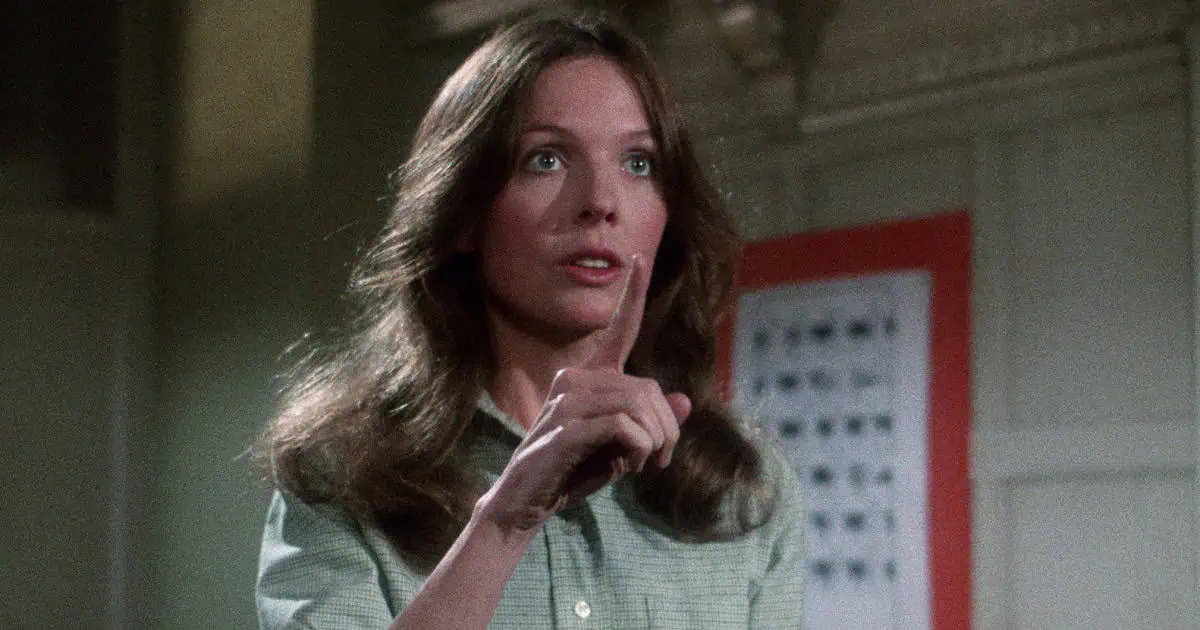

Diane Keaton as Theresa Dunn in Looking for Mr. Goodbar. Courtesy Film at Lincoln Center.

Looking for Mr. Goodbar, directed by Richard Brooks, screening February 13 and 17, 2026, Film at Lincoln Center, New York City

• • •

Deep into Richard Brooks’s grim and sexy Looking for Mr. Goodbar (1977), a new picture suddenly appears on the wall of the apartment occupied by Theresa Dunn (Diane Keaton), a teacher of deaf children who has recently decamped from her oppressive Catholic family and begun exploring her sexuality by picking up men in bars. It is a charcoal portrait of a woman rendered in a stark, Expressionist style, with the neck elongated and mouth splayed open in what looks like a scream. The figure stares out in inflamed horror, hair rushing forward as if blown by a gale. “Jesus, who’s that?” asks an old married guy Theresa has brought home. “Me, when I need a fix,” she quips, by this point fully rid of the guilelessness she possessed at the film’s start. No further mention of this medusan image is ever made, but it appears repeatedly as Goodbar hurtles toward its hallucinatory climax, in which Theresa is stabbed to death by a man who can’t get it up. Forget about a denouement; the film ends there, brutally, with a strobe light flickering as her face recedes into a black void. Is this story of doomed promiscuity a warning to carnally curious women everywhere?

Diane Keaton as Theresa Dunn in Looking for Mr. Goodbar. Courtesy Film at Lincoln Center.

The druggy penumbra that Theresa inhabits by night is a far cry from the Technicolor domesticity of a melodrama like Douglas Sirk’s All that Heaven Allows (1955). Yet this superficial difference belies two important commonalities: both films focus intensely on the unsolvable problem of female desire within patriarchal society, and both make expressive use of mise-en-scène. Screaming before Theresa does, the charcoal drawing externalizes her debasement and seems to proclaim the inevitability of her fate. It frames Goodbar as a punishment narrative, a lesson in what happens to good girls who go bad. Early on, when Theresa sees images of a women’s liberation march from 1970 on television, the male announcer declares, “This was to be the decade of the dames.” “Was to be”? The phrasing leaves open the possibility that history had other plans: reaction, backlash. In her 1978 New York Times article “Hollywood Rediscovers the American Woman,” Joan Mellen gives Goodbar a prominent place alongside titles like An Unmarried Woman (1978) as evidence of cinema’s response to the feminist upheavals of the 1970s, yet argues that it is one of “a number of current, woman‐centered films [that] cope with the rebellion of women against traditional roles only to support the status quo by discovering that the new styles of life are painful and destructive, thus reinforcing the conventional by negative example.” The same could be said of Goodbar’s depiction of gay men, who cavort with Theresa at a disco she frequents: it seems like a fun aside at first, but ultimately turns sour to fulfill a decisive narrative function. Brooks’s film weighs the promises of emancipation against the persistence of heterosexual norms and delivers a crushing verdict.

Richard Gere as Tony and Diane Keaton as Theresa Dunn in Looking for Mr. Goodbar. Courtesy Film at Lincoln Center. © Paramount Pictures Corporation.

As in Sirk, however, it’s not so simple. For one, there is the important matter of Diane Keaton, the exquisite actress who died this past October at the age of seventy-nine and is now the subject of a weeklong tribute at Film at Lincoln Center. Theresa is reading Mario Puzo’s The Godfather (1969) at a bar when she meets Tony, a febrile brute played by a young and pretty Richard Gere, with whom she soon strikes up a volatile liaison. “I’ve seen the movie,” he says in an extratextual nod to Keaton’s turn as Kay Adams-Corleone in Francis Ford Coppola’s 1972 and 1974 adaptations, in which she is a patient, naive accessory. With Goodbar, Keaton trades the conformist ignorance of that supporting role for the expansiveness and self-knowledge of the main player, with the result that the performer blossoms in a manner that echoes the trajectory of her character.

Diane Keaton as Theresa Dunn in Looking for Mr. Goodbar. Courtesy Film at Lincoln Center.

Notably, Goodbar—which was adapted from a best-selling 1975 novel, in turn inspired by a real 1973 murder—appeared the same year as Woody Allen’s Annie Hall, a film partially based on the director’s relationship with Keaton, and for which she won an Academy Award for best actress. Elements of her performance style are shared across the two roles, but it is in Goodbar that she shows a greater range, released as she is from Allen’s narcissism, set loose across a diverse array of situations. Both films are enamored with the zeitgeist, but the Marshall McLuhan cameo, cocaine sneeze, and “la-di-da” ease of Annie Hall sit at a considerable distance from Theresa’s solo forays into the dark. Allen’s Alvy Singer is overcome with sexual anxiety, yet Annie is lucky to live in a world in which the violence that pervades Goodbar does not exist, where neurosis is played for laughs, and death comes only to lobsters and spiders.

In Theresa’s case, even the ostensible nice guy, welfare worker James (William Atherton), is threatening. He stalks her, Tony beats her, her father rages at her, her married professor/lover confesses that he “just can’t stand a woman’s company right after [he has] fucked her,” and she ends up dead. Misogynist violence is ubiquitous, and the freer a woman is, the more likely she is to provoke it. By representing this in such lurid detail, with Keaton’s beguiling naturalism and eccentric vulnerability attracting the viewer’s admiration and identification like a magnet, Goodbar becomes something other than a mere tale of chastisement: it offers an account of clashing value systems in a moment of societal transformation.

Diane Keaton as Theresa Dunn in Looking for Mr. Goodbar. Courtesy Film at Lincoln Center.

Mellen argues that Goodbar “views the Diane Keaton character as a clinical object, data for a class study of the perils visited upon the woman who is denied the ‘normal’ joys of life: childbearing and a home.” While the film does offer Theresa’s congenital scoliosis as motivation for her refusal of maternity, there is no other indication that she has been “denied” anything. And it is difficult to sustain that she is seen as an object, given how persistently the film visualizes her fantasies, in a manner that recalls the disruptive dreamlife of Germaine Dulac’s The Smiling Madame Beudet (1923). It is thrilling to watch Theresa move through discos and bathrooms and taxis and bedrooms, improvising and taking risks. Something surfaces though all this that her gruesome end cannot contain. She dares to be both night and day, to baffle the binary. As she gets deeper into sex, her apartment decor comes to include not just the charcoal drawing but also a glamour portrait of her “bad” sister, Katherine (Tuesday Weld)—a swinging, drug-taking, abortion-getting airline hostess—and a glass chandelier depicting myriad sexual positions handed down from Katherine that Theresa hangs above her bed. These emblems of sororal complicity and erotic liberation occupy the same space as the sketch of the scream; together with it, they form a knot that cannot be untied, only cut.

In her classic essay on Sirk, published the same year Goodbar was released, Laura Mulvey proposes that “the strength of the melodramatic form lies in the amount of dust the story raises along the road, the cloud of overdetermined irreconcilables which put up a resistance to being neatly settled, in the last five minutes, into a happy end.” In Goodbar, the concluding plunge is into tragedy, but the idea still holds: so much “dust” gets kicked up in this film of feminine imagination and masculine terror that, even if Theresa gets killed in the end, there is much left lingering in the air—in no small part because of the ingenuity Keaton brings to the role. In cinema, the dramatization of contradiction is reliably more interesting than a depiction conforming to beliefs already held.

Erika Balsom is a Reader in Film Studies at King’s College London. A collection of her criticism, The Edges of Cinema: Essays on Twenty-First Century Film Culture, will be published by Columbia University Press later this year.