Sasha Frere-Jones

Sasha Frere-Jones

A new reissue of Greg Tate’s 1992 essay collection hits hard with the truth, again and again.

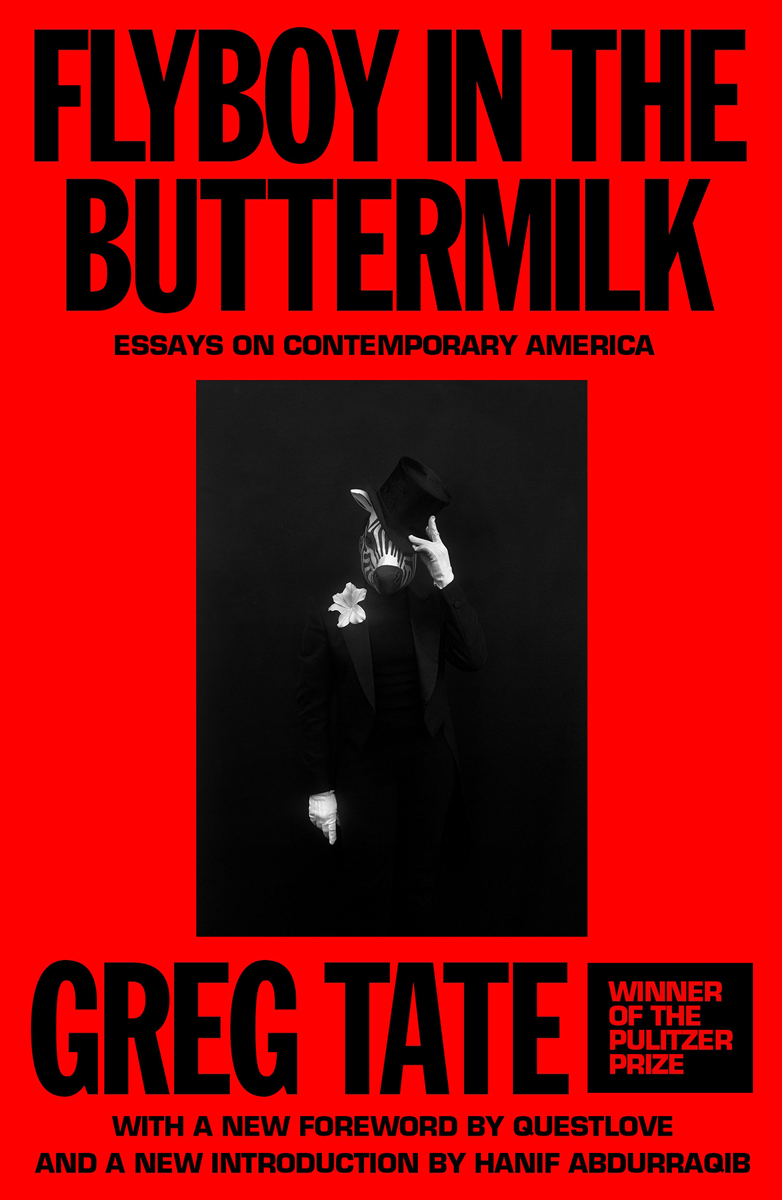

Flyboy in the Buttermilk: Essays on Contemporary America, by Greg Tate, AUWA Books, 336 pages, $18

• • •

Gregory “Ironman” Tate wrote as if Black Music were a person, sitting beside you, and that white supremacy was as immediate as fresh shit in the president’s pants. Of course we have to talk—can’t you smell it? Black Music, for Tate, was a compound noun, two words conjoined like family names, a material and spiritual dependence that entertainment could not dissolve. The context, in 1982, for the first thing I ever read of Tate’s, was the ressentiment of punks who had taken their final shot and decided to call it hardcore, Americans grasping to repatriate the Ramones after the British revision. Tate put them on a poster: “Hardcore? I can’t use it. Not even if we talking Sex Pistols. ’Cause inner city blues make me wanna holler open up the window it’s too funky in here. And shit like that. Or rhythms to that effect.” These are the opening sentences of “Hardcore of Darkness,” his 1982 Village Voice column about Bad Brains, the first Black hardcore band in a scene that never admitted a second one. Were writers like this Ironman guy common? No. The forty pieces in the newly reissued Flyboy in the Buttermilk—first written between 1981 and 1991, almost entirely for the Village Voice, and published as this collection in 1992—are still an island. Tate’s original text is unchanged, but other things are not. Since his death in 2021, Tate has gotten a posthumous Pulitzer and Flyboy has gained new introductory texts by Hanif Abdurraqib and Questlove, whose imprint, AUWA, is publishing this new version this spring.

Tate hit as hard as the music he wrote about, and his columns were often more important than his topics. Now obscured, that “Ironman” middle name was both announcement and alignment pact, an echo of noms de funk like Robert “P-Nut” Johnson or Gary “Mudbone” Cooper. I didn’t know that writers could talk like Tate, that rap and hardcore had champions this strong, that I would have to come up with a politics real quick to accompany my listening, that there would be no doctor’s notes accepted at this academy. Nobody was going to give away the reality of Bad Brains and George Clinton for free, not after the music had been stolen. This was America, and the first person to make that clear to me was Greg Tate. It was a relief, in fact, to have a Black writer pulling the music back from its buttermilk context. Tracing the genocidal moves of America, it is disorienting to pretend that Black artists are always happy to speak to white audiences, even the ones with white money. Tate dispersed the visceral dissonance with the truth, again and again, making it clear that whites were not his intended readers.

From that same review: “Now when spike-headed hordes of mild-mannered caucasoids came back from the Brains’ first gigs raving that these brothers were ferocious, I took the brouhaha for okey-doke.” His affect was his own and his list of tasks, too. Describe the songs on the album? Give us background information? Make anything easier for the colonizer? Do fries go with that shake? Tate, in the Bad Brains essay, also makes ad hoc fun of Bush Tetras, Gang of Four, and the Clash, whom he calls “Butch Tarantulas, Hang All Four, and the Cash.” Not even saying that was warranted, but it set the mood.

The Village Voice allowed writers room to revise the form as much as the content. Tate’s 1989 review of Ice-T’s Power is a posse cut that is almost all guest verses in the forms of extensive quotes from the Associated Press, New York Times, Ice-T, Mike Davis (twice), Eric Foner, Toni Morrison, and Roland Barthes. And “Black Music” was a cohort not limited to music: music, in fact, was not limited to music. In his 1986 essay “Cult-Nats Meet Freaky-Deke,” Tate went in search of a Black post-structuralism that involved remixing Baudrillard and Marx, and also citing the Basquiat mural in the Michael Todd room at the Palladium, which is something you’d likely have seen in person before the internet provided a gallery of every object you were ever thinking about. And even if he is paraphrasing Hal Foster, Tate’s remix is the one I play: “Resistance, then, doesn’t aim for transcendence of corporate culture’s limits into some mythical liberated zone, but for critical intervention in the process by which capitalism is rationalized through mass culture and modernism.” I don’t think Tate would be crossing a picket line to write for Artforum.

The page-long list of influences in the same essay made clear that the coalition of the willing might be wider than expected, and it’s printed without abridgment on my lobes: “Robert Farris Thompson and Professor Longhair, Julia Kristeva and Chaka Khan, Kurt Schwitters and Coptic scrolls, Run-D.M.C. and Paolo Soleri, Fredric Jameson and Reverend James Cleveland,” and so on. One did not, in fact, need to be desperately seeking Don DeLillo or Ornette Coleman or Cecil Taylor or Lisa Kennedy to see Tate’s deeper class project, the passionate defense of reading and writing as fundamentally disruptive, fertile adventures that were not primarily intended to soothe or reassure. The war in Tate’s pieces was not going to be resolved by the funk in his language, and the stakes have only deepened as the blood flows more freely. As he wrote, “The idea that the human brain first began functioning in Europe now appears about as bright as Frankenstein’s monster.” Basquiat is the flyboy in the titular 1989 essay, though Tate may have known deep down he was cited as reverently as the painter. “Given the past and present state of race relations in the U.S.,” Tates writes, “the idea that any Black person would choose exile into ‘the white world’ over the company and strength in numbers of the Black community not only seems insane to some of us, but hints at spiritual compromise as well.” Tate’s writing made sure that Jay-Z would never be able to collect him. One prays there will never be a Tate biopic.

There are plenty of dad jokes and corny puns in Flyboy, as well as intellectual dead ends and some unnecessarily cruel jokes. (The legacy of ’80s rock crit.) But the beauty of Tate, especially this bag of uncut gems, is that he was not a theorist of a unified field or a strict logician—or even an underdog (his band, Burnt Sugar, made killer records after Tate stopped filing regularly). Maybe the most distinct pleasure available here is the palpable truth that Tate was not auditioning for another job. He wasn’t hoovered into the Liner Notes Industrial Complex or the Affable Talking Head Pipeline, nor did he parlay all of this work into an A&R gig or playlist concierge. Tate didn’t engage with culture with that sort of rueful magazine approach, the clucks-over-the-sad-brutality-of-America-but-hey-what-an-album pellet so much writing is cubed into. Tate knew the brutality is there every time the one comes back around. He just wanted everyone to get up.

Sasha Frere-Jones is a musician and writer from New York. His memoir, Earlier, was published by Semiotext(e) in 2023.