Eric Banks

Eric Banks

In an International Booker finalist, murder and shades of Bolaño.

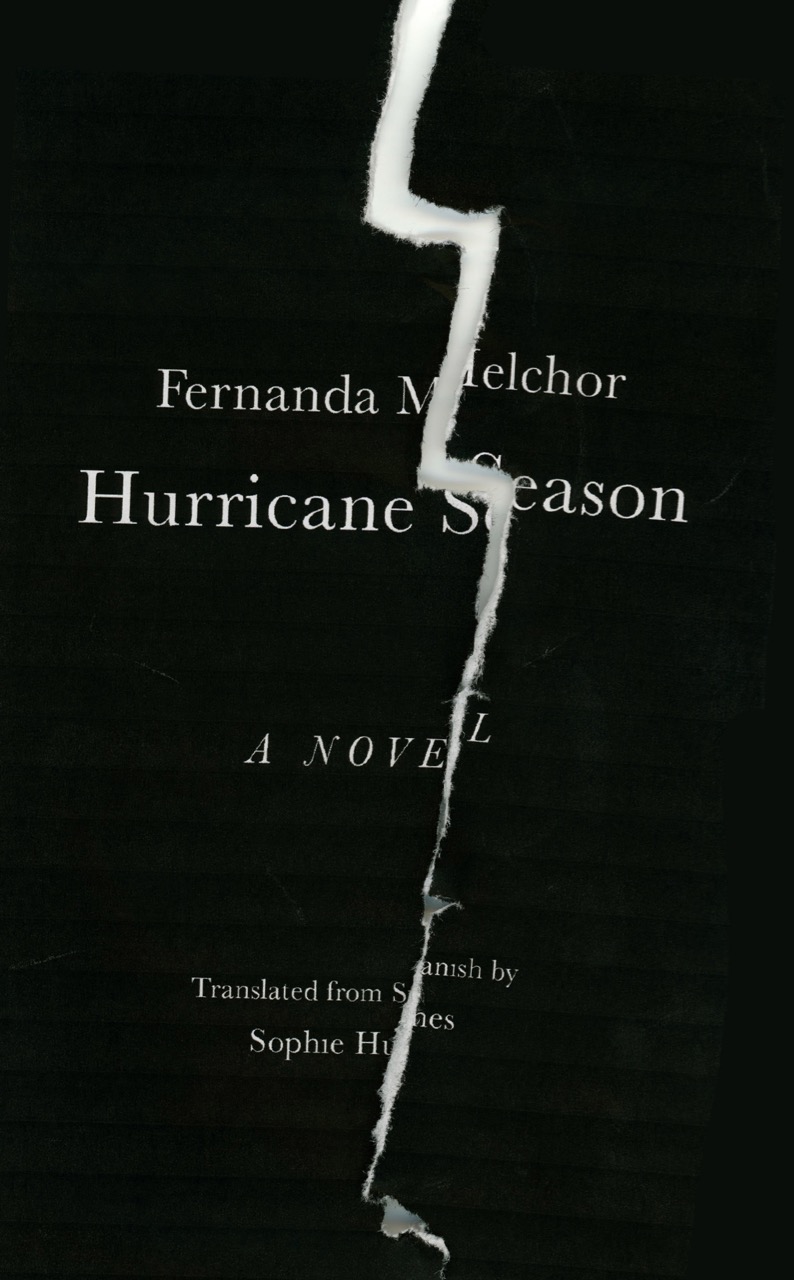

Hurricane Season, by Fernanda Melchor, translated by Sophie Hughes, New Directions, 210 pages, $22.95

• • •

The four-sentence-long chapter that opens Hurricane Season ends with a murder, or more precisely after a murder, with the discovery of a corpse floating in an irrigation ditch, the “rotten face” of which is “recognized . . . peeping out from the yellow foam on the water’s surface.” It’s a cinematic image, Hopper-esque (Dennis, not Edward), River’s Edge crossed with Blue Velvet. Is there any doubt the body will belong to a female figure? The first to chance upon the corpse is a pack of five boys, the odor assaulting them like “a fistful of sand in the face.” Over the course of a single paragraph, Fernanda Melchor’s gangly, drawn out, go-for-broke sentences spider their way forward, from the kids to the discovery to the corpse itself.

By contrast, in true-crime fashion, the Mexican writer’s compact novel cycles backward in time, from the dead body (which belongs to a shrewish, black-clad character named the Witch) to the accretion of facts that establish cause, motive, and execution, narrated in a funky, free indirect style from the point of view of four different accomplices to the larger tragedy of Hurricane Season: the fate of hopeless lives in a society rotted out from violence and hatred. Each chapter is composed of a single uninterrupted paragraph, all of them comprising the author’s teeteringly long, clause-atop-clause sentences. The stylistic effect, in Sophie Hughes’s vigorous translation, is remarkable and peculiar. The accursed village La Matosa, the fabled location of a deadly hurricane decades before, is described for example as dotted

with shacks and shanties raised on the bones of those who’d been crushed under the hillside; [now it is] repopulated by outsiders, most of them lured by the promise of work, the construction of the new highway that was to run right through Villa and connect both the port and the capital to the recently discovered oil wells north of town, up in Palogacho, enough work for fondas and food stalls to start cropping up, and in time even cantinas, guesthouses, whorehouses and strip clubs where the truckers, the traveling tradesmen and the day laborers would stop to take a moment from the monotony of that road flanked on either side by cane fields, cane and pastures and reeds filling every inch of land for miles and miles, in every direction, from the very edge of the road to the low slopes of the sierra to the west, or running eastward to the coast, to its eternally raging waters; brush and brush and more squat brush covered in vines that grew with rapacious speed during the rainy season and threatened to overwhelm homes and crops alike . . .

Let’s end here, though the sentence expands for nearly another page, finally settling on a description of the tawny laborers’ skin (“shiny and dark like the seeds of a tamarind, or creamy like dulce de leche or the tender pulp of a ripe sapodilla”).

La Matosa is a place divided, stuck in time between an awful past and a pitiless present, a mirror of the spectacular violence, particularly the violence against women, that has infested day-to-day life in Mexico. Originally published in Spanish in 2016 and shortlisted for the International Booker Prize in 2020, Hurricane Season takes an epigraphic cue from Jorge Ibargüengoitia’s 1977 true-crime novel The Dead Girls: “Some of the events described here are real. All of the characters are invented.” This is accurate enough as a description of the novel, based roughly on the story of a murder outside Melchor’s hometown of Veracruz, yet it also positions her book in a Capote-Bolaño lineage where true crime and literary fiction cross-pollinate and animate each other, even if its brevity reminds the reader more of the self-conscious tightness of By Night in Chile than the deadpan sprawl of 2666.

In La Matosa, no bad deed goes unpunished, or unrecorded: there is a loose familial and/or sexual overlap—and an overload of mutual loathing—among the members of the core quartet. These overlaps can be literal: thirteen-year-old Norma is a suicidal runaway impregnated by her stepfather; the goth teen Brando, beaten bloody in a La Matosa jail cell, entertains fantasies about murdering his pathetically devout mother as well as his best friend Luismi, whom he also wants to fuck (a polite way of euphemizing the pages of pornographic detail Melchor piles on as content for his fantasy); Luismi is the pill-head sex partner both of Norma and of the Witch, who it becomes evident is not a female figure after all. More distantly, sordid examples of betrayal, rage, and all-around shitty behavior across relations near and far are viciously spelled out by Luismi’s distant cousin Yesenia, whose mission in life seems to be to destroy “that son-of-a-bitch leech” in the eyes of her grandmother; and by Luismi’s hapless stepfather Munra, who staggers across the landscape in a secondhand van. What might sound in shorthand like melodrama has a fleshed-out gravity on the page, and even if Melchor plays with extremes of language—both authorial and in the filthy testimony of her characters—her portrayal of the narrow universe of La Matosa is abundantly down to earth.

The intimacy of La Matosa is potent. Melchor achieves this marked sense of closeness in large measure through her command of style. The sentences create a swirling undertow so that the reader feels palpably sucked in. At the same time, in her multivoiced, vaguely Faulkner-esque passages, the various words and thoughts of her main characters shift suddenly to those of other characters or change register: Munra’s bumbling account of his role in the murder mutates without warning into a police report on the make and model of his vehicle; Norma’s words are interrupted again and again by the verbal onslaught of Luismi’s mother, Chabela. In a strange way, the eye of the hurricane settles over each character at one point or another, as if he or she is, at least momentarily, at the very center of the story. The tumult at the core of Hurricane Story is shared and dispersed equally across Melchor’s fictive world. It takes, as they say, a village.

Eric Banks is the director of the New York Institute for the Humanities at NYU. He is the former president of the National Book Critics Circle. He was previously editor-in-chief of Bookforum and a senior editor at Artforum.