Bindu Bansinath

Bindu Bansinath

Sixty-seven years after it was written, a newly published novel by

Simone de Beauvoir.

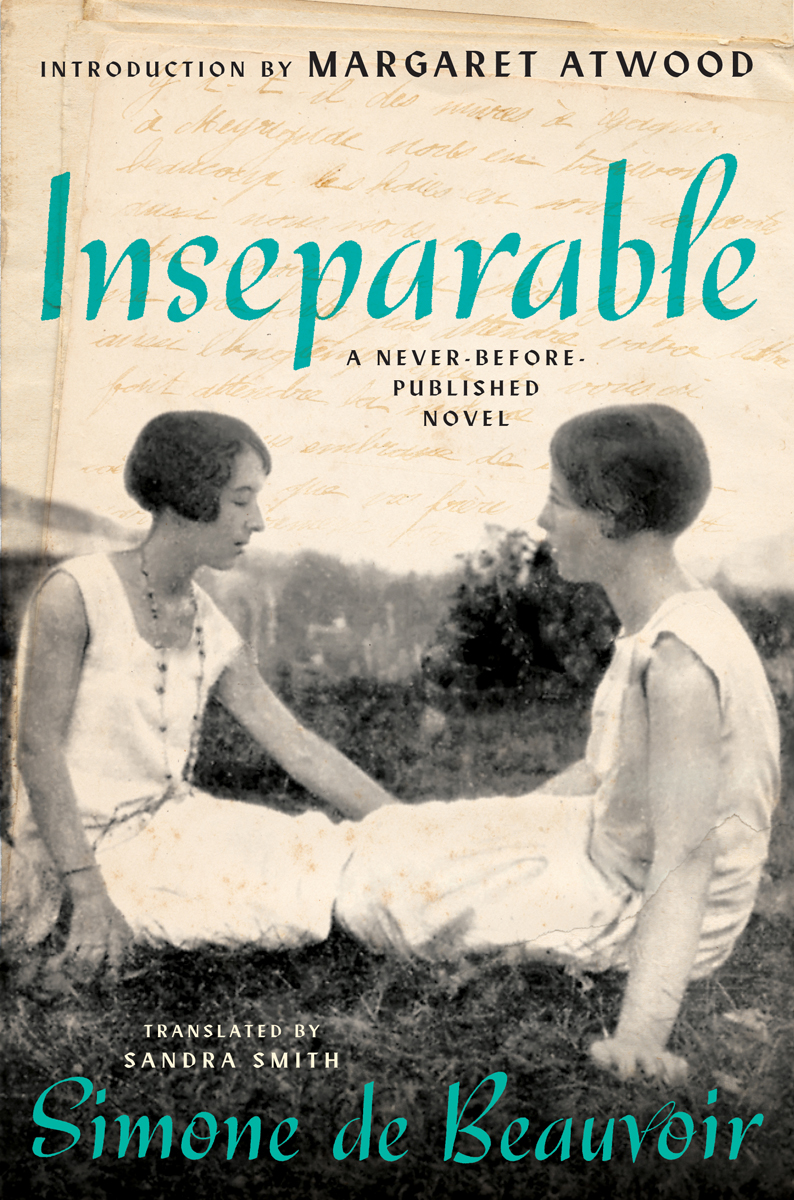

Inseparable, by Simone de Beauvoir, translated by Sandra Smith, Ecco,

157 pages, $23.99

• • •

The buzz surrounding the release of Inseparable, Simone de Beauvoir’s previously unpublished novel, concerns a maddening logistical detail: the book, an intimate story of two female friends in postwar France, was written in 1954 but arrives over sixty years late to shelves. The cause of delay? A man’s discouragement. Beauvoir showed the pages to her partner, Jean-Paul Sartre. Sartre dismissed them as trivial, so Beauvoir filed the work into some drawer of obscurity. Thanks to Beauvoir’s daughter, the novel finds new life now: 157 pages ripped from and then reinserted back into a woman’s oeuvre.

Inseparable was inspired by Beauvoir’s formative friendship with Élisabeth “Zaza” Lacoin, whose death at twenty-one rattled Beauvoir for decades to come. Sylvie, the novel’s shy, observant narrator, is Beauvoir’s avatar, while Andrée—brilliant, confident, with a flair for melodrama—is Zaza incarnate. The ensuing novel is homage and mourning; an exorcism of survivor’s guilt. “If I have tears in my eyes . . . is it because you have died, or rather because I’m the one who is still alive?” Beauvoir writes, in a dedication to Zaza.

The first of the slender novel’s two chapters extols girlhood with rose-colored acuity. When we meet Sylvie, she’s nine, a self-proclaimed “very good girl.” In “The Girl” chapter of The Second Sex, Beauvoir laments how the girl-child becomes passive in womanhood. Girl-Sylvie’s already passive. She’s precocious, however, skeptical of politics and faith—institutions that gaslight women into obedience.

Andrée is the new girl at Sylvie’s day school, and Sylvie is immediately drawn to her. Andrée’s also precocious and smart, but unlike Sylvie, she’s forward and vivacious. As a young child, Andrée burned her thigh cooking potatoes on the campfire. She’s blasé about the pain and how it stunted her: “I was burnt to a crisp and didn’t grow much.” It’s unnerving, Beauvoir’s depiction of a girl learning the life skill of minimizing pain. Sylvie is blind to Andrée’s dismissal of the injury, too busy being fascinated by her: her beautiful handwriting, her misbehavior, her freedom to walk home alone.

Beauvoir’s rendering of girlhood love resonates because it’s imbalanced. Sylvie loves more. While Andrée craves male partnership, Sylvie doesn’t understand the appeal of boys. The only intimacy she imagines is with Andrée, a borderline romance Beauvoir brushes against without explicit acknowledgement: the idea of kissing Andrée while exchanging a hand-knitted scarf; the thought of Andrée’s thigh underneath her school skirt, swollen with burn scars. Sylvie overhears how those wounds reopened during rough play with a boy. Andrée tried so hard to repress her scream that she fainted from pain. “Never had anything as interesting happened to me,” Sylvie thinks, too awestruck to notice her friend would rather harm herself than inconvenience a man.

For Andrée, girlhood isn’t the mythological dreamscape that it is for Sylvie. The freedoms Sylvie perceives aren’t freedoms at all for Andrée. Torn between pleasing God, her mother, and boys, Andrée spends her youth wishing herself older. Many corners of Andrée’s life have tragic edges, but none more so than her naive conflation of womanhood with freedom; a mad-dash hope that the future will be better than the present.

Andrée thinks of herself as unlovable, and Sylvie’s love isn’t enough for her. Andrée wants more than what she thinks female friendship offers; she wants male partnership. Maybe even more, she wants out: high on the swings, Andrée flirts with suicide, an escape from “endless” childhood. Sylvie watches on without understanding; she has too much self-regard to dislike life.

To Andrée, Sylvie is opaque: “We’ve been inseparable for so many years,” Andrée observes, but “I now realize that I don’t know you well at all!” The witness-novel genre hinges on a victim-survivor dynamic. The eloquent survivor observes life; the victim carries out the actual burden of living. But Andrée is more perceptive than the novel’s survivor. A bolder narrative would center her perspective instead of gazing at it from a hyper-analytical afar. Regarding Sylvie, Andrée is astute: readers don’t know Sylvie well, either. Beauvoir relies so heavily on our fascination with Andrée’s trauma that she neglects to give Sylvie a storyline. The book isn’t about two girls anymore. It becomes one girl bearing witness to the other, and not seeing her at all.

What frays inseparable female friendship? The close bonds bred in the isolation of school, in dreaminess and irreverence—those bonds become untenable in adulthood. You are each other’s world, until the world announces you need more than each other: men, homes with copper cookware, to do what God and mothers demand of you. The novel alerts us to the specter looming at the end of girlhood: the woman your circumstances have predestined you to become. She waits to absorb you. You dream of becoming her. Schoolgirl friendship cracks; the external world slips in and waterlogs it. It’s a particular childhood trauma that Inseparable resurfaces into sharp focus.

In Inseparable’s second chapter, Beauvoir fast-tracks to the girls’ college years at the Sorbonne. Womanhood is kind to Sylvie. She grows up inside an implausible vacuum, without family or societal demands—without anything happening at all. Meanwhile, womanhood annihilates Andrée. The confident girl grows into a demure people pleaser, ashamed of articulating her own desires. Both girls attend university, but Andrée knows her future isn’t hers to keep. She understands that her own destiny is “social duties”: parties of clinking glasses; salads preserved in mayo and aspic; women preserved in powder, presented for men to sample.

It maddens Sylvie just how well Andrée camouflages into traditional domestic scenes. The cost of that camouflaging is Andrée’s voice. After a love interest refuses to marry her, she can only express her unhappiness via self-harm. One morning, while picking flowers, Andrée considers cutting herself with shears. “But that wouldn’t have been enough,” she decides, and settles for an ax to the ankle instead. It’s often unclear what Andrée’s desires are, versus what Sylvie thinks they should be. When Andrée finally says what she wants, the act of self-advocacy is so at odds with her people-pleasing socialization that it damages her on a cellular level. She grows feverish and dies; a heavy-handed, albeit prescient, warning against women suppressing self-regard.

After the gravity of Andrée’s death, there’s an extent to which Sylvie’s—and by extension, Beauvoir’s—passivity reads sanctimoniously, as if Andrée is the prototype for “The Girl” chapter of The Second Sex, longing for men, and Sylvie is the inviolable anomaly, content with female friendship. But what’s sanctimonious about a bystander? Witnessing trauma is an accessory to violence, but Beauvoir is too twee with Sylvie to make her confront that violence, or the girl she commits it against.

Inseparable resurrects Zaza in the hopes of giving her justice. Like girlhood love, the literature of mourning is unequal. The writer controls all remembrances, and maybe there’s no justice to be had. Although Sylvie’s wallflower status is frustrating, such stilted remembrance feels deliberate, even sorrowful—it’s Beauvoir who got to fill the pages of a full life. In fiction, she reframes Zaza’s death as an act of subversion, an answer to the morbid question Andrée flirts with on the swings. If you don’t want to become the woman society’s predestined you to be, why not become nobody?

Bindu Bansinath is an assistant editor at Harper’s Magazine. She has written for the Paris Review, the New York Times, the New York Times Magazine, Catapult, New York Magazine, and more. She is at work on her debut novel.