Brian Dillon

Brian Dillon

Dada heads, interior design, and a marionette robot: Tate Modern revisits the Swiss artist.

Nicolai Aluf, Sophie Taeuber with her Dada head, 1920. Gelatin silver print on card, 12.9 × 9.8 inches. Courtesy Stiftung Arp e.V.

Sophie Taeuber-Arp, curated by Natalia Sidlina, Anne Umland, Walburga Krupp, and Eva Reifert, with Sarah Allen and Amy Emmerson Martin, Tate Modern, London, through October 17, 2021

• • •

In the first room of Tate Modern’s airy, meticulous survey of the work of Sophie Taeuber-Arp, the Swiss artist and designer appears in a photographic portrait she commissioned in 1920. Taeuber-Arp is aged thirty-one, her bobbed hair is held back from her face, and she bares a toothy grin. In the foreground is one of her “Dada heads”: a painted orb resembling a darning egg, tapered to a wooden neck or handle. Playful but modest, cheerfully modern—accounts by those who knew her tend to emphasize the blithe qualities in Taeuber-Arp’s work and character. According to her husband, the artist and poet Jean (Hans) Arp, “she was serene, luminous, veracious, precise, clear, incorruptible.” She may herself have had darker ideas, hinted at in a second photograph from 1920, again with the Dada head. Here she has put on a felt hat and black veil, looking altogether more mysterious and slyly attuned to the avant-garde oddity of her doll-like invention.

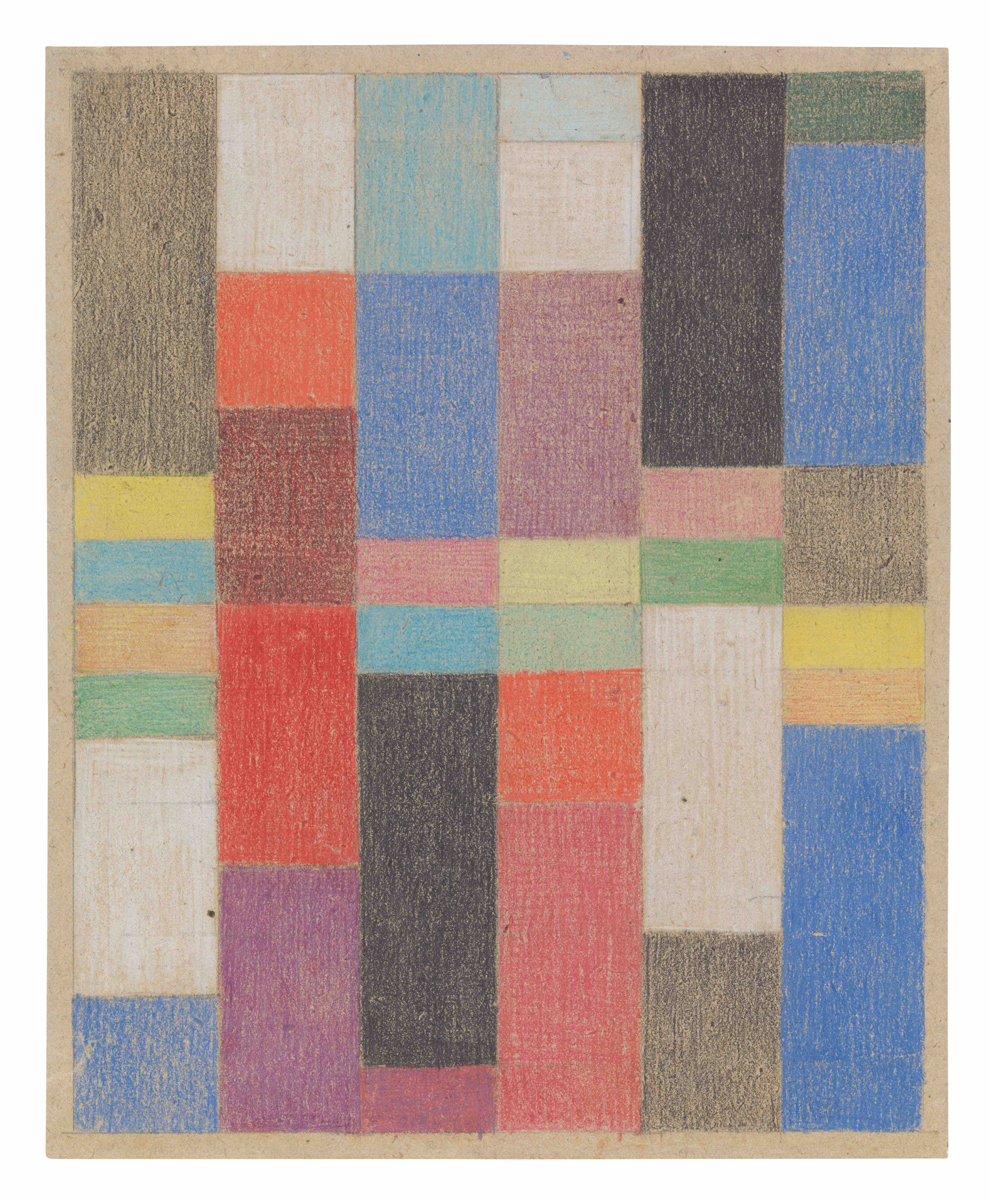

Sophie Taeuber-Arp, Vertical-Horizontal Composition, 1915–16. Crayon and graphite on paper, 23.7 × 19.3 inches. Courtesy Stiftung Arp e.V.

The Tate exhibition does careful justice to the complexities of Taeuber-Arp’s life and work; she is both calm arranger of shape and color (in which capacity she can seem a little too pacific) and an innovator of sometimes monstrous forms and figures—an artist who ranks, in this sense, with contemporaries in Dada and Surrealism. Born in Davos, she attended a French finishing school; studied art in Hamburg and dance in Zurich; made her name initially, around the end of the First World War, with textiles of colorful, geometric aspect. Her beaded necklaces and bags, jewel-hued cushion panels featuring motifs repeated and varied in grids: the patterns of these objects had already been imagined in 1915, in the first of her gouache Vertical-Horizontal Compositions. But Taeuber-Arp—while widely admired in Switzerland, her works frequently exhibited and reproduced—was considered at this time (and for decades after) a craftsperson, not an artist, and so her originality remained hidden from view.

Sophie Taeuber-Arp, installation view. © Tate, Seraphina Neville.

We begin to get a better sense of the other Taeuber-Arp in a photograph of her dancing to a sound poem by the Dadaist poet and impresario Hugo Ball at the Galerie Dada, Zurich, in 1917. She looks as if she were about to topple over, wears a silvery crown atop a grimacing rectangular mask and a dress or tunic adorned with slashing forms. A pair of stiff cylinders enclose her arms, ending in metallic claws; these last recall a costume Ball wore around the same time. Later he wrote about Taeuber-Arp: “There came a dance full of flashes and edges, full of dazzling light and penetrating intensity.” Her Dadaist dance survives only in a handful of such comments and images; but there is something of the same inhuman pantomime in the marionettes Taeuber-Arp made in 1918 for a production of the eighteenth-century commedia dell’arte play King Stag. (The run closed after three performances, due to the arrival of the Spanish flu.) Here is the character of Angela, with her barber-pole limbs and lacy dress; the golden King Deramo, with gilt metal headdress and little bells for hands. And most amazing, the Guards: a bristling silver robot with multiple limbs and heads, closer in its mechanized violence to something fantasized by the Futurists.

Sophie Taeuber-Arp, installation view. © Tate, Seraphina Neville.

Opposite the King Stag puppets at Tate Modern is a vitrine containing a selection of the Dada heads, some of which are more abstract than others, or start to resemble minimalist versions of everyday objects, as in the helmet-like mauve Powder Box (ca. 1918). Taeuber-Arp’s turned-wood productions did not allow her work to escape being dismissed as craft. Even two decades later, when Conjugal Sculpture (made with her husband) was included by Marcel Duchamp in a 1938 group show at the Guggenheim Jeune gallery in London, the work was stalled at customs: it did not qualify as a work of art, according to the director of the Tate Gallery, whose job it was to adjudicate such cases. Peggy Guggenheim appealed, questions were asked in parliament, notable critics protested, and at last the sculpture was released. It’s this sort of incident that no doubt later persuaded Jean Arp, among others of her defenders, to leave his wife’s “applied” art out of the story.

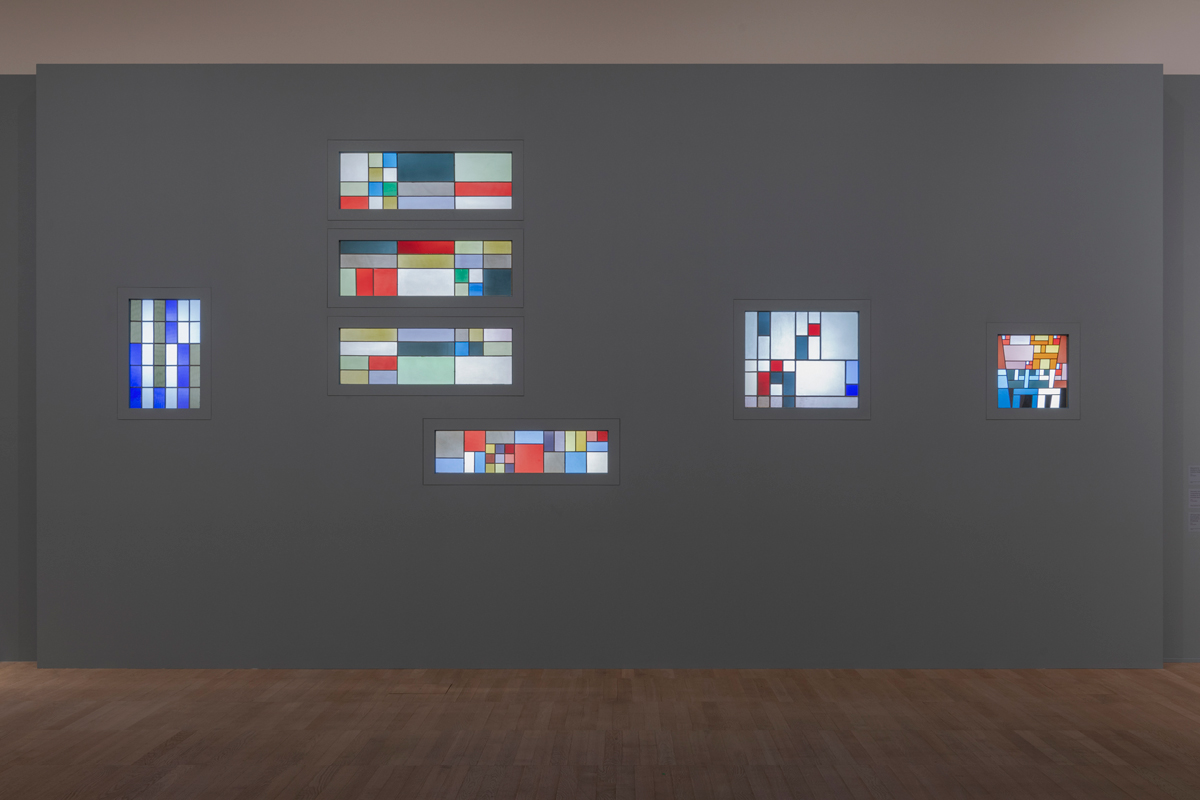

Sophie Taeuber-Arp, installation view. © Tate, Seraphina Neville. Pictured: Sophie Taeuber-Arp’s designs for the Aubette and the apartment of André Horn in Strasbourg.

In the years between her Dadaist pursuits and her running up against Little-England ideas about art, Taeuber-Arp had expanded her practice to include architecture and large-scale interior design. In the late 1920s she worked with her husband and the Dutch artist Theo van Doesburg on the Aubette entertainment complex in Strasbourg. The gridded wall panels and floor-tile patterns she contributed are among the most joyous of her geometric works: the vertical and horizontal experiments of a decade before now remade for the elevation of billiard players and habitués of the Aubette’s foyer bar. In 1929, she moved to France and become entwined in the Cercle et Carré group, which included Gropius, Kandinsky, and Moholy-Nagy. At Clamart, outside Paris, she designed a house and studio in stone and concrete; her rather chunky modular shelving for the house is also at Tate Modern, alongside an equally monumental two-sided desk designed for the apartment of a lawyer, Ernest Rott.

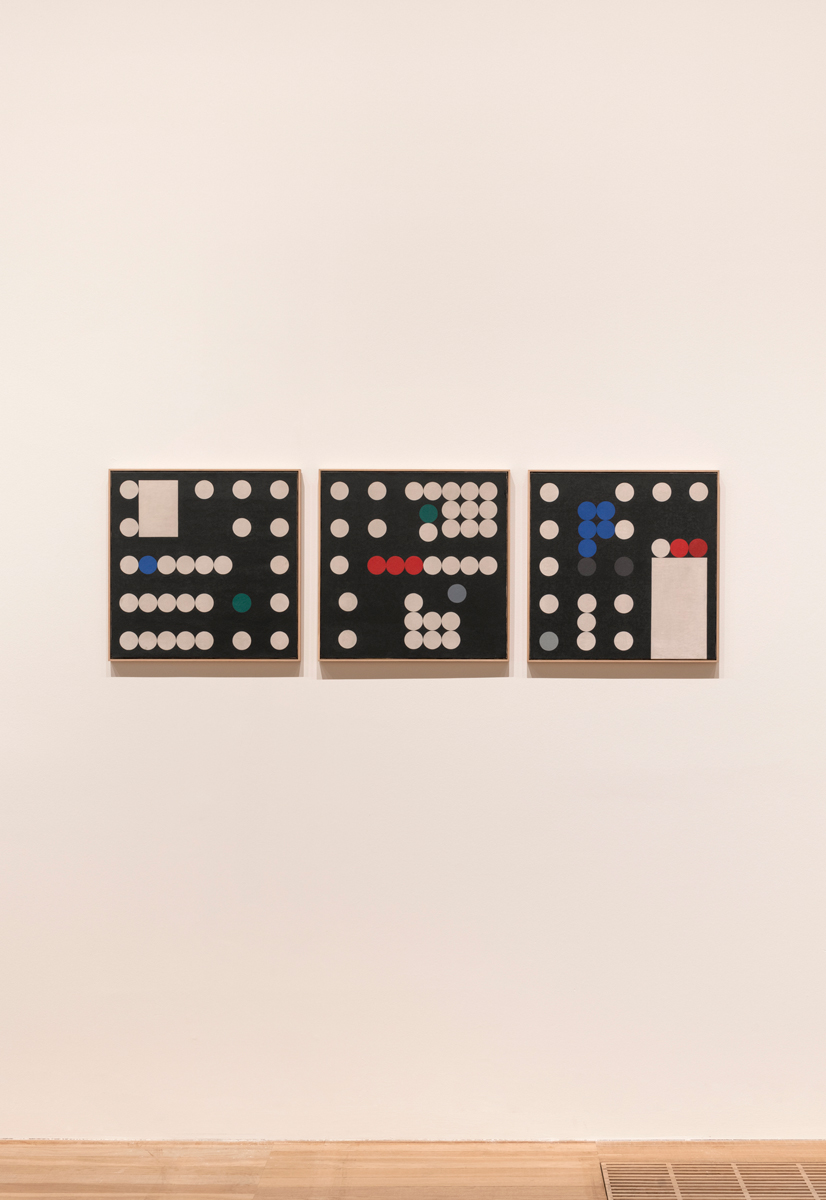

Sophie Taeuber-Arp, Three Circle Pictures (Triptych), 1933 (installation view). Oil paint on canvas, 19.7 × 19.7 inches. Courtesy Hauser & Wirth Collection Services.

Much of the latter half of the exhibition is devoted to Taeuber-Arp’s paintings, and it’s here that the great shifts happen in her work. Renowned for the rectilinear composure of her designs, she now spent almost as much time in thrall to circles and pursuing newly organic forms. The grid doesn’t entirely vanish in works such as Three Circle Pictures (Triptych) (1933), but its main elements are primary-colored discs that wouldn’t be out of place in Pop-derived graphic design forty and more years later. Even more startling are wooden reliefs of the mid-1930s based on or related to these canvases: they look like models for chirpy digital synthesizers made yesterday, with an eye on 1983. Late Taeuber-Arp seems more out of her own time than at any point in her diverse career—speeding into the future. It wasn’t to come. She and Arp fled Paris in 1940, lived in Grasse, and returned to neutral Switzerland late in 1942; Taeuber-Arp accidentally died early the following year, poisoned by a faulty stove.

Brian Dillon’s Suppose a Sentence and Essayism are published by New York Review Books. He is working on Affinities, a book about images.