Liz Brown

Liz Brown

The Hammer surveys twenty-five years of the female body politic in Latin American art.

Silvia Gruner, Arena (Sand), 1986. Super 8 film transferred to DVD, color, silent. 5:50 minutes. Image courtesy the artist.

Radical Women: Latin American Art, 1960–1985, the Hammer Museum, 10899 Wilshire Boulevard, Los Angeles, through December 31, 2017

• • •

I drove to Westwood about a week after the stories first broke. The details kept coming—would keep coming: hotel rooms, bathrobes, bottles of lotion, a potted plant, the banal and bizarre accessories of sexual assault. It was the same with the news-cycle churn and the feasting on outrage and sorrow and other women’s pain, and, as the stories repeated and grew and repeated, a sense of systemic rot set in. November had just begun.

So it was a simple gift to stand in the Hammer Museum and watch Arena (Sand, 1986), a soft, grainy projection in which Mexican artist Silvia Gruner, naked, on a beach, climbs a dune, sits, rubs sand and red pigment over her body, and then somersaults all the way down. The video loops, and Gruner repeats her uphill trek again and again. Sisyphean, certainly, and yet her only burden was herself and that looked like freedom.

The animating idea of Radical Women: Latin American Art, 1960–1985, the museum’s expansive exhibition, is the politicization of the female body as explored in the experimental work of women artists from the Caribbean, Central America, Mexico, South America, and the United States. With nearly three hundred pieces in all manner of media, the show asks: How did female artists use their bodies to make art? How did their art witness and resist the state’s oppression of their bodies? How do their bodies function as sites of liberation? How does the work gathered here assert new histories and new ways of seeing?

That’s a lot of questions, but they do seem valuable at a time when the discovery of a dead woman’s body is a favorite TV trope and Margaret Atwood’s line that “Men are afraid that women will laugh at them. Women are afraid that men will kill them” is in frequent rotation. Among the many inspired aspects of Radical Women is that it doesn’t open with a corpse.

Victoria Santa Cruz, Me gritaron negra (They Shouted Black at Me), 1978. Video documentation of performance, excerpted from the documentary Victoria—Black and Woman, 1978. Director: Torgeir Wethal; producer: Odin Teatret Film. Video, black and white, sound. 3:58 minutes. Image courtesy OTA-Odin Teatret Archives.

It begins, instead, with a shock of pure vitality—Victoria Santa Cruz’s urgent, emancipatory Me gritaron negra (They Shouted Black at Me, 1978), a large-scale black-and-white projection of a performance in which the artist, along with an ardent chorus, recites a poem about a childhood reckoning. With impassioned handclaps and assured dance moves, the Afro-Peruvian choreographer establishes a beat, her own history of refusing of others’ recoil, and the flash transfiguration of shame into pride.

Lenora de Barros, Homenagem a George Segal (Homage to George Segal), 1984. Director: Walter Silveira; sound: Cid Campos. Video performance. 3:07 minutes. Image courtesy the artist and Galeria Millan.

But Radical Women is hardly a blandly anthemic shout-out to female power. It’s too smart, funny, tender, and gross for that. The show, which features over one hundred and twenty women—from well-known artists like Anna Maria Maiolino and Lygia Pape to video pioneers Pola Weiss and Narcisa Hirsch to those who are only now receiving wider recognition—can be seen as a corrective to years of female erasure from canonical art history. Finger-wagging as that may sound, there is little here that comes across as dutiful or ponderous—definitely not the projection of Lenora de Barros’s Homenagem a George Segal (Homage to George Segal, 1984), in which the artist tries to brush her teeth and ends up spackling her entire head with frothy white paste.

Radical Women: Latin American Art, 1960–1985, installation view. “Mapping the Body” theme. Photo: Brian Forrest.

Eschewing chronology, geography, or movement, curators Cecilia Fajardo-Hill and Andrea Giunta have organized the exhibition into thematic groupings—“Body Landscape,” “Performing the Body,” “Mapping the Body,” and so on. The thread of experimentation and discovery runs through all the sections. Ana Mendieta presses a pane of glass to her body, distorting her breasts, her bush, her ass. The question is direct: What happens if I do this with my body? Or this? Or this? And the risk-taking is exhilarating, though, in some works, darker questions also loom: What can the state do to my body? What can the state do to the bodies of those I love?

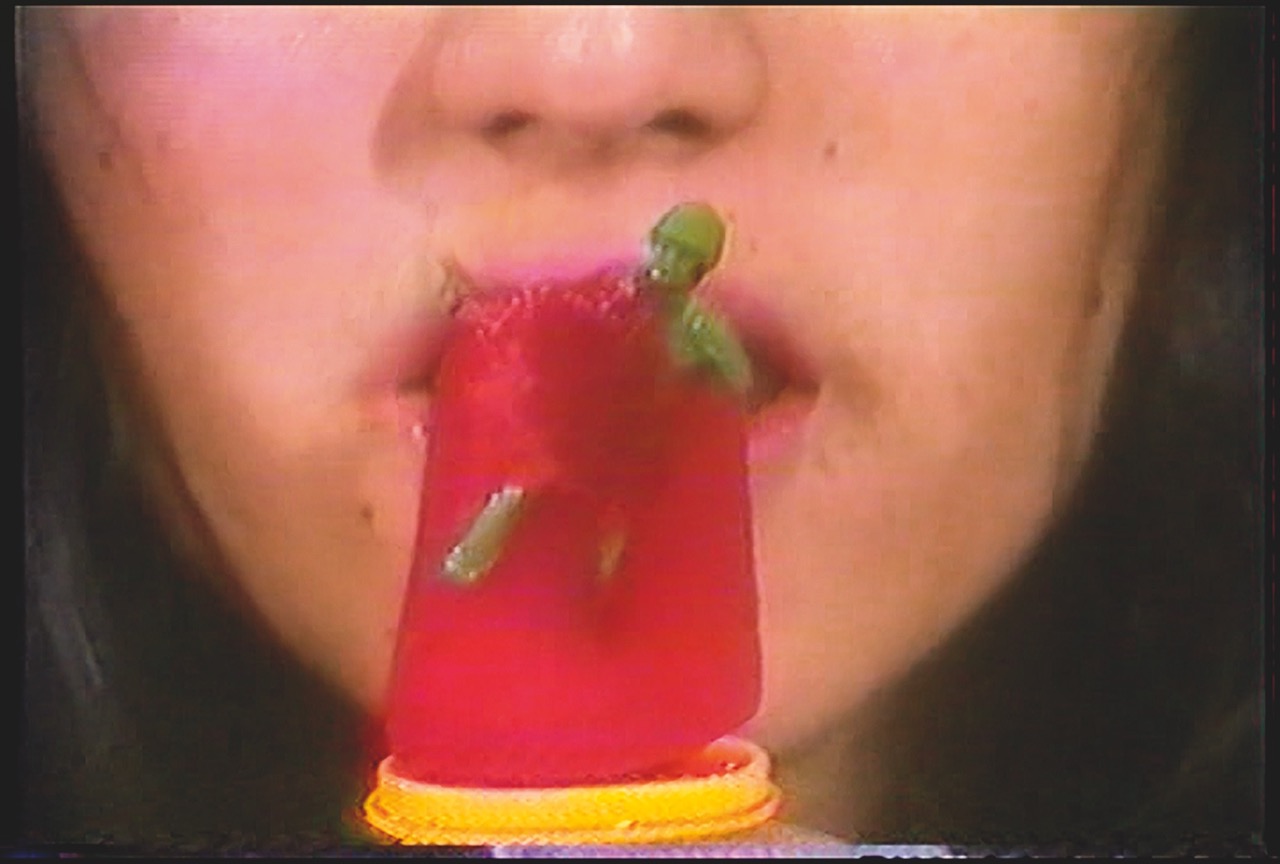

Gloria Camiruaga, Popsicles, 1982–84. Video, color, sound. 6:00 minutes. Image courtesy Museo de Arte Contemporaneo, Facultad de Artes Universidad de Chile.

“DÓNDE ESTÁN?” (Where Are They?) appears below each black-and-white portrait on the paper scrolling down the wall in Chilean Luz Donoso’s Huincha sin fin (Endless Band, 1978), made five years after the CIA-backed coup that ousted Salvador Allende and brought Augusto Pinochet to power. It’s the first piece in the gallery titled “Resistance and Fear.” In a show dominated by video and photography, a massive beige lozenge-shaped cushion beckons. This is Carmela Gross’s Presunto (1968), the word for ham or cold cut. It’s also slang for the dead bodies left in the streets during the over twenty years that Brazil was under military dictatorship. The art in this section evokes the harrowing constancy of living with state-sponsored surveillance, torture, and murder, while sidestepping any lurid voyeuristic buzz. On a monitor, Popsicles (1982–84), a video by Gloria Camiruaga, features close-ups of girls who alternate between robotically licking hard candies with plastic toy soldiers inside and reciting the Hail Mary; the drone of the dead-eyed adolescents with their flushed cheeks and stained tongues is one of the most chilling elements of the exhibition.

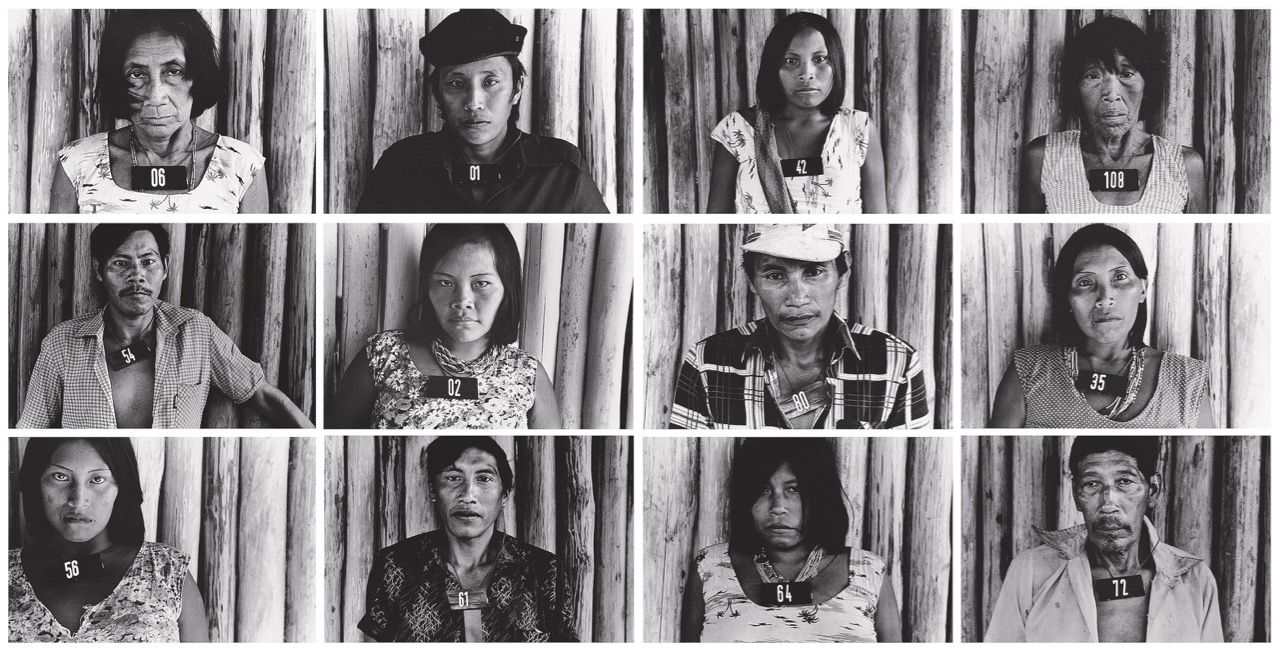

Claudia Andujar, Horizontal 2, from the series Marcados (Marked), 1981–83. Twelve black-and-white photographs. 15 3⁄16 × 22 7⁄16 inches each. Image courtesy Galeria Vermelho.

Later galleries like “Feminisms” and “Social Places” explore women’s rights activism and documentation of disenfranchised groups, including Claudia Andujar’s 1981–83 documentation of members of the indigenous Yanomami community from the Amazon; Isabel Castro’s Women under Fire (1980), about Mexican-American women who were subjected to coerced sterilization in Los Angeles; and Chilean photographer Paz Errázuriz’s La manzana de Adán (Adam’s Apple, 1982–90), depicting residents of a transvestite brothel. Deeply researched, ambitious, and immersive, Radical Women rewards repeat visits, but still, faced with so much to see, read, and absorb, particularly in these narrower spaces filled with grids of images, fatigue arrives.

Lygia Pape, Eat Me, 1975. 16mm/35mm film converted to digital, color, sound. 9:00 minutes. Image courtesy Projeto Lygia Pape and Hauser & Wirth.

The final gallery, “The Erotic,” with fewer and larger works, is a welcome shift in that it demands little and gives a lot, like Zilia Sánchez’s voluptuous labial abstraction, Lunar V (Moon V, circa 1973), and a projection of Lygia Pape’s luscious Eat Me. In the Brazilian artist’s 1975 film, the camera holds on a series of close-ups of men’s mouths sucking on candy and popsicles—coarse, glossy black facial hair; gleaming red lips; a bright wet pink thrusting tongue. The impact on the hypothalamus is immediate—arousal, disgust, arousal. The intellect will catch up later.

It’s puzzling, though, that the erotic has been cordoned off, since so much that came before is also charged with what Audre Lorde called that “replenishing and provocative force.” Still, the curators’ instinct to end with a space that includes the poetic video Memória do corpo (Memory of the Body, 1984), about Lygia Clark’s therapeutic art practice, and Original Sin / Reproduction (1986), a short film in which Silvia Gruner reenacts classic poses from art history, including that of a naked odalisque, who eats the fruit that’s clearly intended as a decorative element (oh hai, Ingres!), feels right. Perhaps it’s more accurate to think of this gallery as one stage of the erotic continuum—the letting go.

In Victoria Santa Cruz’s account of being cast out by her childhood friends for being the only black one among them—the experience that inspired her iconic poem that opens the exhibition—the artist describes not only how powerful her sense of suffering was but also her sense of discovery. “Suffering,” the artist explained, “hides the door. The secret is not to leave, but to go through it.” Radical Women shows us that door.

Liz Brown is currently at work on Twilight Man: The Strange Life and Times of Harrison Post, to be published by Viking. Her writing has appeared in Bookforum, frieze, London Review of Books, Los Angeles Times, New York Times Book Review, and elsewhere.