Bliss Broyard

Bliss Broyard

Fake it to make it: Kevin Young looks back at the history of

American hoaxes.

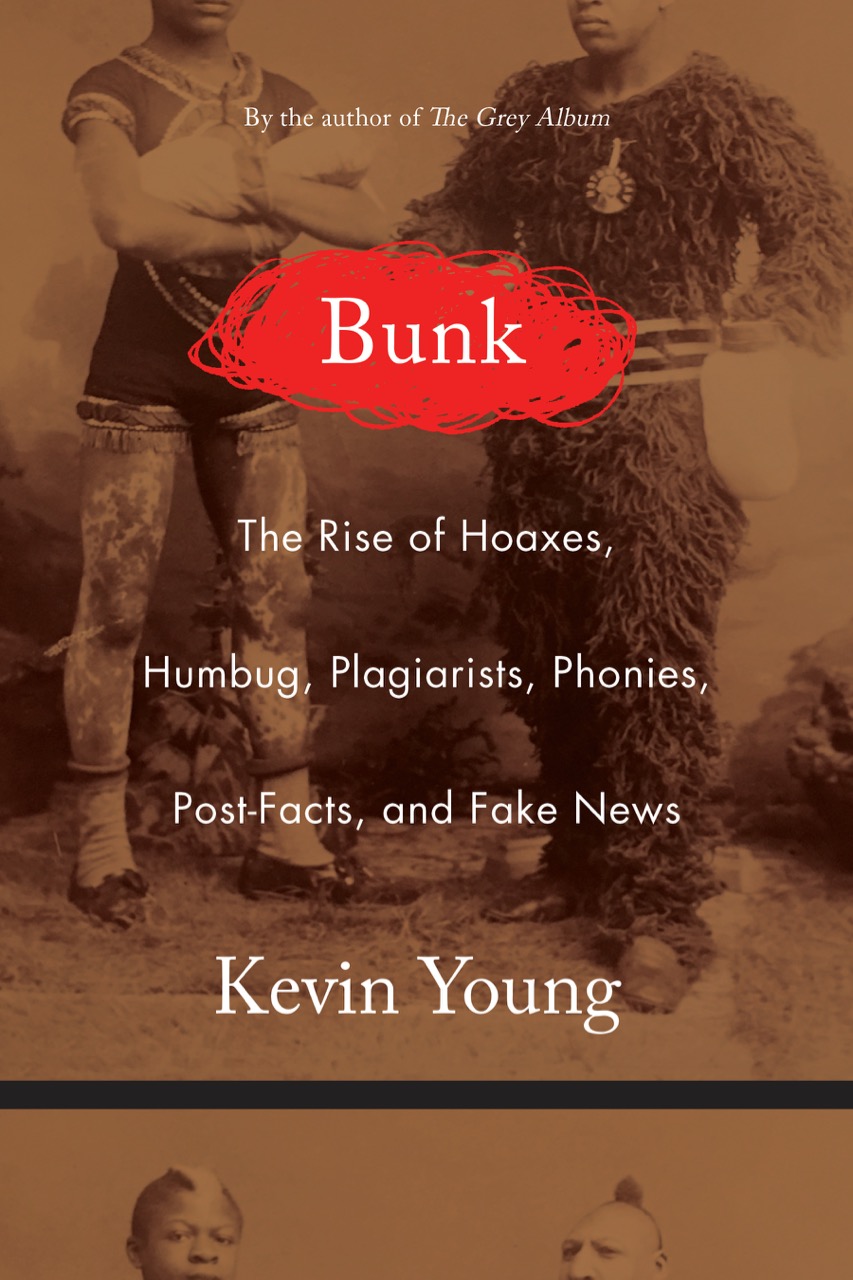

Bunk: The Rise of Hoaxes, Humbug, Plagiarists, Phonies, Post-Facts, and Fake News, by Kevin Young, Graywolf Press, 560 pages, $42

• • •

Ten years ago, I came across a review of my memoir One Drop on the Goodreads website by No. 1 reviewer “Ginnie Jones” that I recognized as identical to one that had appeared in the Washington Post under a different byline. The original review was “mixed-negative,” in the parlance of publishing, but it was Jones’s copying of it that particularly grated. I wrote a comment pointing out the plagiarism and questioned whether Jones had actually read the three thousand books she reviewed to earn her vaunted title. Other Goodreads members jumped to her defense. She was a retired librarian from Pasadena with an ailing husband! How dare I question her integrity! Jones herself chimed in to claim that she’d simply forgotten to include the citation from the WaPo piece, but she had indeed read my book and stood by her three-star judgment.

I was vindicated two years later when Jones was revealed to have plagiarized the majority of her reviews. But I still marveled at the audacity of her hoax and that she’d gotten away with it for so long. I shouldn’t have. In Bunk: The Rise of Hoaxes, Humbug, Plagiarists, Phonies, Post-Facts, and Fake News, Kevin Young makes clear that people like Jones and her enabling supporters are part of a longstanding American tradition.

Drawing a line from P.T. Barnum’s first “humbug” in 1835—in the form of Joice Heth, a black woman he likely bought as a slave and then displayed as the 161-year-old nursemaid to George Washington!—to the fraudulent origins of the spiritualism movement, to the spate of fake memoirists in the early 2000s, to racial impostor Rachel Dolezal, to the alternative facts and #fakenews popularized by Donald Trump, Young demonstrates how time and again Americans are fooled and schooled.

Young, who is also an accomplished poet, describes the process as a kind of call-and-response that coaxes into being “beliefs the hoaxers themselves may not have been aware of.” Often these beliefs involve race and difference: the hoaxed’s sense of superiority and secret fears are affirmed after witnessing the black woman on display as if on the auction block, or hearing tell of Muslim terrorists and/or Mexican rapists. Just as “Barnum’s racial grotesques ultimately met the broader culture where it lived, or at least where it dreamed and hoaxed,” Trump also “exploits deep-seated social divisions, ones that, despairingly, echo the very same ones of race and difference on which the history of the hoax has long relied.”

And yet as Young conveys in his vivid storytelling, there is something undeniably irresistible about a bold con. Take the midlist writer Clifford Irving, who presented himself in 1971 as the authorized biographer for millionaire recluse Howard Hughes to wrangle a $750,000 book deal. When his book Fake! about Hungarian art forger Elmyr de Hory didn’t break out, Irving decided to create a forgery of his own: a handwritten letter from Hughes praising Fake! and suggesting that Irving might be just the guy to write his own story. Hughes was the perfect subject, rich and famous but virtually absent from public life for the previous fifteen years. The gig was up when Irving’s wife, posing as Helga Hughes, was caught on security cameras in Switzerland trying to deposit the advance checks made out to H.R. Hughes. Irving spent seventeen months in prison as a result, but he won the notoriety he craved: Orson Welles’s 1973 film F Is for Fake features the episode, and Irving eventually wrote his own book about it, The Hoax, which became the 2006 movie of the same name starring Richard Gere.

The goal today in our social-media age, Young tells us, “seems to be to narrate your life before others do it for you . . . To opt out as Hughes had is to court monstrosity.” But the public’s appetite has been primed for a reality where truth matters less than “truthiness.” Even after revealing that James Frey’s story of addiction in his memoir A Million Little Pieces was fabricated, Oprah Winfrey defended the book (which she later walked back) because its underlying message of personal redemption resonated with so many. The sniff test becomes “if it feels real, it is,” as Young observes. “The hoax doesn’t represent the vagueness or difficulty of truth but our unending desire for belief.”

By co-opting the voices of the marginalized and delivering them back in cartoonish distortions, “hoaxers erase those their story purports to represent.” Young offers the example of Love and Consequences: A Memoir of Hope and Survival by Margaret B. Jones, a.k.a a white woman named Margaret Seltzer, who reinvents herself as a half-white, half-Native orphan raised in a black foster family in South Central LA who falls into gang life. The book cover of an older black woman embracing a young white girl (a composite of stock photos from Getty) and the bad slang—“Aiight, sho nuff”—suggest “that few to no black people seem to have weighed in on the book’s publication in its years-long journey from pitch to print.” Rather, these choices indict the blinkered views held by publishing’s mostly white gatekeepers—a gate Seltzer the hoaxer waltzed on through.

The most unimaginable life experiences become not enough. In Angel at the Fence, Holocaust survivor Herman Rosenblat embellishes his true story of survival in the Buchenwald camp with a fabricated one about living off of the apples that his future wife threw over the fence. This version has the couple reuniting on a blind date in the United States years later. Again, Winfrey, queen of daytime TV and champion of fake memoirs, declared it the “single greatest love story.” Young writes: “The horror story must become a love story, an American tragedy with a happy ending.”

Collectively, our memories construct our view of history. Fake memoirs masquerading as accurate accounts of historical events sully our understandings of these moments as surely as if Pennywise the Clown had snuck in to photobomb the scene. Everything around him is rendered absurd and vulnerable to doubt by his presence. When the portrait in question concerns historical traumas such as the Holocaust, or the experience of life on an Indian reservation or as a child prostitute, Young demonstrates that this sullying isn’t simply a pathetic grab for attention. It’s a violation against all the people who were genuinely affected.

To read such a persuasive and exhaustive examination of the history and ubiquity of the hoax can leave you questioning anything that purports to be real—this is one of fakery’s most insidious consequences. Even comparatively harmless transactions like a plagiarized review tear at our collective trust. In a culture in which such bunk is so widespread, the sense that daily news journalism could be “fake”—that there is no solid ground whatsoever for truth—allows our Pennywise-in-Chief to step into the picture. Young finishes on a sobering note, acknowledging his wish to conclude his tour more cheerfully—that he could claim that we’d survived this long era of bullshit to come out the truer and wiser. But such a positive spin would be a hoax, a particularly American one in its elision of fact for the sake of a happy ending.

Bliss Broyard is the author of the story collection, My Father, Dancing, which was a New York Times Notable book, and the award-winning memoir, One Drop: My Father’s Hidden Life—A Story of Race and Family Secrets. Her stories and essays have been anthologized in Best American Short Stories, The Pushcart Prize, The Art of the Essay, and other collections, and appeared in the New York Times, Newyorker.com, Elle, Time, Medium, and elsewhere.