Geeta Dayal

Geeta Dayal

MoMA explores the convergence of art and computing in three early decades of the digital era.

Thinking Machines: Art and Design in the Computer Age, 1959–1989, installation view. © 2017 The Museum of Modern Art. Photo: Peter Butler.

Thinking Machines: Art and Design in the Computer Age: 1959–1989, the Museum of Modern Art, 11 West Fifty-Third Street, New York City, through April 8, 2018

• • •

It seems obvious today that art, design, and computing would eventually converge, but that trajectory was far less predictable in the 1950s, when the first commercial computers were introduced in the United States. A new exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art, Thinking Machines, takes art and computing from 1959 to 1989 as its focus. Film, video, music, drawings, paintings, architecture, and installations created with computers, or that were computationally inspired, are shown alongside some noteworthy designs of computing devices through the decades; most of the pieces are culled from MoMA’s own collection. The selection of the years 1959 through 1989 seems overly expansive for a show that only takes up part of one floor; some of the 1980s material, such as a Max Headroom video, distracts from works earlier in the chronology. Many of the artists selected for the show are legendary, but as an exhibition, Thinking Machines feels uneven, and the works come across as isolated from one another, at points where there should be stronger connections.

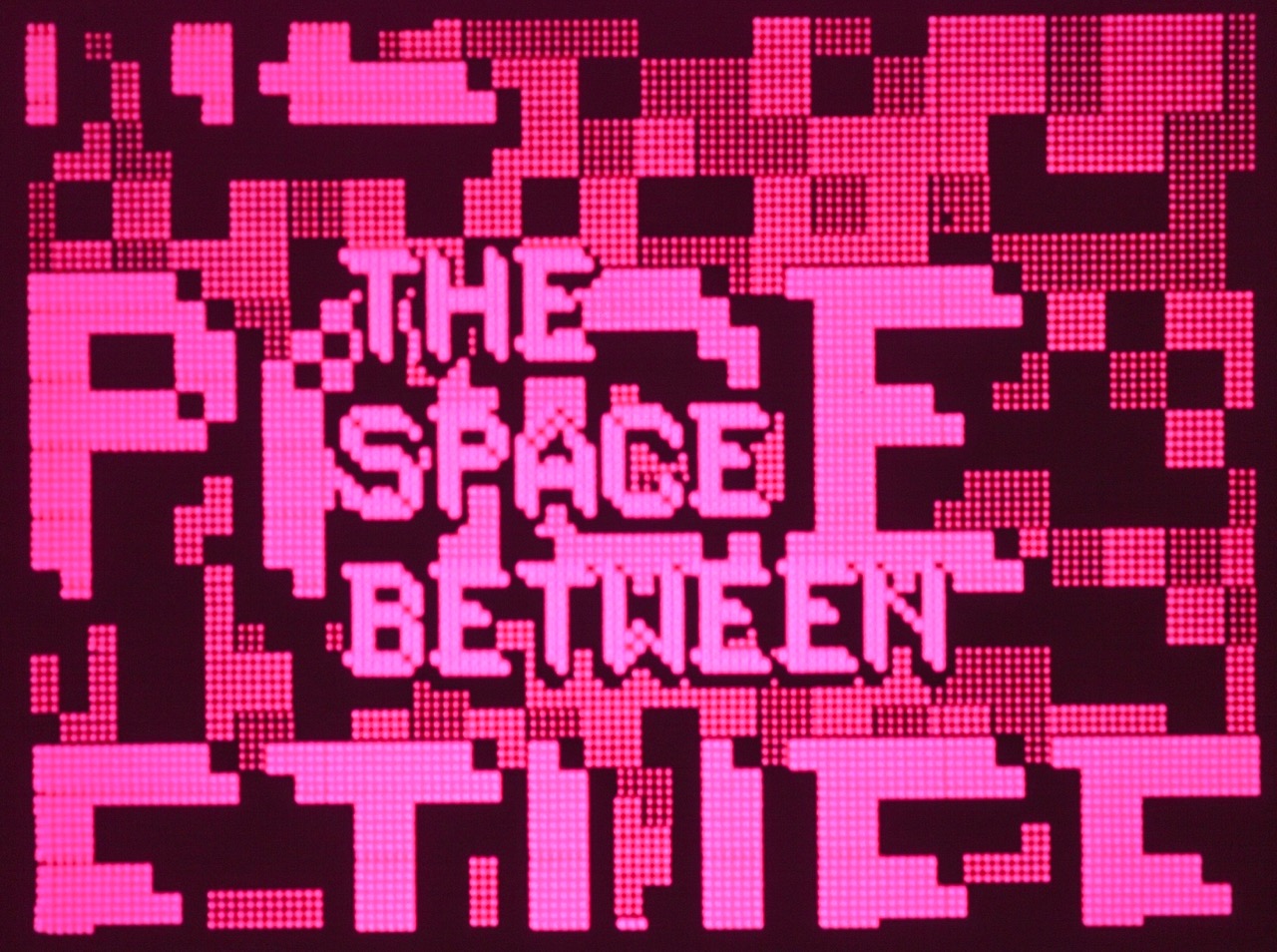

Stan VanDerBeek, Poemfield No. 1, 1967. 16mm film transferred to video (color, silent), 4 minutes 45 seconds. Realized with Ken Knowlton. Photo: Lance Brewer. Image courtesy Estate of Stan VanDerBeek and Andrea Rosen Gallery. © 2017 Estate of Stan VanDerBeek.

Many pieces are indeed outstanding—it’s hard to argue with Stan VanDerBeek’s ingenious computer films Poemfield No. 1, No. 2, and No. 3 (1967, created with the help of Bell Labs engineer and artist Ken Knowlton), or Toshi Ichiyanagi’s stark 1960 punch-card-influenced score IBM for Merce Cunningham (drawn by George Maciunas), or John Cage and Lejaren Hiller’s vibrant computer-music opus HPSCHD (1969). One problem is that we’ve seen much of this before, in more exuberant settings: various projects by VanDerBeek have been resurrected extensively, most recently at the Whitney Museum; the same Ichiyanagi score was also exhibited a few years ago in MoMA’s wonderful Tokyo 1955–1970: A New Avant-Garde; and HPSCHD was restaged in its full splendor by Issue Project Room in collaboration with other New York organizations in 2013. Renderings of vintage Olivetti computers, which echo some of the designs here, were revisited in the Ettore Sottsass show at the Met Breuer.

Mario Bellini, Programma 101 Electronic Desktop Computer, 1965. Die-cast aluminum casing. Manufactured by Ing. C. Olivetti & C. S.p.A., Ivrea, Italy. © 2017 Mario Bellini.

In this current context at MoMA, these objects seem strangely drained of life: HPSCHD, for example, was not simply a composition involving computers, but a major multimedia spectacle—including harpsichords, numerous tapes, films, and slides. Here we only see some artifacts of its existence: a copy of the vinyl record, released by the Nonesuch label; flowcharts of subroutines; and a score in faded red ink, in Cage’s own handwriting. The dynamism of HPSCHD is absent, and a satisfying sonic presentation of HPSCHD is missing too. Nearby, issues of the essential video art magazine Radical Software, established in 1970, are under protective glass, with only the covers visible—preventing us from browsing the prescient material contained within, which explored the impact of emerging technologies in their nascent stages. (You can read all of Radical Software online, on radicalsoftware.org.)

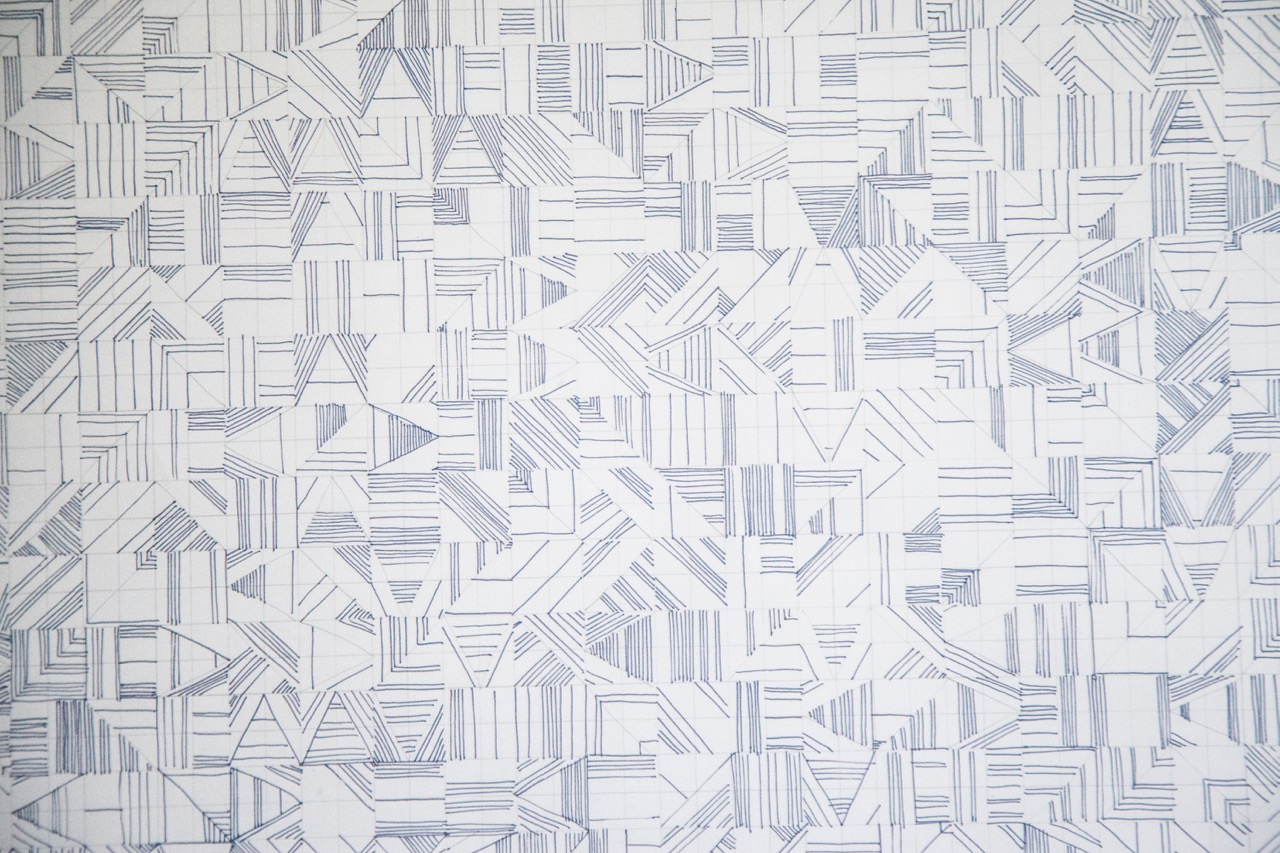

Vera Molnár, A la Recherche de Paul Klee (Searching for Paul Klee) (detail), 1971. Felt tip pen on paper. © 2017 Vera Molnár.

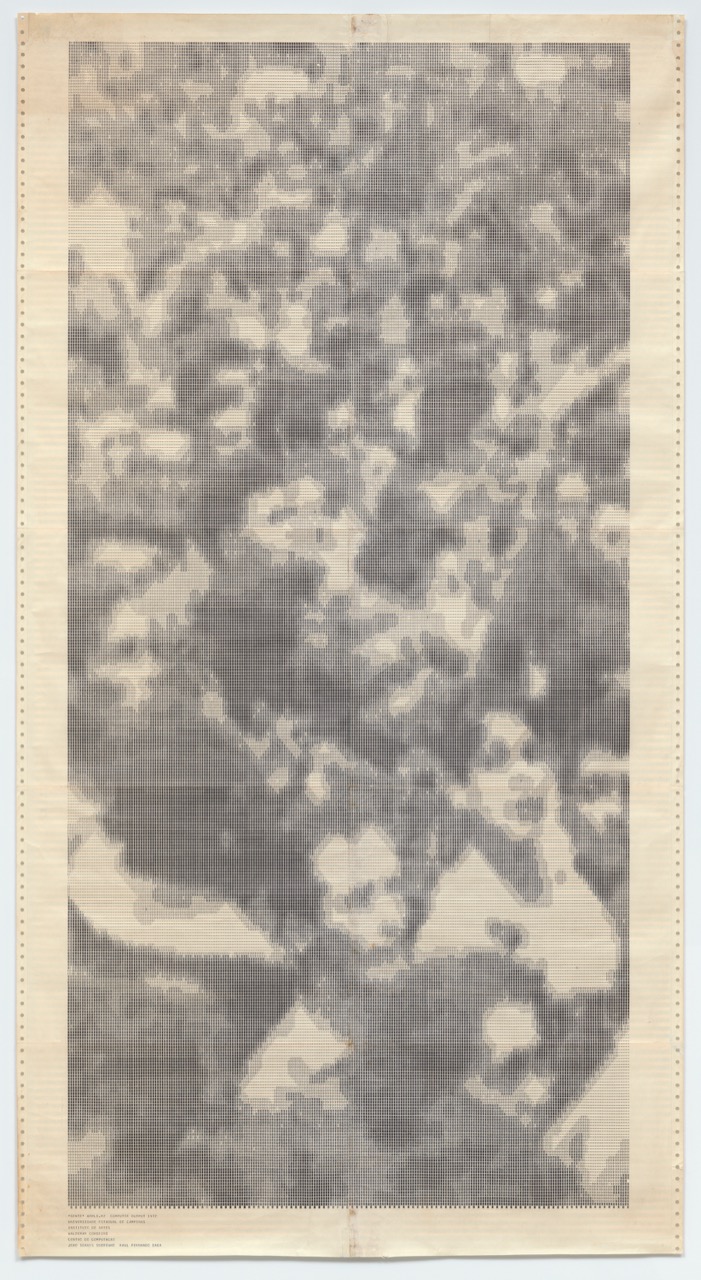

There are several works of visual art here that feel revelatory and exciting—such as Vera Molnár’s soft and exquisitely precise drawings from the 1970s and 1980s, many made with a pen plotter; Waldemar Cordeiro’s Gente Ampli*2 (1972), a computer-outputted image of a crowd that is delicate, curved, and deeply human; and Beryl Korot’s Text and Commentary (1976–77), composed of five channels of video, with intricate weavings and drawings. In contrast, some of the design objects feel played out, such as a few prominently placed specimens of Apple Macintosh computers. Perhaps a DEC PDP-1 from 1959 (on which Spacewar!, the groundbreaking early computer game, was invented in 1962), or a Cray CDC 6600 supercomputer from the 1960s—with its sleek lines and space-age style—could have been shown instead. (At the very least, it would have been more refreshing to see an Amiga, which Andy Warhol used to make digital drawings in the 1980s.)

Waldemar Cordeiro, Gente Ampli*2, 1972. Computer output on paper. 52 15⁄16 × 28 9⁄16 inches. © 2017 Waldemar Cordeiro.

The friendships and links between many of the artists in Thinking Machines also feel less palpable than they should be. Cage was one of the ultimate twentieth-century connectors, of course, and like VanDerBeek and Alison Knowles—who is represented here, via her key 1967 FORTRAN-facilitated poem A House of Dust—Cage collaborated with engineers at Bell Labs. (In addition to exploring computer music at the University of Illinois with Hiller, Cage also befriended the computer music pioneer Max Mathews, the longtime Bell Labs director of acoustics and behavioral research; Mathews, at various times, wrote code to simulate the I Ching for Cage.) But in Thinking Machines, Cage seems to be one of many lone boats in a vast ocean, rather than part of a continuum.

It makes sense that many of these artists would have known one another, if for the simple reason that many of them used the same computers in the same places. In the 1950s and 1960s, in particular, computers were a scarce commodity. Before the personal computer revolution took hold in the late 1970s, computers were generally tied to large institutions—such as universities and industrial settings. The machines were enormously expensive, lumbering behemoths, which could easily take up entire rooms. Using a computer in those days was an arcane, time-consuming process—few people had access to these institutions, and to the engineers who could operate the equipment.

It is also hard to grasp—from seeing the exhibition, in the year 2017—how subversive so much of this was when it was originally made. Early computers, of course, were not designed to be creative tools. IBM’s first commercial computer—the IBM 701, released in 1952—was known as the “Defense Calculator.” This wasn’t an accidental moniker; computers were designed with military uses in mind, as Cold War paranoia continued to escalate.

Thinking Machines Corporation, CM-2 Supercomputer, 1987. Steel, plexiglass, and electronics. Photo: Stephen F. Grohe.

Computing has a complicated history. Vintage pieces on display here as design objects, such as the guts of a control panel for an IBM 305 RAMAC (Random Access Memory Accounting Machine) from 1950, and punch cards from 1956, bring up difficult questions. The colorful tangle of wires jutting out of the RAMAC’s aluminum frame is reminiscent of a modular synthesizer, and the dense electrical mass certainly possesses a cool beauty. Nearby, a majestic black CM-2 Supercomputer from the Thinking Machines Corporation (1987), with arrays of blinking red LEDs, impresses with its slickness. But it’s easy to fetishize the enclosures, forgetting that data once coursed through them. (For instance, the RAMAC wasn’t just used for business; it was also once used by the Navy.)

Thinking Machines is a fascinating, if bumpy, ride through some of the history of computing and the arts. A more concentrated and dynamic presentation could fully reveal how vital so much of this art still is.

Geeta Dayal is an arts critic and journalist, specializing in writing on twentieth-century music, culture, and technology. She has written extensively for frieze and many other publications, including The Guardian, Wired, The Wire, Bookforum, Slate, the Boston Globe, and Rolling Stone. She is the author of Another Green World, a book on Brian Eno (Bloomsbury, 2009), and is currently at work on a new book on music.