Julia Bryan-Wilson

Julia Bryan-Wilson

Three decades after they were taken, the artist’s photographs of historical armor take on a terrifying gleam of violent ideology and elitist systems.

Zoe Leonard: Display, installation view. Courtesy the artist and Maxwell Graham Gallery.

Zoe Leonard: Display, Maxwell Graham Gallery, 55 Hester Street, New York City, through October 25, 2025

• • •

Zoe Leonard’s Display, a series of black-and-white photographs taken by the artist in the early 1990s but only recently printed, lands with uncompromising force. The negatives—pictures of historical suits of armor placed in glass vitrines—sat dormant in a box in Leonard’s studio for some three decades. Their emergence now feels less like a rediscovery than a reckoning. In the grip of the Trump era, amid the rise of authoritarian tactics and techno-futurist fantasies of invulnerability, Leonard has returned to these images with renewed urgency.

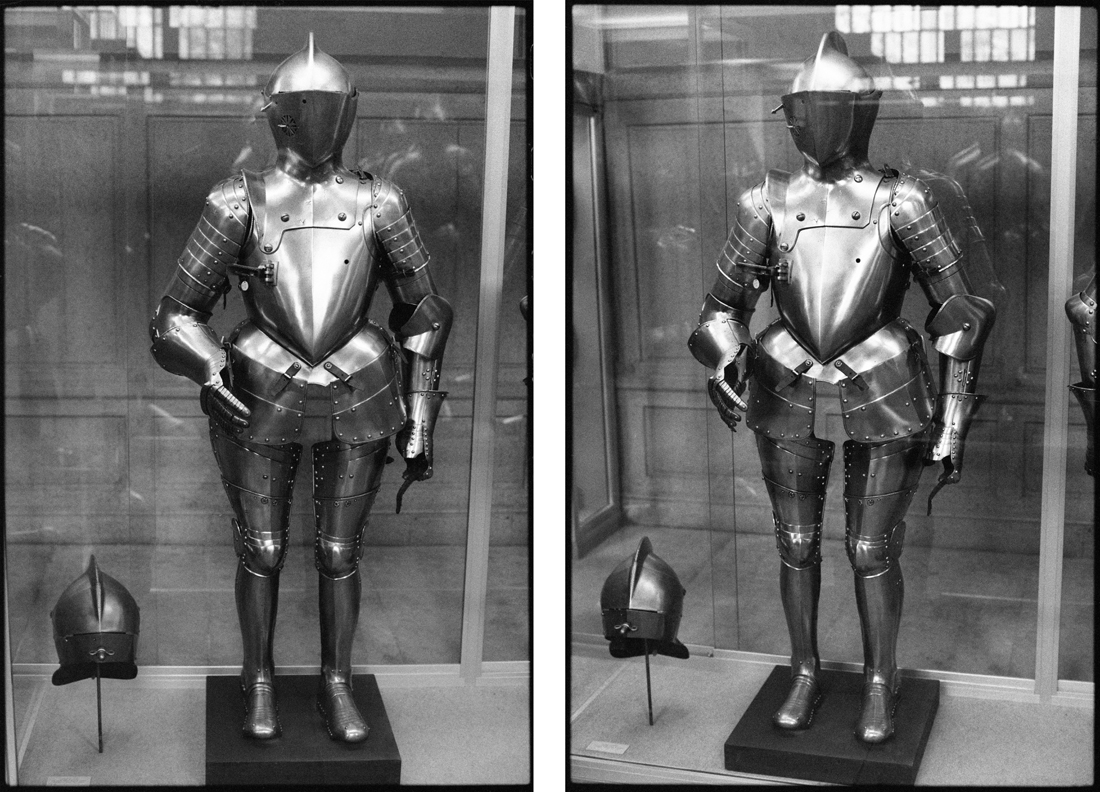

Zoe Leonard, Display IX, 1994/2025. Gelatin silver print, 19 7/8 × 14 inches. Courtesy the artist and Maxwell Graham Gallery.

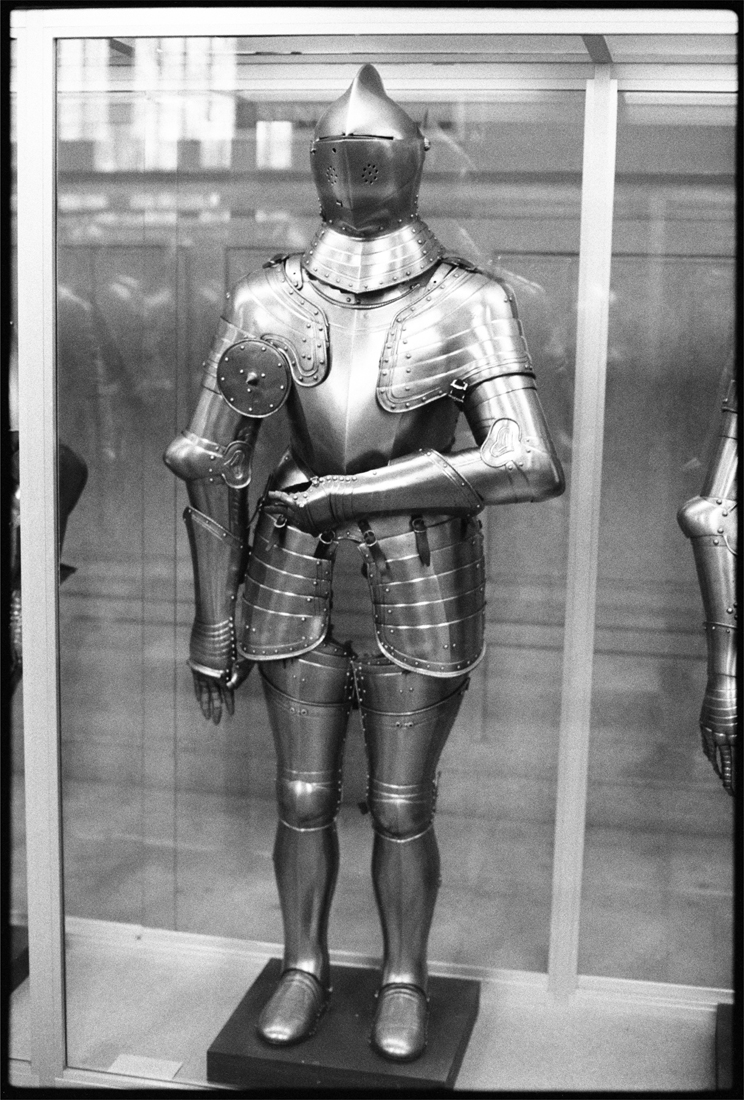

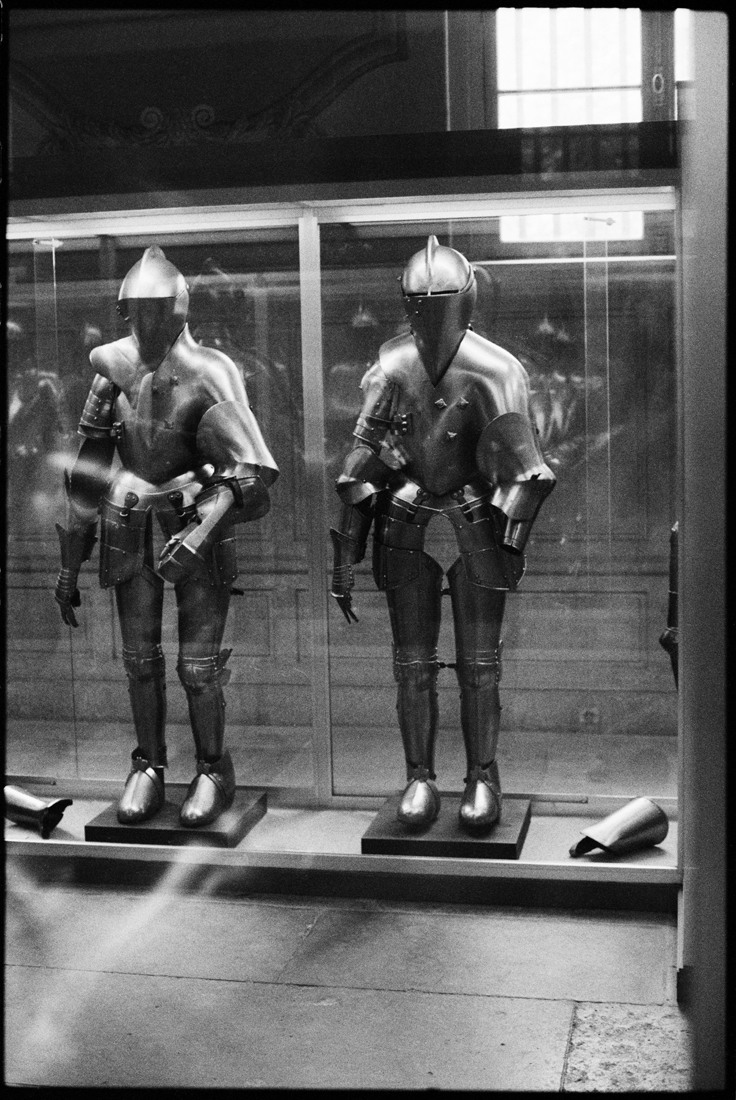

The installation at Maxwell Graham is pared down and chilling. Her six gelatin silver prints hang in the cool white gallery, each presenting metallic husks of armor. One photograph, Display IX (1994/2025), is of an ancient Greco-Roman torso cuirass with sculpted musculature and nipples, pocked with wear. The others depict entire suit panoplies from medieval Europe—swooping, petallike plates enfold the absent bodies, with articulated knees and elbows curling like the sections of pill bugs. Chest plates are adorned with shields and studded with rivets. It is difficult to imagine how one could breathe inside these exoskeletons and full-face helmets, much less how one could ride, fight, or run.

Zoe Leonard, Display IV, 1991/2025. Gelatin silver print, 33 1/4 × 23 1/4 inches. Courtesy the artist and Maxwell Graham Gallery.

Provocatively, all the suits are missing codpieces or other groin protection—Leonard’s queer feminist gaze has focused in on the structuring absence of these conspicuously gaping holes. These ensembles are cherished objects, preserved and polished by museums as treasures of European heritage. Yet Leonard emphasizes their hollowness as she observes that these relics of conquest, domination, and slaughter have become dressed up as ornament. In this, Display most obviously sits alongside other series in which the artist chronicles, with forensic precision, how gender is produced via material practices (her pictures of chastity belts, for instance, and female wax anatomical models in medical museums). The works in Display also resonate with Al río / To the river, her recent epic documentary photo project that interrogates regimes of surveillance and policed enfortressing along the US–Mexico border; here, too, she steadies her attention on something disturbing as a way to pry its systems apart.

Zoe Leonard: Display, installation view. Courtesy the artist and Maxwell Graham Gallery.

In the photos of Display, the labels in the vitrines are blurred or out of frame; dates, provenances, and technical classifications are withheld. Leonard is less interested in documenting or categorizing armor as artifact than she is in exposing its optics—what ideologies armor projects, and what violences it obscures. By pressing her camera up against the glass, she turns the vitrine itself into part of the image: reflective surfaces and glare from natural light are captured in her compositions. In the promotional postcard, she includes a glimmer of her own ghostly body, though her face disappears, occluded by the apparatus of the camera. Her presence is both insistent and self-effacing, registering the voyeurism of looking while refusing the transparency of vision. Just as the eye-slit of an armored helmet—the ocularium—offered only the narrowest glimpse onto the battlefield, photography can obstruct as much as it can reveal. The most telling piece in this regard is the diptych Display V (1991/2025), a near-identical pair hung closely together. The two pictures vary only in the angle at which they were taken, indicating that Leonard has shifted her perspective by a few inches. Thus, how we see is as much at issue as what we apprehend.

Zoe Leonard, Display V, 1991/2025. Two gelatin silver prints, each 33 1/4 × 23 1/4 inches. Courtesy the artist and Maxwell Graham Gallery.

The “knight in shining armor” was once the storybook image of male heroism, a metal carapace the garment of choice for fictional chivalrous warriors of yore. But Leonard presses on its absurdity. Most of these suits were exorbitant luxury goods, reserved for aristocrats, elite landowners, and well-paid mercenaries. They were expensive markers of prestige worn in jousts, tournaments, and pageantry as much as in battle. They could be clumsy, clankingly loud, heavy, smelly, and unbearably hot. And for all their engineering, they did not protect against mass death in combat. Ordinary soldiers—bare-skinned peasants rushed into the front lines—died unarmored, as expendable in wartime as they were working the fields. The armor might gleam, but it cannot mitigate the dark futility underneath.

Zoe Leonard, Display III, 1991/2025. Gelatin silver print, 33 1/4 × 23 1/4 inches. Courtesy the artist and Maxwell Graham Gallery.

Leonard’s photographs seethe with the recognition that metal shells of various kinds still preoccupy us. The ruthless pursuit of invulnerability, the parade of force as force itself, has not disappeared—it has metastasized. It is there in the impunity suggested by the ICE agent’s bulletproof vest and mask, shielding the face from public shame. It is there in the grotesque corporate phenomenon of Tesla’s Cybertruck, the laughably sinister vehicle whose dull-gray envelope promises high-tech defense and callous disregard for ecological devastation. Leonard’s medieval armor becomes an allegory for the present, illustrations of depressing continuity rather than curiosities from a distant past.

There is also, unmistakably, a politics here. Leonard took these photographs between 1990 and 1994, during the early days of the AIDS crisis before treatments existed, when she was engaged in direct action and collective resistance against astounding governmental neglect. Masculine bodies were then figured as both impenetrable and terrifyingly permeable, ravaged by a virus that ignored wealth or status. To look at these suits now is to register that porousness, for they indicate bodies encased and securitized, but also trapped. Suffocating. With their emphasis on fragility within the enclosure of enclosures, the photographs are claustrophobic, tough, and wise.

Zoe Leonard, Display I, 1991/2025. Gelatin silver print, 54 × 37 3/4 inches. Courtesy the artist and Maxwell Graham Gallery.

What makes Display so arresting is that it neither romanticizes nor historicizes its subject. Instead, Leonard trains her lens on the contradictions of armor: strength meets weakness, hard covering meets yielding flesh, fortification meets vulnerability, shine meets stench. The suits were tailored with unimaginable skill yet proved useless against the inevitable accelerations in weapons design. Formally, the photographs amplify this tension. The grain of the prints echoes the patina of the armor, collapsing photography’s material substrate (gelatin silver, too, is based in metal) into the subject it depicts. Dust, scratches, and flecks on the negatives sit alongside the rivets, dimples, and knobs of the armor, making it hard to tell which marks belong to the corrosions of time or usage, and which belong to the image.

In the end, Display is not about armor, or even about museum practices, so much as it is about the endurance of a worldview: that conquest can be aestheticized as spectacle, that depersonalization can be the key to victory, that power can be made decorative. Leonard refuses the seduction of the glittering, fascistic corpus. Thirty years later, these images have only grown sharper and more unbearable to confront. She gives us the void beneath the gleam, the absence behind the mask. Her photographs evoke fortified yet empty legions who have been waiting, dormant, and are now ready to seize their moment.

Julia Bryan-Wilson teaches contemporary art and LGBTQ+ studies at Columbia University and is curator-at-large at the Museu de Arte de São Paulo. With Natalia Brizuela, she is curator of Lotty Rosenfeld: Disobedient Spaces, which opens at the Wallach Art Gallery in November.