Ania Szremski

Ania Szremski

Wateryworld: language and its faults make for a story of amphibolous feelings in the inaugural installment of Jon Fosse’s new trilogy set in a small fishing town.

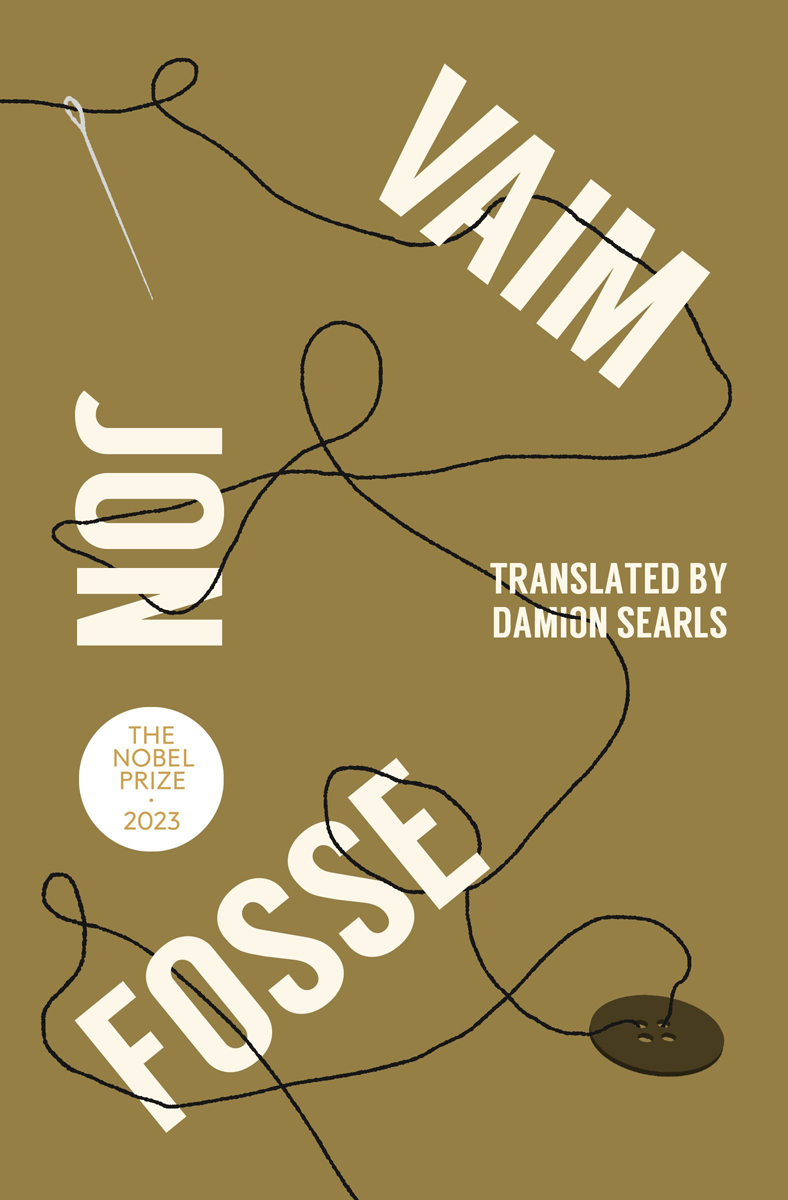

Vaim, by Jon Fosse, translated by Damion Searls,

Transit Books, 120 pages, $25.95

• • •

“Yes” and “no” are two of the most-used words in any language, and two of the earliest learned—but they’re also weirdly hard to categorize, at least in English, in which these crucial affirmations and negations, which seem so clear, are surprisingly ambiguous when you try to define them as parts of speech. Are they adverbs? Interjections? Nouns? Imperatives? They can be all of those things, but in certain usages, such as when they’re spoken alone, maybe in answer to a question, or a call, an invocation, some linguists classify them as a “pro-sentence” (also known as a “minor sentence”). Sort of like how a pronoun stands in for a subject, saying “yes” or “no” deletes the subject from the statement altogether, renders the subject null.

This proposition of the minor sentence is particularly apt when considering Nobel-winning superstar Norwegian author Jon Fosse’s novel Vaim (now available in exhilarating English translation from phenom Damion Searls), which is a book of “yes” and “no,” particles that often appear right next to each other in the same thought: “yes, I was hoping to meet someone, yes, someone to share my life with, as they say, but no, not this time, as they say, yes . . .” This, from the first narrator we meet in this opener to a trilogy set in the fishing town of the title, a volume as slim as Fosse’s famous Septology is long. The protagonist in question goes by Jatgeir, which we eventually learn is a nickname—apparently he said “yes” so much as a child, “ja, ja, jatta,” it became appended to his given name, Geir. Now, somewhere in his lonely ageing, his affirmative nature has become one of doubt and backtracking, he dances between “yes” and “no” in a single thought, but to whom he is making these utterances is not totally clear, just to himself I suppose—a null subject, his grasp on reality unsure, his relations to others practically extinct, his actual physical existence, at one point, a question mark.

Jatgeir wavers between “yes” and “no” and worries about finding the right words and also worries people are both snookering and laughing at him as he endeavors (twice) to buy a spool of black thread and a needle for sewing on a displaced button. Note the color of the thread; and note that the tie of one of the snookering salesmen is pink; the water in the bay is blue; the buoy in that water is red; Jatgeir’s childhood home (all the men in this novel, orphaned, live in their otherwise empty and entirely unkempt childhood homes) is white; his overgrown hair and beard were always black but lately shot through with gray; and these constitute the entirety of the colors summoned in the 120 pages of this book, as plainly as that, like paints applied straight out of the tube, not a specific hue nor shade considered, just the bald, stark name of each. This adds to the dreamlike unspecificity of a text that does not contain a period—like Septology, it is constituted of one mounting sentence guided only by paragraph breaks, commas, and the occasional question mark, trailing off into negative space at the end of one chapter and picked up by a different narrator in the next. It’s a sentence whose only specificity comes in the description of Jatgeir’s motorboat, Eline, the spaces of which are described in ecstatic detail. The boat was named for the unspoken love (though he personally would not use that word, no, but yes, he loved her) of his life, who left their hometown of Vaim as a girl, but who returns to Jatgeir, mysteriously and completely unbelievably, one night in their middle age.

The night she boards Jatgeir’s boat, fleeing her husband seemingly on a whim, the word “yes” is finally pronounced somewhere outside of Jatgeir’s internal narration, and it is pronounced in a chorus of different ways:

Yes, she said

and that yes kind of sank into me, yes, it was almost like I swallowed the word and it got stuck in my stomach, and the yes was like the answer to a huge question

Jatgeir says it too, yes, loud and clear, and then he says her name, Eline, also “loud and clear and I couldn’t help it, there was something like a trembling love in my voice, or something like longing, more than anything it was like I’d said the name Eline in a pleading voice, and I didn’t mean to, not at all, it just came out like that, I couldn’t help it, so much longing . . .”

Years before Eline stepped onto his boat, back when he had first named it for her, majuscule letters on its side, and people laughed at him for it, the men of the fishing village started calling him Eline. In Vaim, not a soul knew Eline’s real name, Josephine, and when she married Frank, the people of the town to which she had fled started calling her variations of “Frank.” None of the protagonists are known by their “real” names, with the exception of Jatgeir’s one and only friend, Elias, who narrates the second of the three chapters, and is also the second of Vaim’s principle characters to casually die, right in between Jatgeir and Eline. We learn of his death almost in passing in the third, final chapter, narrated by Frank, who was born Olaf, but who had allowed Eline to drunkenly rechristen him, and whose first boat, Elinor, recalls her nickname, but will be replaced by a second boat that he will also call Eline. This trio of men all resemble each other to an uncanny degree; and all (including Elias, whom Eline effectively bans from Jatgeir’s life) are subject to the will of this phantasmic woman, ghostly and barely sketched out, even despite all her power.

Vaim is full of doubts about language and communicability, ambivalence around word choice; narrators grasp mutely at those things and feelings that cannot be articulated, and events that in a traditional novel would be major climaxes transpire almost without comment. Language does not build a world here—its faults make the world’s solidity crumble. Instead of the comfort of object permanence, in Vaim, we’re carried along in the anxious mutability of drift, wake, current, float.

It is also a book of amphibolous belief. Jatgeir mentally recites “Our Father” every night before he goes to bed. He’s not sure why—if it’s out of faith, or habit. Elias goes to the prayer house sometimes, also not sure why—if it’s out of faith, or loneliness. Forget God—can we even believe in Vaim? For the town is not a real place, outside of and maybe even inside of this book. Eline tells Jatgeir that, as far as Frank was concerned, “it was like Vaim didn’t exist for him, like there wasn’t anywhere in the world called Vaim, like Vaim was just a dreamworld, but both of them, yes, both she and Jatgeir knew that Vaim was a very real place, they had both grown up in Vaim, so for both of them the town of Vaim was one of the realest places in the world, even if you had to wonder just then at the moment what was real and what wasn’t . . .” The most concrete and real-seeming aspect of this story is the micro-place of Jatgeir’s motorboat, but even then, he isn’t sure boats are really part of “reality” or if they themselves are dreams. In this watery world of limited palette and vacillating conviction, it’s a question that can’t be answered with “yes” or “no,” but of course the answer is also both, yes, and what’s left is a river of a sentence whose subjects are deleted.

Ania Szremski is the senior editor of 4Columns.