Andrew Chan

Andrew Chan

A new solo album showcases the irresistible pleasures of the country artist’s vocal powers.

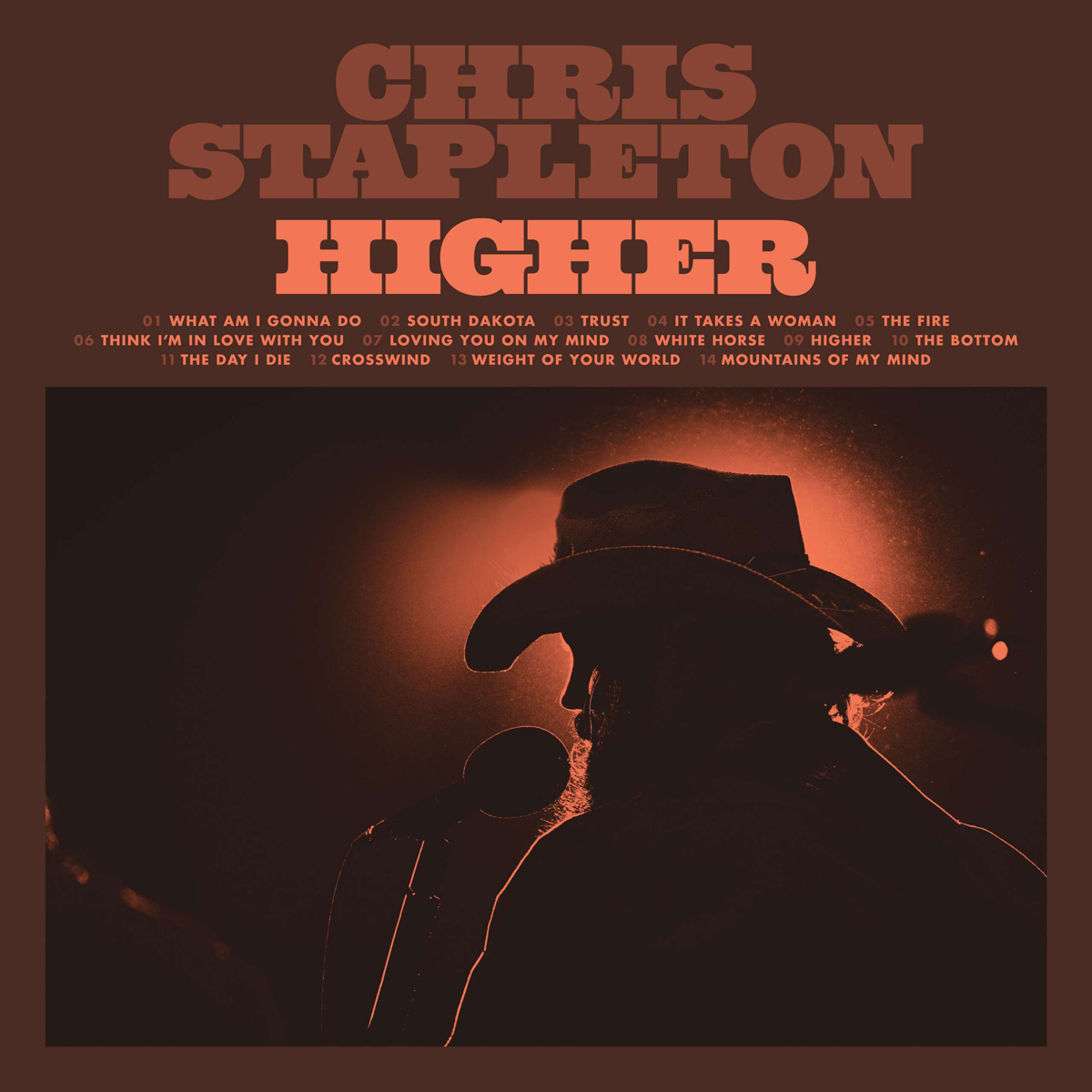

Higher, by Chris Stapleton, Mercury Nashville

• • •

Like nothing else in the popular arts, songs are efficient little engines of nostalgia. No movie or book can conjure the feeling of a bygone era with as much aching immediacy as a tune performed in a retro style. That’s why, no matter how critics may dismiss the 1970s-funk replicas of Silk Sonic or the Sinatra-lite of Michael Bublé, there will always be listeners who find the familiarity of these performers hard to resist. And, as the writer Ted Gioia has noted, old sounds hardly require updated guises to be successful these days; more than ever, audiences are favoring back catalogs over new releases, suggesting that music consumption is a vehicle for emotional regression, a way of clinging to illusions of a prelapsarian past in these overwhelming times.

When Chris Stapleton released his debut solo album, Traveller, in 2015, he was hailed as a bearer of tradition in country, a genre perennially fixated on questions of classicism vs. modernity. The Kentucky-born artist had gotten his start in Nashville as the front man of the bluegrass band the SteelDrivers, giving him a rural, down-home credibility even as he wrote songs for some of country’s slickest stars, including Luke Bryan, Tim McGraw, and Kenny Chesney. At the time, when male country artists seemed trapped at an endless tailgate party, Stapleton’s rootsy, moody aesthetic could have relegated him to the genre’s fusty Americana wing. But eight years and just as many Grammy Awards later, his work has remained consistent while becoming about as broadly palatable as country gets, increasing the genre’s appetite for the vintage sounds he champions.

Higher, Stapleton’s fifth solo album, underscores the pleasures of his professionalism—even when it tips into flagrant predictability. Many of the record’s standout tracks are almost embarrassingly basic, as if the musician were offering further proof that his powerful, cavernous voice can sell any melody. The opener, “What Am I Gonna Do” (a collaboration with one of country’s greatest singer-songwriters, Miranda Lambert), ambles along steadily, ruminating on lost love with minimal histrionics and no catharsis. The tossed-off detail of a “jukebox with a neon glow” playing a Merle Haggard oldie implies that music can neutralize pain by offering precedents, casting heartbreak as just the way of things. By the end of the song, you realize the bulk of it consists of the relentlessly interrogative chorus. The singer never gets enough distance from his own litany of questions (“What am I gonna be?”; “What am I gonna drink?”) to even start to answer them for himself. Any conspicuous shift in the music would be at odds with the hero’s state of mind, indicating a change he isn’t ready for.

Such reticence is notable, considering that Stapleton is beloved primarily for his take-no-prisoners singing style. Combining a burly baritone reminiscent of Haggard with the swooping dynamics of a soul belter like Solomon Burke, his voice is a magnetic force, and invariably becomes the centerpiece of anything he records. I was first made aware of him by an R & B fan who pointed me to Stapleton’s performance of the country standard “Tennessee Whiskey,” which hinges on a startling passage of fast, bluesy melisma that doesn’t exist in any previous rendition. White singers influenced by African American vocal style are a dime a dozen, but it’s still rare to hear such ostentatious boundary-crossing in the realm of mainstream country, which consistently marginalizes Black artists and is often perceived as a haven for revanchist white politics.

Stapleton’s intimacy with the classic-soul idiom doesn’t seem calculated or affected, and on Higher, he applies it with the matter-of-factness of someone who understands country and R & B to be twin genres. Moving nimbly between head-nodding funk and gospel testimony, “Think I’m in Love with You” sounds like an unreleased outtake from Al Green Gets Next to You, an album Stapleton paid tribute to with his persuasive 2022 cover of “I’m a Ram.” Green (who, incidentally, covered Hank Williams and Willie Nelson in his heyday) is one of the subtlest of canonical soul singers, and Stapleton’s indebtedness to him is made all the more evident in Higher’s title track, which emphasizes the most delicate part of the singer’s falsetto, and in the bongo-driven “The Fire,” which evokes Green’s brand of mellow, meditative seduction. Perhaps the key lessons that Stapleton has learned from Green are that vocal virtuosity does not preclude a lightness of touch, and that the biggest gestures sometimes benefit from an unfussy delivery.

One exception to this approach is “White Horse,” a rare moment on the album when Stapleton makes a flashy show of effort. He has never pulled off a noisy, stadium-scale rocker quite like this before, and from measure to measure and flourish to flourish, it’s exhilarating. Against a backdrop of turbid electric-guitar riffs, ferocious percussion, and hints of Hammond organ, Stapleton holds his own at the eye of the storm, but the lyrics cut against all the pomp and grandeur: he’s essentially admitting to a kind of impotence, unable to fulfill his woman’s fantasies of a hypermasculine cowboy hero. The aggressive production is a self-conscious distraction from the protagonist’s inadequacy; ramped up by a couple of surging tempo changes, the song comes off like Fleetwood Mac’s “The Chain” by way of Lynyrd Skynyrd.

Higher contains a few more instances of tension and hesitation, and yet, for my money, the album is more compelling when it opts for unadulterated sentimentality. (After all, before Stapleton began adopting elements of an outlaw persona, the artist he tried hardest to emulate was Vince Gill, the most romantic of male country stars.) The wistful ballad “The Day I Die” has all the trappings of a throwaway—it’s an extremely conventional retread of the “I’ll love you till I die” formula from George Jones’s “He Stopped Loving Her Today,” which describes a man’s death as the only way out of his ironclad devotion to his soulmate—but Stapleton’s voice has never sounded more beautiful. While we often hear him singing at the crackling edges of his instrument, here his tone is round and pure, and it becomes even more intensely resonant as he sustains the long notes of the chorus, ornamented by a whiny pedal steel guitar and buoyed by the gorgeous, understated harmonies of his wife, Morgane Stapleton (a coproducer of the record, which is also dedicated to her). As solid as much of the album is, it’s little more than a framework for moments like these, in which talent, straightforwardly deployed, steps into the present tense, rendering questions of nostalgia beside the point.

Andrew Chan is a writer and editor living in Brooklyn, New York. He is the author of Why Mariah Carey Matters, published by University of Texas Press.