Johanna Fateman

Johanna Fateman

Girls in white dresses with blue satin sashes, but no great men among the modernist painter’s favorite things.

Marie Laurencin: Sapphic Paris, installation view. Courtesy Barnes Foundation. © Barnes Foundation.

Marie Laurencin: Sapphic Paris, curated by Simonetta Fraquelli and Cindy Kang, Barnes Foundation, 2025 Benjamin Franklin Parkway, Philadelphia, through January 21, 2024

• • •

“Cubism has poisoned three years of my life, preventing me from doing any work,” said the French painter Marie Laurencin, exaggerating, in 1923. She added, with regard to the leading names of her circle, that “as long as I was influenced by the great men around me, I could do nothing.” But by then, she’d already found her antidote to the prevailing style of her peers. Before the decade’s start, she’d freed herself from the bog of the male avant-garde’s “aesthetic problems” (as she called their formal preoccupations) to pursue her art’s defining subject—a gauzy, flower-scented world of women and their animal companions. She rendered this semi-mythic realm, which mirrored or referred to aspects of reality, with the savvy attitude of a recovered Cubist toward principles of anatomy and pictorial space. And her soft-focus, desaturated approach—she used an almost grotesque amount of white paint—effortlessly filtered men out.

Marie Laurencin: Sapphic Paris, installation view. Courtesy Barnes Foundation. © Barnes Foundation.

Laurencin’s vision, with all its captivating eccentricities (the morose eroticism of her grisaille figures; her vaporous passages of pastels; her mix of autobiographical works, society portraits, fêtes galantes starring Grecian nymphs, and forays into décor), was celebrated in its day and, for the most part, quickly forgotten—until recently. Now, a momentous précis of her career at the Barnes Foundation arrives like a breath of fresh air, or a cloud of perfume, during the long season of the artist’s most famous friend: that is, amid a string of major international exhibitions marking the fiftieth anniversary of Picasso’s death.

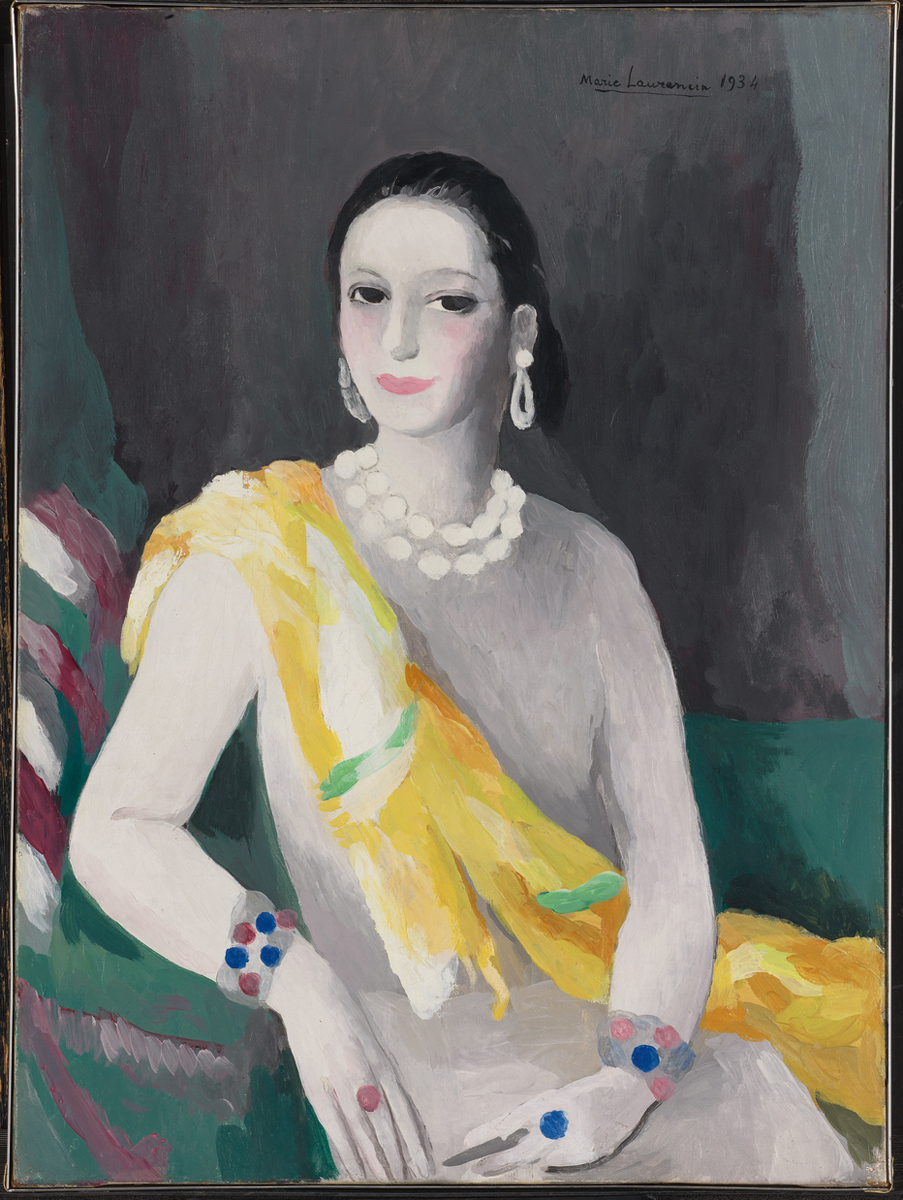

Marie Laurencin, Portrait of Helena Rubinstein (Portrait de Helena Rubinstein), 1934. Oil on canvas, 33 × 27 inches. © Fondation Foujita / Artists Rights Society / ADAGP.

In Laurencin’s well-timed new visibility, there is an implicit critique of a particular traditional art-historical narrative (i.e., her exclusion from it), but Sapphic Paris, as this transporting retrospective is titled, makes a more ambitious argument very beautifully. It presents a notion of the sapphic as not (only) a synonym for lesbian, but as a modernist aesthetic and set of strategies that Laurencin’s oeuvre uniquely reflects. The exhibition achieves the sense of an alternative, overlapping women’s avant-garde through the representation of the painter’s social circle and professional life—from the lesbian writer Natalie Clifford Barney’s salons to the presumably heterosexual women gaining professional prominence in the interwar years (Coco Chanel and Helena Rubinstein, for example) who commissioned portraits by Laurencin. And the final essay of the accompanying catalog, by scholar Rachel Silveri, describes the distinctly queer-modernist attributes of Laurencin’s work, particularly her appropriation of classical themes and her hyperbolic strain of femininity, as modes of encryption—elements that today read as more unequivocally queer, or as camp.

Marie Laurencin, The Woman-Horse (La femme-cheval), 1918. Oil on canvas, 24 5/16 × 18 7/16 inches. Courtesy Musée Marie Laurencin. © Fondation Foujita / Artists Rights Society / ADAGP.

The exhibition, spanning 1904 to 1950 (Laurencin died in 1956), unfolds in smart sections on colored walls—pistachio, rose, and lavender-gray among them—beginning with a group of self-portraits. Included are works from her time as an art student at the Académie Humbert (where she met Francis Picabia and Georges Braque), as well as two of the exhibition’s most remarkable paintings, both early canvases in her mature style. In the first, The Woman-Horse (1918), one of her most reproduced images, Laurencin depicts herself not as the being that the title suggests but as an un-horsey something else, combining mundane features (a frizzy bob, blunt bangs) with strange ones (a sculptural headdress of white pyramids). Two elongated hands resemble the composition’s pair of birds, in a favorite shade of Laurencin’s—a pasty hydrangea blue. One perches on the paintbrush the artist holds as she stands before a muddy cameo-pink canvas and regards the viewer with a knowing gaze, undistracted by the jumping dog in the shadowy lower left.

Marie Laurencin, Women with a Dove (Femmes à la colombe), 1919. Photo: Jacques Faujour / CNAC/MNAM, Dist. RMN-Grand Palais / Art Resource. © Fondation Foujita / Artists Rights Society / ADAGP.

Birds often alight in Laurencin’s pictures. Her lover, the fashion designer Nicole Groult, suggests, in a 1915 poem sent to the artist, that her body was composed of them: “Your eyes are blue birds / Your breasts are white birds / Your lip is a fire bird . . . ” And in Laurencin’s portrait of them as a couple, Women with a Dove (1919), the title’s bird seems to have been summoned by their touch. (Laurencin, who famously had a long relationship with Guillaume Apollinaire, was at that time married to the painter Otto von Wätjen. His German citizenship, and thus hers for the duration of their marriage, resulted in her exile to Spain at the outbreak of WWI, where she began her affair with Groult.)

Marie Laurencin: Sapphic Paris, installation view. Courtesy Barnes Foundation. © Barnes Foundation. Pictured, far left: Portrait of Mademoiselle Chanel (Portrait de Mademoiselle Chanel), 1923.

The curators, in their accompanying essay, quote Jean Cocteau regarding Laurencin’s animals to theorize a likely significance for their presence. Beyond their possible symbolic meanings, they signal a more profoundly animalic, magical feature of her work: “A painting by Marie Laurencin watches and listens like a roe deer. If a person who does not like animals, if a hunter approaches, the painting disappears.” Cocteau, who was gay, was perhaps pointing to the coded content of the artist’s work. Laurencin’s diaphanous, decorative charm appealed to a wide audience, while the absurd surplus of gendered things—the pink, the bows, the dancers, the scarves curling into arabesques—telegraphed to those in-the-know that the same-sex intimacy depicted was not always platonic.

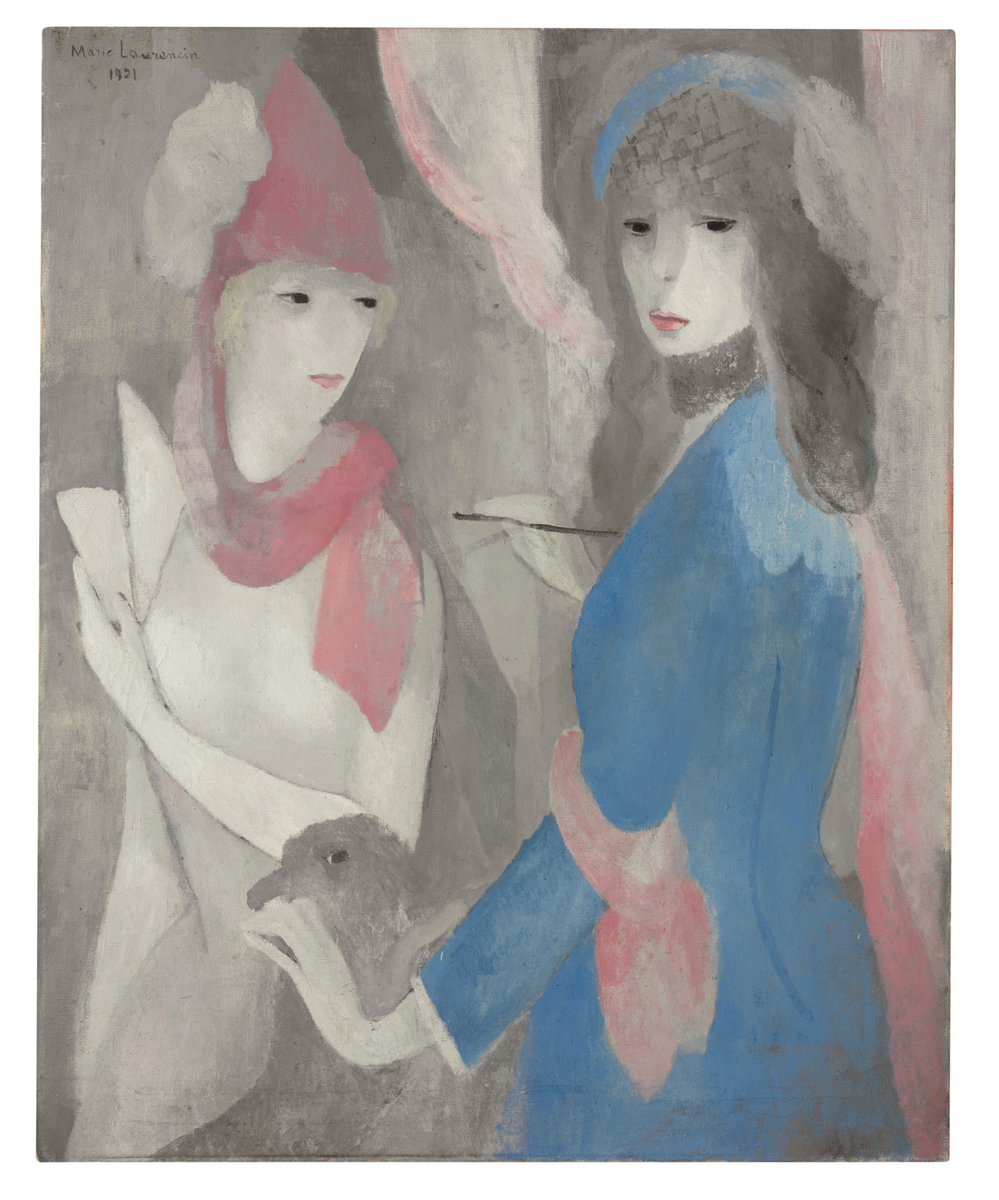

Marie Laurencin, Woman Painter and Her Model (Femme peintre et son modèle), 1921. Photo: Christie’s Images / Bridgeman Images. © Fondation Foujita / Artists Rights Society / ADAGP.

A dog also appears in Woman Painter and Her Model (1921), the other of those two extraordinary compositions at the exhibition’s start. It might be better suited to the last stretch, “Sapphic Modernity,” but it was wise to place it at the beginning; it so deftly sets the stage, gets at the importance of what Laurencin was doing—at least initially. Woman Painter is a novel depiction of artist and muse, both shown upright and clothed, equal in stature, from an era where Pablo-matic studio norms, hierarchies, and modes of representation reigned. Spatially tricky, the hazy scene—which, like The Woman-Horse, is a sooty monochrome but for chalky accents of dark periwinkle and Pepto—makes their exact setup unclear. Though the wall label states otherwise (“The artist points her paintbrush at the model”), I thought that the model was shown indirectly, on a canvas within the canvas, the painter looking over her shoulder to observe her subject posing, outside of the frame—exactly where I was standing, in fact. This viewer-implicating, egalitarian triangle thrillingly anticipates the issues wrestled with by figurative painters of the women’s art movement, which was then half a century away.

Marie Laurencin: Sapphic Paris, installation view. Courtesy Barnes Foundation. © Barnes Foundation.

In later years, as Laurencin’s palette brightened, it seems her power dimmed. The work is still gorgeous, or even more gorgeous, in a way—see, for example, the dreamily simplified Rococo style of Ballerinas at Rest (ca. 1941) or the Brobdingnagian bouquet of Fairy Flowers (1950)—but it also feels somewhat rote; it’s sapphic genre painting that’s lost its edge. Arguably, she lowered her sights, accepting the success of a one-trick phenom or celebrity of sorts, affecting naivete (“it’s better to pass for stupid,” she once advised), abandoning avant-garde aspirations to rupture or innovate. Alternatively, she didn’t try to play that game; early on, she decided not to—that was the point.

Marie Laurencin, Women in the Forest (Femmes dans la forêt), 1920. © Fondation Foujita / Artists Rights Society / ADAGP.

Laurencin was not a hero, and didn’t want to be, but emerging counter-accounts of early twentieth-century French modernism need not search for one, I think. Sapphic Paris does something better, presenting new terrain to map as well as a singular body of work. If you are, per Cocteau, a person who likes animals—not a hunter—the sickly pinks and unsmiling eyes of these paintings, both too pretty and somehow feral, might be a balm; their rare amassment an unmissable occasion. Or, for when you’re feeling sick of great men, a dose of Laurencin is at least a sweeter kind of poison.

Johanna Fateman is a writer, art critic, and musician in New York.