Andrew Chan

Andrew Chan

The musician’s slim new album gears back the bravado.

Kanye West, ye, G.O.O.D. Music/Def Jam

• • •

A natural-born maximalist, Kanye West tends to approach his albums as monuments of sound. Even when he’s at his most sparse and spacious—as on the plinking intro of the 2010 single “Runaway,” or in the cathedral-like hushes of the 2016 track “Ultralight Beam”—he dials down the volume only as a prelude to more and more excess. But on his new album, ye, the quiet moments threaten to overwhelm the noisy ones. Beats drop out for seconds at a time; whole sections ride on the reverberations of two or three notes; vocal lines are accompanied only by faint dribbles of instrumentation. We wait for the music to fatten with rich, quirky details, only to discover that most of the songs end almost as soon as they hit their mark.

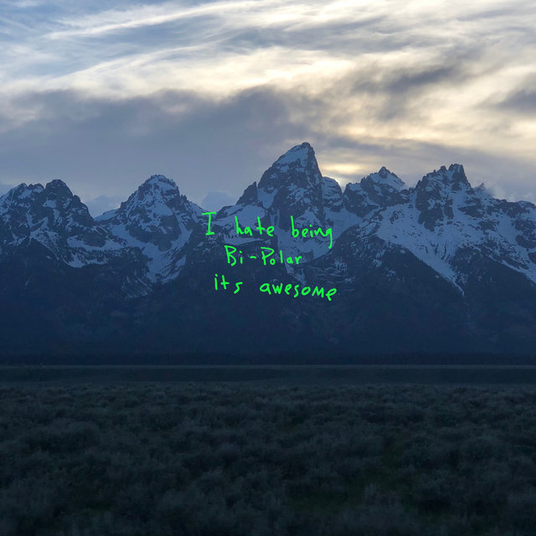

This uncharacteristic restraint carries symbolic weight in light of West’s recent flirtations with Trumpism. Ever since he threw his Twitter support behind the president, donned a MAGA cap, and called slavery “a choice,” we’ve been praying for him to shut up. When was the last time music fans felt the sting of an idol’s betrayal this deeply? It’s devastating to look back at what Kanye once meant to a generation of hip-hop heads. Those who can recall the stark divisions in turn-of-the-century rap—the dominance of the gangsta ethos in the 1990s, followed by the increasing marketability of bohemian, “conscious” MCs—have long regarded him as the genre’s great bridge-builder. The Cinemascope majesty of his first three albums felt expansive at a time when the conventions of mainstream hip-hop—hard-knocking beats, gritty tales of street life, overly familiar samples—had reached a dead end, and his sound has been agile enough to accommodate the warring strands of his personality: nerdiness and superficiality, tenderness and callousness, traditionalism and innovation. In a chicken-scratched line on ye’s cover, the artist comes out as bipolar, which fans might have already gleaned from the astonishing mood swings of his discography.

Much of the ink spilled over this new album has concerned the question of whether art can ever really redeem its maker. But it should be obvious that there’s no honest path to forgiving such odious politics, especially when the offender has never bothered to own up to the transgression. Now that we can no longer absolve West as some kind of necessary evil, a Band-Aid-ripping truth-teller in an age of PC propriety, there’s a certain comfort in watching him shrink back from his own grotesque bravado. In the context of a career that has always used genius as a bludgeon, it’s tempting to read ye’s aesthetic modesty as a tail between the legs. For the first time in his creative life, West isn’t trying to impose the greatest album of all time on us. At seven tracks and twenty-three minutes, ye can barely be called an album, and from the start, the sound comes off groggy, a little defeated. For those looking to dismiss the rapper as a has-been unworthy of all this hand-wringing, such lethargy might read as proof that his extraordinary reign has reached an end. But for those hoping for signs of a still-intact talent, comparisons to Sly and the Family Stone’s There’s a Riot Goin’ On—an ennui-filled masterpiece from a once-exuberant artist—are there to be made.

Ye doesn’t have a lot of fight in it, but West does start out by at least going through the motions. He’s in shock-jock mode with the first track, “I Thought About Killing You,” a confession of forbidden thoughts in which he urges himself to “just say it out loud to see how it feels.” This is pop music as psychotherapy, reminiscent of John Lennon’s primal screaming on the 1970 song “Mother.” West’s autotuned voice seesaws between childish chirp and monstrous baritone, the effect made all the more chilling by the spooky synth whisper his words float on. As he jokes about killing himself, then about killing the song’s unnamed addressee, his delivery is a lazy, spoken-word freestyle, picking up steam only when the beat arrives in the final minute. We’re a world away from the airtight songcraft of West’s peak years, but the audacity is breathtaking: here is a reviled celebrity inviting us into the haunted house of his mind as if we still cared, daring to imply that anything offensive that comes out of his mouth is the side effect of a deep-seated death wish.

Few pop stars can bend social reality with as much shameless narcissism as West has: this was clear in 2013’s “Blood on the Leaves,” which found him spitting a lurid tale of infidelity over a loop of the classic protest song “Strange Fruit.” It’s no surprise, then, that he has answered concern over his alt-right sympathies not with an explanation of his politics but with yet another navel-gaze. Boasts of sexual conquest (“I could have Naomi Campbell / And still might want me a Stormy Daniels,” he raps on “All Mine”) give way to the R&B-infused remorse of “Wouldn’t Leave,” the album’s most detailed reckoning with his recent controversies. On that song, he discloses that his wife, Kim Kardashian, feared his inflammatory remarks about slavery would tarnish their images beyond repair. He claims to have offered to set her free from their marriage, but the chorus intones, “I know you wouldn’t leave,” in a cringe-inducing display of self-assurance that one can only assume West mistakes as romantic.

As a wordsmith of fairly humble gifts, West has never had much to say beyond fuck you, love me, don’t leave me. But his ear as a sound collagist can still stop you in your tracks. And so it happens that, against all odds, ye contains one of his greatest songs, a bittersweet reminder of how beautifully his mind moves between sonic ideas. The guitar-driven “Ghost Town” begins with a dusty gospel sample, blooms with a melancholy hook drawled by Kid Cudi, and features a single Kanye-led verse for good measure. But as he has sometimes done in the past, West yields the floor to anthemic melody and a brash female voice. In the song’s outro, newcomer 070 Shake paints a disturbing picture of self-harm (“I put my hand on a stove / to see if I still bleed”) that leaps out of your speakers, and West does right by her performance, letting it embody his own fears of oblivion. As the vocals burst and dissolve against a backdrop of silence, the tone is almost valedictory, an acknowledgment that even the boldest sounds fade into nothingness.

Andrew Chan is web editor at the Criterion Collection. He is a frequent contributor to Film Comment and has also written for Reverse Shot, Slant, Wax Poetics, and other publications.