Simon Reynolds

Simon Reynolds

Do androids dream of electric guitars? A look at science fiction’s influence on the music of the 1970s.

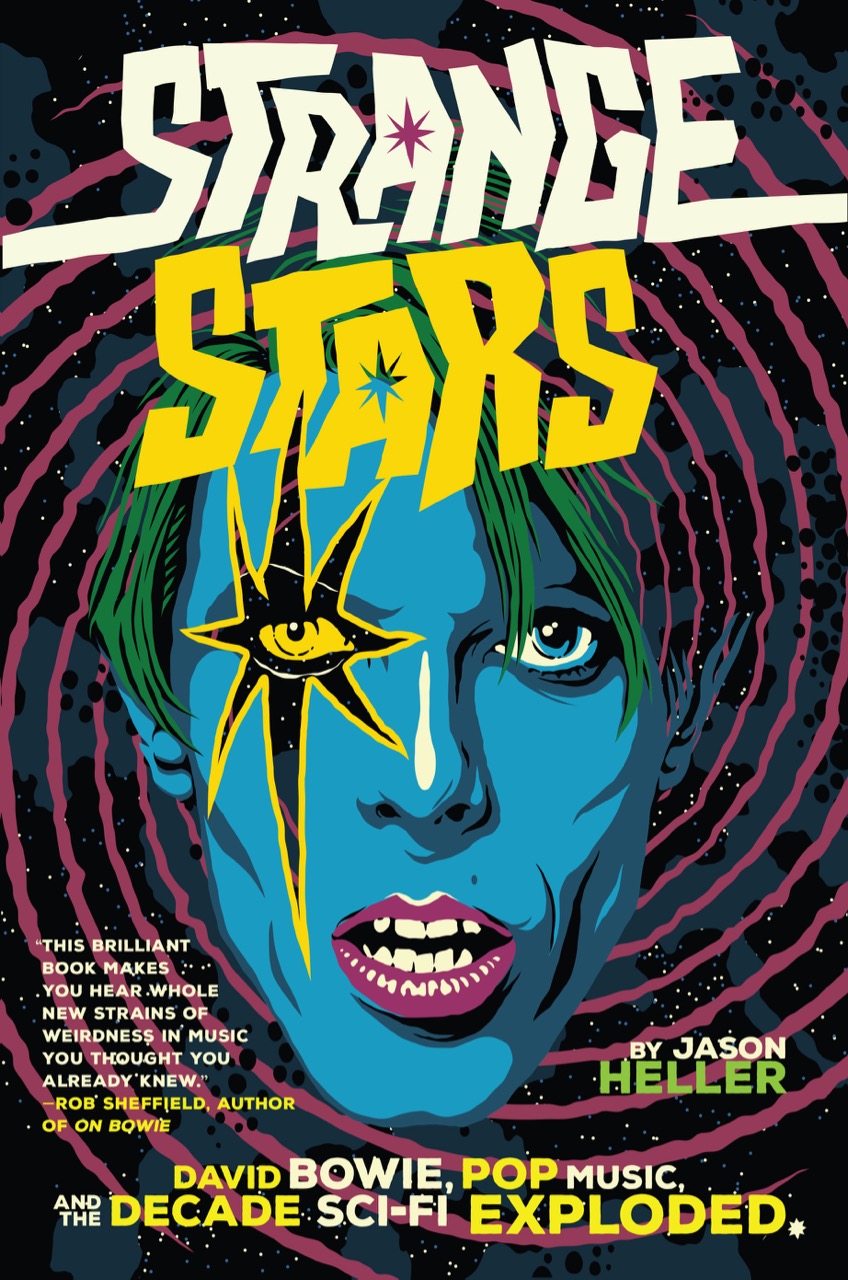

Strange Stars: David Bowie, Pop Music, and the Decade Sci-Fi Exploded, by Jason Heller, Melville House, 254 pages, $26.99

• • •

Strange Stars starts with author Jason Heller recalling a profoundly formative experience: a David Bowie stadium concert in August 1987, when the Glass Spider tour reached his hometown, Denver, Colorado. Not the most auspicious initiation, perhaps: generally deemed a garbled farce of overdone spectacle, Glass Spider might be the nadir of Bowie’s increasingly rudderless eighties. Still, for fifteen-year-old Heller, the sound and vision—“a tornado of catsuits, astronaut costumes, and gold lamé”—blew his mind. The wonderment of that night propelled him along his life-path: a parallel trajectory that entwines being an active musician in various bands and an acclaimed science-fiction writer. (Author of the counterfactual satire Taft 2012, Heller also won a Hugo Award for his contributions to the magazine Clarkesworld.)

Coming at his subject, the interface between popular music and science fiction, from an unusual angle—as a practitioner of both s.f. and music, rather than rock critic or historian—gives Heller a fresh perspective. One fascinating thread concerns the surprising number of direct collaborations between rock bands and s.f. writers. Admittedly, they’ve rarely reached fruition: Theodore Sturgeon, for instance, was invited by Jefferson Airplane’s Paul Kantner and ex-Byrd David Crosby to turn their song “Wooden Ships” into a screenplay, but the process collapsed amid an excess of egos. Heller’s deep familiarity with his genre’s history also enables him to cross-reference the publication of landmark books with songs that appear to have borrowed from them: Bowie’s 1967 song “We Are Hungry Men”—a comic satire about an overpopulated near-future—was recorded suspiciously shortly after the final portion of Harry Harrison’s Make Room! Make Room! was serialized in the UK.

Despite being a musician, Heller’s approach in Strange Stars is largely lyric-based, treating songs as “a vehicle for science fiction.” He quotes from Kodwo Eshun’s More Brilliant Than the Sun but oddly doesn’t make use of the Afrofuturist critic’s concept of “sonic fiction”: the ways in which production, effects, timbres, and other futuristic or spacy audio elements create effects of disorientation and estrangement. Take “Silver Machine” by British cosmic rockers Hawkwind: it’s the sound of the single—Chuck Berry riding a Mercury rocket rather than a Chevy, a vertiginous whoosh into the beyond—that transports the listener, rather than the half-buried lyric about a vessel that “glides sideways through time.” Likewise, Bowie’s Low—devoid of s.f. lyrics—feels more science fiction thanks to its innovative production and brittle, neurotic rhythms than Ziggy Stardust and Diamond Dogs, whose songs about alien messiahs and Orwellian dystopias come clad in relatively conventional rock settings.

Although Bowie’s name is highlighted in the book’s subtitle and he appears often enough to approximate a narrative spine, one can’t help wondering if this slant was intensified after the glam rock visionary’s 2016 death, reframing what was originally intended as a broad survey of the s.f. influence on seventies pop music. But that 1970s emphasis itself also stirs a wrinkle of doubt. For sure, Heller’s list of definitively seventies genres—“Krautrock, glam, heavy metal, funk, disco, post-punk”—all deployed imagery related to the future, space exploration, etc. But pop’s infatuation with s.f. started well before 1970 and continued to flourish into the eighties (the era of synth pop, industrial music, and electro) and nineties (rave culture and techno).

Despite those somewhat arbitrary boundaries, Strange Stars provides a brisk and entertaining tour through terrain that has not been mapped at book length before. The briskness does have a downside. Strange Stars is structured as a year-per-chapter arc through the seventies, which means that the same figures keep cropping up, but often in a glancing way before we hurry on to the next example. Whenever the narrative slows and zooms in, it’s a richer read, as with sections on Hawkwind’s relationship with doyen of the British New Wave s.f. scene Michael Moorcock, Devo’s Spengler-retooled-for-MTV vision of humanity’s degeneration, and Poly Styrene of X-Ray Spex’s lyrical fantasias of consumerism-gone-crazy.

At other times the book can feel like a hectic and overly wide trawl that often pulls in things only tenuously connected to s.f. (a song that references a planet, a robotic dance style briefly in vogue). Midway through, I began to feel that while a formidable accumulation of evidence was underway, the case actually being argued had yet to emerge. Clearly there is a deep connection between rock and science fiction. Both forms operate within an uneasy but potent interzone between lowbrow and lofty, juvenile trash and avant-garde bohemia. But why haven’t other pulp fiction genres—westerns, hardboiled detective stories, mysteries—bonded with rock to anything like the same extent?

As Heller notes, it’s striking that several of the very first magazines containing rock criticism were launched by figures who came out of the s.f. fanzine scene. Later, music papers like NME would regularly profile writers like J.G. Ballard. Science fiction and rock both have an association with youth culture. While some stick with either or both for their whole lives, fanatical involvement is generally associated with adolescence and the early twenties. That super-intense seriousness—seeing s.f. or rock as a world-transformative force, or as a world unto itself—is an overestimation you’re supposed to grow out of.

But why is the affinity between rock and s.f. so strong, and what is the connection with youth? A clue can be found in a Bowie song mentioned in the book largely because of its title: “Life on Mars?” Heller rightly points out that the lyric isn’t really science fiction. But the song scenario and its emotional tenor do evoke exactly the sort of longings and frustrations that fuel “the desire called utopia,” the poetic subtitle of Fredric Jameson’s s.f. study Archaeologies of the Future. Bowie’s own account of “Life on Mars?” is that it’s about “a sensitive young girl’s reaction to the media.” Formulaic entertainment offers no relief (“the film is a saddening bore”), TV news presents a panorama of absurdity (“the workers have struck for fame”), and humanity in all its futile striving seems lemming-like (“the mice in their million hordes”). The question of the title is at once an indictment of the sheer mundanity of life on Earth and a sighing entreaty: there must be more than this, an absolute elsewhere.

Good on the details of s.f.’s interactions with rock, Strange Stars never addresses this deeper commonality: the fact that it’s the insufficiency of the world as is—and the inadequacy of the half-formed adolescent self—that drives kids into the fantasy-systems of science fiction and rock. Both offer ways of being “anywhere but here, anyone but me” through heroic narratives of discovery and danger. The feeling of risk is crucial: indeed, you could twist Jameson’s phrase and talk about “the desire called dystopia.” As shown by the contemporary boom of YA fiction set in totalitarian near-futures, or by the catastrophe sub-genre of sci-fi, it’s even more exhilarating to imagine being tested by extreme predicaments or struggling to survive in a radically (and thrillingly) transformed world. As the novelist John Wyndham—quoted in Strange Stars by Neil Peart, Rush’s drummer and lyricist—once put it, science fiction is about “extraordinary things happening to ordinary people.” That is a large part of rock’s promise too, for fans and for aspiring stars alike.

Simon Reynolds is the author of eight books about pop culture, including Retromania, the postpunk chronicle Rip It Up and Start Again, the techno history Energy Flash, and most recently Shock and Awe: Glam Rock and Its Legacy, from the Seventies to the 21st Century. Born in London, currently resident in Los Angeles, he is a contributor to publications including The Guardian, Pitchfork, and The Wire, and operates a number of blogs centered around the hub Blissblog.