Andrew Chan

Andrew Chan

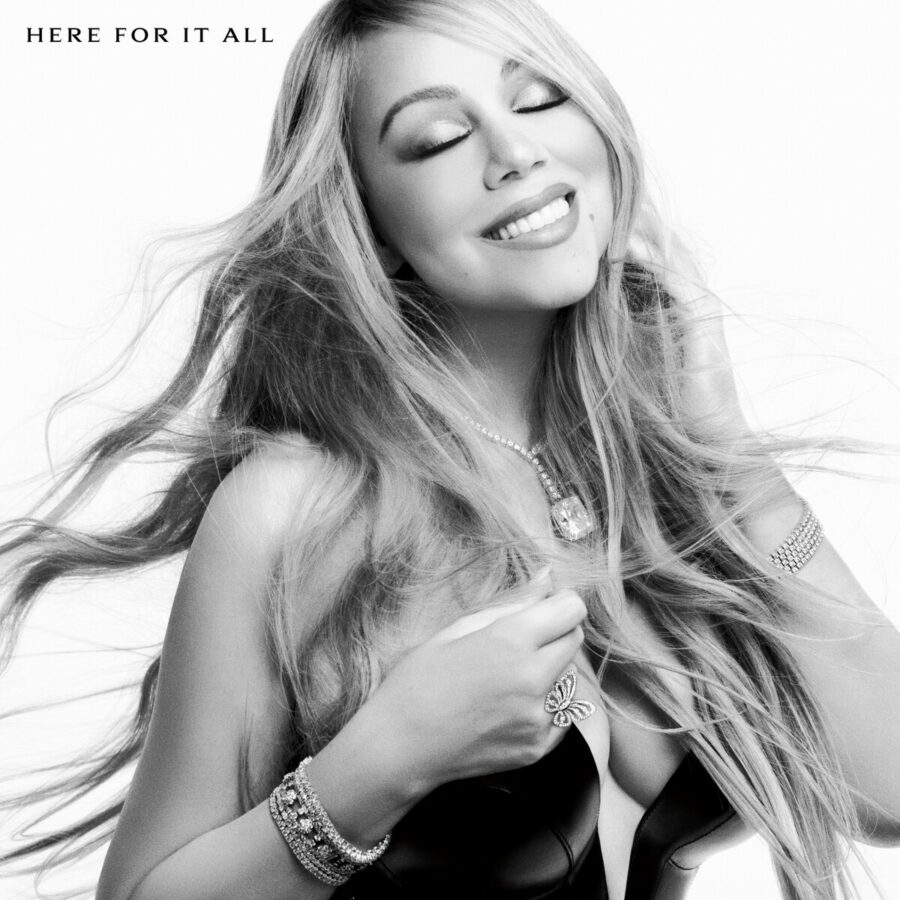

The singer’s sixteenth studio album, Here for It All.

Here for It All, by Mariah Carey, Gamma

• • •

Pop superstars, whose talents are so often eroded by the rigors of fame, don’t tend to produce first-rate music more than a couple decades into their careers. But in the time since her last mega-selling album, 2005’s The Emancipation of Mimi, Mariah Carey has proven herself an exception to this rule: every record she has made in the twilight of her commercial prime contains at least a handful of songs that belong with her very best work. Here for It All, Carey’s sixteenth major release, manages to extend this feat, most forcefully with its astonishing title track.

The culmination of an intimate creative partnership with Daniel Moore II, who became her musical director in 2019, “Here for It All” luxuriates across six and a half minutes and two distinct sections, as if staking out territory for the full scope of Carey’s gifts. Kicking off with churchy block chords that establish an air of funereal solemnity, the song expands, like a great singer’s capacious lungs, to encompass most of her signature gestures: syllabically dense phrasing; a power-ballad octave leap; gutbucket gospel vamping; an oceanic, wall-of-sound vocal arrangement laced with exquisite harmonies and countermelodies. Such profusion calls to mind a feature of Carey’s oeuvre long cherished by hardcore fans (known as “lambs”) but largely unnoticed by casual listeners—the freewheeling, jam-based experimentation found in her epic house remixes of the 1990s, as well as in more recent deep cuts like 2018’s “Giving Me Life” and the sixteen-minute club version of “Portrait” she released last year.

But the shape-shifting structure of “Here for It All” isn’t just a showcase for Carey’s stylistic versatility. As she weaves together contrasting facets of her trademark sound, she is endeavoring another, related act of coalescence. What begins as a declaration of devotion to a loved one (“I lay awake and feel you breathe”) soon morphs into an acknowledgment of emotional agony (“the shakes and withdrawals,” “things I don’t care to recall”) and, finally, an exhortation to “praise the Most High.” Like many R & B titans before her, from Aretha Franklin to Marvin Gaye, Carey regularly juxtaposes the sacred and the secular, but she has never sounded so convinced that the painfully contingent experience of human love is rooted in a divine, abiding agape—or is, as she sings, a “test flight” for it. Part of what makes the song so moving is how her amalgamation of disparate musical elements enacts the lyrics’ attempt to bridge love’s many forms.

“Here for It All” is the richest and most rewarding moment on the album; it’s also the only song that lives up to the spiritual gravitas associated with the soul-diva tradition. The rest of the record is more muted in its impact, which would be fine if a quarter of it weren’t so half-hearted. Where its predecessor, Caution (2018), foregrounded the healthiest parts of Carey’s time-weathered voice and framed them with superb songwriting, Here for It All is less consistent, and its stumbles make it easier to fixate on the singer’s current vocal limitations. As a cowriter, Moore shares the blame for one unconscionable instance: “Nothing Is Impossible,” a dreary ballad that jostles her back and forth between despondency and triumph, then pushes her into some of the feeblest high notes she’s ever attempted to salvage with excessive processing and reverb.

Carey is one of American music’s supreme vocal geniuses, but the difficulties she has faced with her instrument, dating back to the late ’90s, are an open secret that haunts even her most all-forgiving fans. For much of her career, she has been forced to weigh her creative goals against her diminished belting register and coarsening timbre; her evolution as a songwriter with an exceptional ear for sonic pleasure and melodic possibility is one of the few happy results of having to constantly reckon with such erratic conditions. Another silver lining is the way this obstacle has served to humanize her in the eyes of her audience. The drastic transformation of a one-of-a-kind voice is hard to stomach, and the lambs’ drawn-out, album-by-album adjustment to it has been a test of acceptance and grace. For her, these changes have also been a lesson in the art of doing the best you can with what you got—to paraphrase a frequently memeified Mariah locution that encapsulates her defiant attitude toward the high standards she is still asked to meet.

Except for the title track, the best material on Here for It All refrains from chasing the dream of what’s been lost. Instead, these highlights leverage the considerable skill set she still possesses. Her rapper-like instincts for rhythm and cadence are front and center on “Type Dangerous,” a thumping, tongue-twisty mid-tempo track (built on a sample of Eric B. and Rakim’s “Eric B. Is President”) that asserts her centrality to hip-hop history and gets some comic mileage from quintessentially Mariah word choices like “rigamarole” and “yen.” Her flair for evocative pronunciation surfaces in a few faux-patrician line deliveries on the disco whirligig “I Won’t Allow It,” and in the tenderness with which she caresses the plosive consonants in “Here for It All.” And her sensitivity as a duet partner is palpable in “Jesus I Do” (which pairs her with gospel royalty the Clark Sisters) and the gorgeous, rueful “Play This Song,” a collaboration with Anderson .Paak—whose three ’70s soul–influenced contributions mark him as the MVP among the album’s coterie of coproducers.

Strive as I may to appreciate Here for It All on purely musical terms, I’ve followed Carey long enough to know this isn’t possible or even ideal. She is a master interpreter of matters of the heart, animated by her own deeply ingrained contradictions: between the desire for imperious self-sufficiency and the longing for submissive attachment, between surface frivolity and profound introspection. It is no mere indulgence in celebrity gossip to note that the past decade has been a time of upheaval for her: she has suffered from dysfunctional management, begun and ended a few romantic relationships, struggled through deer-in-headlights live performances, parted ways with the imploding major-label system, and mourned the deaths of her mother and sister, who passed on the same day last year.

Though Here for It All is vague about these challenges—“it wasn’t very nice,” she sings at one point, her habitual evasiveness yielding a heartbreaking understatement—the album has the same melancholy atmosphere that pervades the unfairly neglected Me. I Am Mariah . . . The Elusive Chanteuse (2014), which in retrospect reads as a portent of her divorce from TV-personality Nick Cannon. You can detect her discontent in most of these new songs—it’s there in the otherwise bouncy “Mi” (“you couldn’t walk a mile in my shoes”), and in repeated references to her own departure (including the plaintive first line of Paul McCartney and Wings’ “My Love,” which she covers lovingly here: “And when I go away . . .”). In these details, we hear an artist for whom music remains both a refuge from the bitterness of the world and a mirror in which the realities of human imperfection are poignantly revealed.

Andrew Chan is a writer and editor living in Brooklyn, New York. He is the author of Why Mariah Carey Matters, published by University of Texas Press.