Jennifer Krasinski

Jennifer Krasinski

Jamie Lloyd’s new production of Samuel Beckett’s play is in danger of punking a classic most heinously.

Alex Winter as Vladimir and Keanu Reeves as Estragon in Waiting for Godot. Courtesy DKC/O&M. Photo: Andy Henderson.

Waiting for Godot, written by Samuel Beckett, directed by Jamie Lloyd, Hudson Theatre, 141 West Forty-Fourth Street, New York City,

through January 4, 2026

• • •

So ingeniously conceived is director Jamie Lloyd’s production of Samuel Beckett’s Waiting for Godot that the reviews could almost write themselves. One possible title: “Godot’s Excellent Adventure,” or something equally cheap but cheerful. The opening lines: heartfelt kudos for the inspired stroke of casting that not only reunites Keanu Reeves and Alex Winter—beloved stars of Hollywood’s beloved Bill & Ted trilogy—but also allows them to freshly flex their chops. Thereafter would come a report on the dizzying delights of seeing icons on icons on icons—Alex and Keanu and Bill and Ted and Didi and Gogo all on one stage—noting the fusions and confusions, whether literary or existential, between the celebrities and their Gen-X slacker characters and Beckett’s hapless pair. Ah, the semiotic complexities! The seemingly endless meta-texts! Finally, the review would deliver the ready kicker, either rating the production most excellent or encouraging the team to “Try again. Fail again. Fail better.”

But such are the traps laid by cleverly packaged classics like this one, which have earned Lloyd an outsize reputation. They make it easy, even pleasurable, for a critic to stick to the scripts handed them, to delight in every telegraphed ah ha. It’s hard to shake the nagging feeling that beneath the stylish design and dramaturgical “hot take” lurks the bad conscience of a director who brims with ambition but somewhere along the line has confused success with making their mark. Enraged by Lloyd’s Godot? No. Unmoved, disappointed. I’d wanted to revel alongside Reeves and Winter as they had a turn at Gogo and Didi, but instead I just watched them in it. The production’s posters, plastered all around New York, joke that Godot is “The greatest play ever written about nothing.” And while of course it isn’t about nothing, it is never not a marvel how Beckett, in his story of two men waiting for someone who never arrives, distilled the murk and overwhelm of human existence into a strange and gleaming work that freshly detonates the stage even seventy-some years after its debut—who made the whole of our world so vivid, so alien, in a space he invokes with the sparest, most precise stage directions: “A country road. A tree. Evening.”

Keanu Reeves as Estragon and Alex Winter as Vladimir in Waiting for Godot. Courtesy DKC/O&M. Photo: Andy Henderson.

Can a single detail from a production serve as the metaphor for its failure? Let’s find out: in a silly move, Lloyd has axed Beckett’s tree. Cut it from the stage, felled it from view. It’s nowhere in sight. A few minutes in, as Didi (Winter) and Gogo (Reeves) muse on whether it’s a dead willow or a bush, the audience realizes that Lloyd has transplanted it, so to speak, somewhere above their heads, leaving his lead actors in the embarrassing position of pointing and gesturing into the void. Godot’s tree is no small detail; it’s the stage’s only stalwart, at once a mooring and a marker for the passing of time, among its other roles. To make the obvious pun, the show suffers the loss of its limbs. The moment Didi and Gogo contemplate hanging themselves from it felt a little like watching Hamlet bemoan the fate of Yorick without a skull in hand. Alas, poor Beckett. While to tree or not to tree might be a question worth asking, Lloyd’s answer is trite. Perhaps having taken to heart the supposed “nothing” of Godot, he inserts other frivolous absences throughout, at times reducing the complexity of theater to an infantile game of pretend. His choice to have Winter and Reeves awkwardly mime invisible turnips, radishes, and carrots; the decision to chase an obvious laugh by having the duo briefly shred air guitars—all these moves deliver the unfortunate, surely inadvertent, message: we’re not playing for real.

Alex Winter as Vladimir and Keanu Reeves as Estragon in Waiting for Godot. Courtesy DKC/O&M. Photo: Andy Henderson.

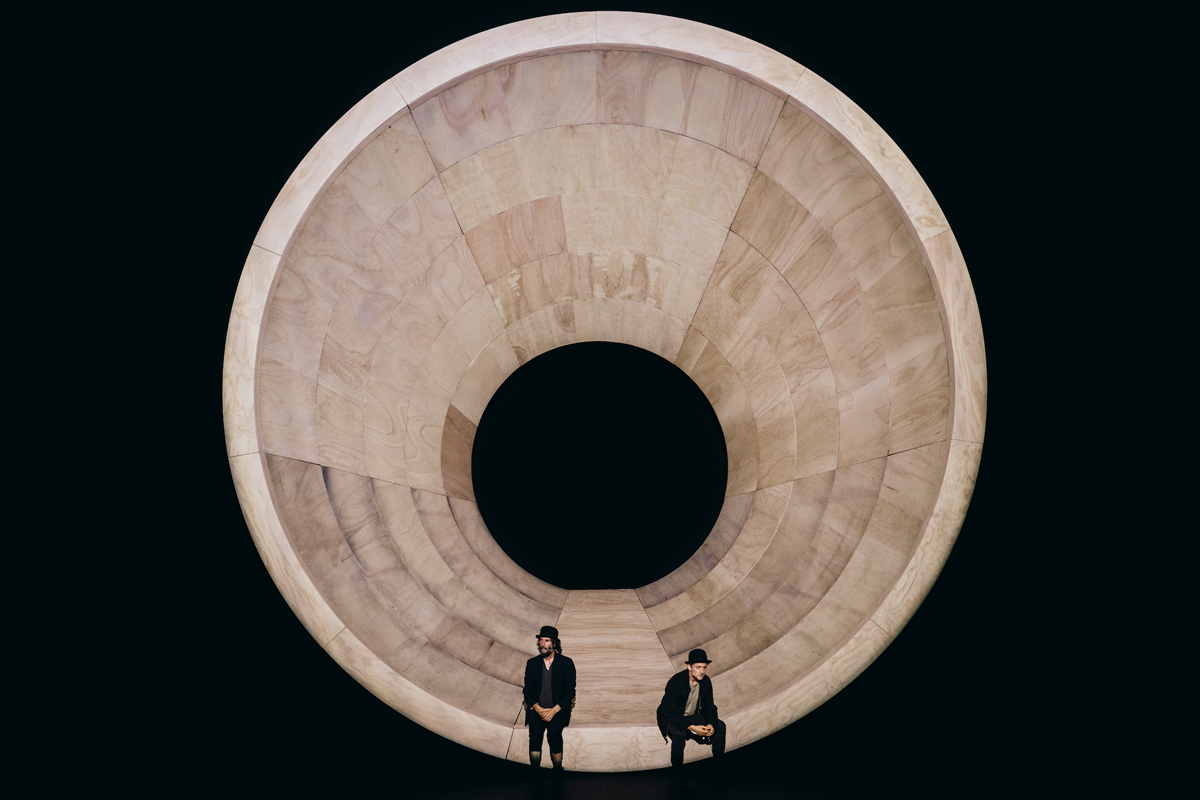

Designer Soutra Gilmour rips the seams even further, swapping Beckett’s country road for a stage-swallowing set piece that looks like something between a concrete pipe and a camera lens. It’s a striking sculptural work to be sure, and together with Jon Clark’s exquisite lighting produces some very chic stage pictures, but it condenses the playing space to such an absurd degree that rather than wrestling and imagining what to do with themselves as their characters wait and wait and wait, the actors largely just sit or stand in place. It doesn’t help matters that when the lights go down, we hear the sound of a camera click. Bless. Somewhere in this production it seems Lloyd has seeded a low-key meditation on theater versus film, or on acting versus celebrity. Although I can’t stoop to excavate it, I will say that hobbling an actor by pointing up the fact of their fame inspires little trust in a director’s intentions.

Alex Winter as Vladimir, Michael Patrick Thornton as Lucky (in wheelchair), Brandon J. Dirden as Pozzo (seated on stage), and Keanu Reeves as Estragon in Waiting for Godot. Courtesy DKC/O&M. Photo: Andy Henderson.

Reeves and Winter are as good as they can be given the needless impositions and interferences; better when their warmth and palpable delight in one another undergirds their characters’ odd yet tender bond; best when the fourth wall is upright, and Beckett’s world advances, and Gogo and Didi are allowed to come to the fore. As Didi, Winter’s eyes glitter, turned ever upward, his head in the clouds. He brims with curiosity while making sure Didi never wears his hope like a fool. Reeves is a shaggy, soft-spoken Gogo, he of ill-fitted boots and weeping wounds and dwindling memory. The actor pulls himself inward; his Gogo is downcast, off-balance, confused, as if he were teetering between here and elsewhere. The duo find formidable foils in Brandon J. Dirden, a thunderous, magnetic Pozzo, and Michael Patrick Thornton, whose deadpan Lucky looks like he might combust at any second.

To be clear, mine is not a bid for purism. But merely punking a classic is never as interesting as rising to the occasion of its genius. American directors like JoAnne Akalaitis, Robert Woodruff, and—most brilliantly—Elizabeth LeCompte and the Wooster Group have modeled ways in which a production can explode a play, expose its many facets, and open it up to the present tense. Such artists also prove that it’s not a strategy for the feint of vision, and that it certainly can’t be done by half. Watching Lloyd’s Godot, I couldn’t help but think that the director might do something more provocative with his own star power and use it to shepherd the new playwrights that the theater so desperately needs right now. What a radical and—fine, I’ll give in—most excellent choice that would be.

Jennifer Krasinski is a writer, critic, and senior editor at Bidoun.