Andrew Chan

Andrew Chan

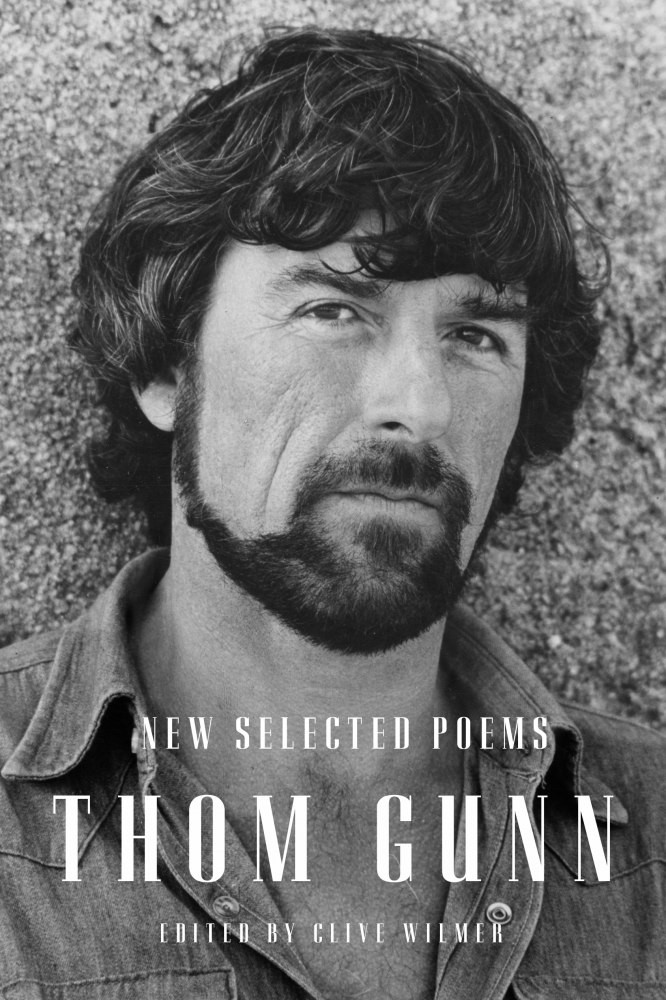

Love, AIDS, and a “firm dry embrace”: a new anthology of

the poet’s work.

New Selected Poems, by Thom Gunn, edited by Clive Wilmer,

Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 284 pages, $30

• • •

Not all subjects are equal. Or at least that’s the conclusion I come to again and again when reading the great English poet Thom Gunn, whose work has been lovingly reanthologized by his friend Clive Wilmer in New Selected Poems. Encountering a sampling from Gunn’s 1992 masterpiece The Man with Night Sweats within the broader context of his career is a shock to the system, no matter how aware the reader is of the mercurial literary life that led up to it. After four decades of moving across admirably eclectic terrain—platonic and erotic intimacy, modern city life, apocalypse, drugs, and the American counterculture—the poet found in the scourge of AIDS a topic that warranted his sustained attention. So fully committed is the book’s lucidity that it recasts all of that earlier writing—even the most gorgeous and deeply felt of it—as one long rehearsal. It’s as if he had been preparing all along for this unforeseeable emergency.

Gay male writers who were alive during the plague had to find ways of documenting all the loss that was hurtling toward them. Their responses varied in style, temperament, and political aggressiveness, from the potent rage of Paul Monette and Larry Kramer to the misty-eyed lyricism of Mark Doty. By and large, the writers most regularly associated with this explosion of gay literature were several years younger than Gunn, who was well into middle age when Night Sweats was published. His elegies for the AIDS dead evince a comfort with what it is to be mortal, and contain none of the grandiosity that can creep into the work of less-experienced artists trying to fasten raw talent to real-world cataclysms. Most poignantly, these poems hint at the discipline required of a generation that came of age in the silence of the closet, a silence enforced by the criminalization of same-sex relations on both sides of the Atlantic. (As Wilmer’s excellent introduction to New Selected Poems notes, it was two decades into his career before Gunn began to write openly about gay experience.)

You can see that discipline at work in the unforgettable opening line of “Lament,” one of Night Sweats’ crown jewels: “Your dying was a difficult enterprise.” Such carefully modulated formality, never allowing itself resolution in a howl of anguish or a clenched fist toward the sky, is emblematic of much of the best writing found throughout Wilmer’s collection, and is particularly devastating when read as the culmination of a lifelong creative practice. As is clear in the diction—the understatement of “difficult,” that astringent noun “enterprise”—Gunn favors a declarative tone stripped of obvious affect, and sometimes paired with a second-person address that further occludes the speaker’s emotions. As if that tone weren’t chastening enough, “Lament” is also hemmed in by a structure of mostly iambic pentameter couplets that march forward with a stiff, almost militaristic determinedness. There’s a paradox embedded in this form: as Gunn’s rhythms enact the tedious work of dying, the poem simultaneously aims to counter that laboriousness with the freedoms afforded by prosodic mastery.

In the heat of crisis, how did Gunn summon such a voice? There are some clues offered in New Selected Poems, which charts the development of his artistry across more than seventy pieces, stretching from his debut in the UK in 1954 to his swan song, Boss Cupid, published four years before his death in San Francisco in 2004. Read from cover to cover, the anthology suggests that to express suffering with such exquisite dispassion, it helps to have been a bit old-fashioned to begin with, and to have undergone a long apprenticeship in those Elizabethan literary ideals that discourage idiosyncratic personae and assertions of individual feeling.

Gunn first won acclaim as a precocious young member of the Movement, a loosely associated collective of writers (including Philip Larkin and Donald Davie) who prized a kind of anti-romantic, distinctly British traditionalism at odds with the modernism of their day. His devotion to what he called the balance of “Rule and Energy” was nurtured by poet Yvor Winters, with whom he studied at Stanford. Gunn’s two volumes from the 1950s—the new collection includes fourteen poems from them—have a mixed legacy: praised upon publication for their self-evident virtuosity, and still fervently admired by some fans, they nevertheless have an awkward, occasionally leaden effortfulness about them, especially when compared to the depths he’d endow these same techniques with decades down the line.

Pet themes emerged in these books: codes of masculine stoicism; existential disquiet; and the allure of biker-boy iconography, famously invoked in one of Gunn’s greatest early poems, “On the Move” (“On motorcycles, up the road, they come: / Small, black, as flies hanging in heat, the Boys”). But even in the presence of these subjects, there’s the sense of a voice so vacuum sealed it can hardly draw breath. In later years, Gunn would clarify this insistence on impersonality by striking a contrast with the confessionalists, specifically Sylvia Plath, whose poetry he found to be “a kind of rambling hysterical monologue.”

And yet, in spite of this emotional conservatism, Gunn had a culturally adventurous, if not a terribly political, streak: his move to America brought him under the influence not only of the free verse of Robert Duncan and Allen Ginsberg but also of hallucinogens. It was his double embrace of love and drugs that began to aerate his style. You can feel this loosening even in the tight couplets of 1970’s “Moly” (“I push my big grey wet snout through the green, / Dreaming the flower I have never seen”), in which the tension between straitjacketing form and deliriously tripped-out subject matter is exploited to breathless effect, and in the delicate little enjambments of 1966’s “Touch” (“my skin slightly / numb with the restraint / of habits, the patina of / self, the black frost /

of outsideness . . .”), one of the most glorious of all modern love poems.

The pleasures of the tangible so transcendently expressed in “Touch” reappear in a more solemn form in another Night Sweats highlight, “The Hug” (also featured in New Selected Poems), which culminates with “The stay of your secure firm dry embrace.” That string of adjectives—hauntingly unpunctuated, and notably lacking that clichéd standby “warm”—tells you all you need to know about Gunn’s grasp of highly charged material. Like his American elder Elizabeth Bishop, with whom he became friends, he was at his most resonant when sticking to the facts of the material world. And so in Night Sweats, the potential for loss is revealed in the weight of flesh on flesh: “The whole strength of your body set, / Or braced, to mine.” It’s not to diminish his extraordinary gifts that I reiterate how much these late poems eclipse his others. In them, death gives his formalism a new, vengeful life, allowing the music of rhyme and meter to operate less as a signifier of aesthetic refinement and more as a desperate shield against grief.

Andrew Chan is web editor at the Criterion Collection. He is a frequent contributor to Film Comment and has also written for Reverse Shot, Slant, Wax Poetics, and other publications.