Noah Chasin

Noah Chasin

The Whitney revisits the art of a brash, problematic decade.

Julian Schnabel, Hope, 1982. Oil and velvet on velvet, 110 × 158 inches. Image courtesy Julian Schnabel and Artists Rights Society, New York.

Fast Forward: Painting from the 1980s, the Whitney Museum of American Art, 99 Gansevoort Street, New York City, through May 14, 2017

• • •

It was sometime during my fourth or fifth repeated playing of Government Issue’s 1984 LP Joyride—an album that I gravitated to in the days following November 8—when I realized my revisiting of eighties hardcore punk was not mere coincidence but instead an unconsciously selected soundtrack for my newly enraged soul. Since that revelation, I’ve found it hard to parse any endeavor from anywhere outside the frame of our roiling geopolitical landscape, and have attempted largely in vain to find solace and contemplation in other immersive activities.

Hardcore punk was born of the same frustrations as the struggles against sexual, racial, and economic discrimination. The 1980s was a difficult decade for the US, with the rise of Reagan, of neoliberalism, the demonization of urban heterogeneity, and, important in this context, the first stirrings of contemporary art’s importance as an asset: a class-based determination of status that now confers its luster on the likes of Jared Kushner and Ivanka Trump.

My awareness of the 1980s art scene came slowly and somewhat belatedly in the decade, with Jean-Michel Basquiat’s high-profile overdose in 1988, the AIDS crisis and its devastating effect on the art world, and the ascendance of Julian Schnabel to tabloid fodder. It seemed to me a time during which artistic acclaim followed a very different trajectory than it had in the past: bombast and narcissism, buoyed by a surfeit of drugs and money, created larger-than-life luminaries who, in turn, fabricated larger-than-life paintings that sought to vie with the confident, large-scale, academic works of seventeenth- and eighteenth-century Europe.

For reasons that likely have as much to do with the predictable cycling through the recent past as they do with finding renewed relevance in works being displayed in contemporary political and cultural contexts, the past decade has seen a spate of 1980s-themed exhibitions, including Douglas Eklund’s The Pictures Generation, 1974–1984 (2009), David Salle and Richard Phillips’s Your History Is Not Our History (2010), and Helen Molesworth’s This Will Have Been: Art, Love & Politics in the 1980s (2012). The Whitney’s new exhibition, Fast Forward: Paintings from the 1980s, organized by Jane Panetta with Melinda Lang, focuses solely on painting’s resurgence while deliberately minimizing the era’s key political crises. All the works come from the museum’s own collection, and several were acquired specifically for the current show. Some of the included artists also participated as curatorial consultants.

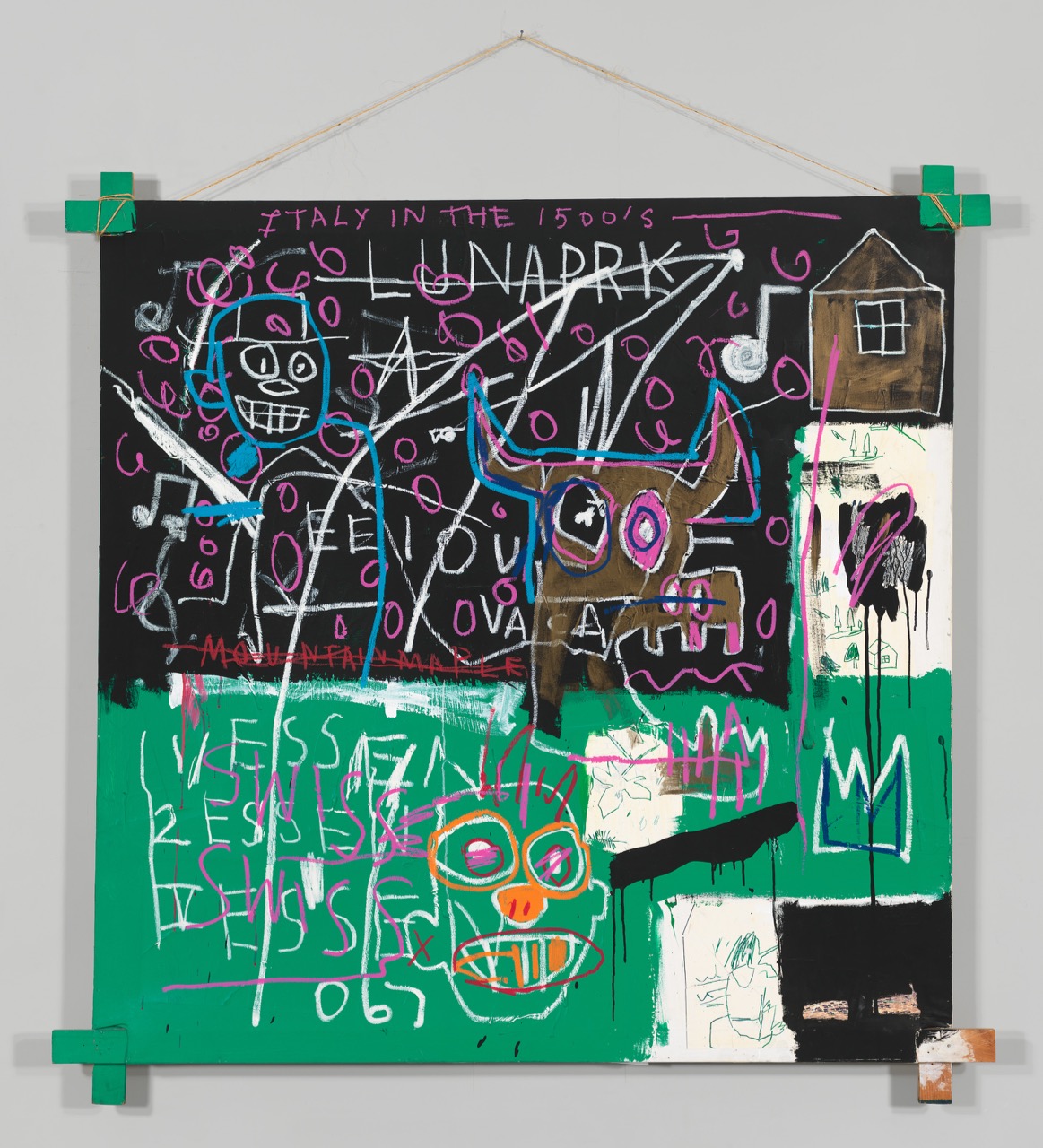

Jean‑Michel Basquiat, “LNAPRK”, 1982. Acrylic, oil, oil stick, and marker on found paper on canvas and wood, with rope, 72 1/4 × 66 5/16 inches. Image courtesy the Estate of Jean-Michel Basquiat, ADAGP, Paris, and Artists Rights Society, New York.

I confess to finding much of the NYC-based 1980s painting—neo-expressionist, postmodern, neo-geo—compelling and seductive from a purely formal point of view. I will never tire of the restless faux-illiteracy on display in Basquiat’s large 1982 work “LNAPRK”, with its grimacing death heads, crudely drawn house, and scatter of pink circles failing to obscure inscriptions of musical notes, inscrutable letters, and scribbled numbers. Leon Golub’s White Squad I (1982), a massive 120 by 210 inch leviathan of acrylic on linen, reminds us of the sheer physicality of Golub’s painterly method, its abraded surface depicting menacing, armed figures culled from photos of Latin American death squads. Quieter, but no less argumentative, is Mary Heilmann’s Big Bill (1987), a work that resembles a standoff between Barnett Newman and Yves Klein: push-pull cadmium blue corners battle for primacy with a white lightning bolt splintering its middle.

These large-scale compositions effectively channeled the brashness of the age, the refusal of artists to be constrained by scale or material, the sheer excess of paint itself a rebuke to austerity and a celebration of overindulgence. Elsewhere in the surprisingly modest-sized show, an assembly of smaller works by David Wojnarowicz, Glenn Ligon, and Ida Applebroog (among others) is hung salon-style on a single wall. This represents a timid attempt to recreate what the curators claim was the bristly, ad hoc installation style of such legendary exhibitions as Collaborative Project’s Times Square Show, a DIY effort from June 1980 that brought together works by many now-recognizable names (Nan Goldin, Kiki Smith, Basquiat, Jenny Holzer, Fab 5 Freddy) in a building that formerly housed a massage parlor on Forty-First Street and Seventh Avenue. The Whitney’s montage contains the exhibition’s most politically activated works, and their marginalization through minimization seems to be an outgrowth of the exhibition’s larger mandate, which is to avoid partisan debate and instead investigate the enchantment of the painterly medium. With this decision I take no umbrage—as I said above, the opportunities for escape are few and far between, and though museums play a critical role in the construction of history, they also may be some of the few sites of refuge left as the walls come crashing down (or get built up, if you will). Nonetheless, the exhibition’s emphasis on less political, more easily commodifiable works resonates uneasily both with debates active during the eighties and with art collecting today as a form of trophy hunting practiced by the upper echelons of the one percent.

Terry Winters, Good Government, 1984. Oil on linen, 101 1/4 × 136 1/4 inches. Image courtesy Terry Winters.

Near the end of my visit, my attention alighted abruptly on a wall label that read: “Purchase with funds from The Mnuchin Foundation . . .” The painting before me was Terry Winters’s Good Government, an array of beige, biomorphic forms executed in 1984 with what I can only imagine was the benign intention of paying homage to Lorenzetti’s famous fresco in Siena of the same name. But it was the Mnuchin name that jerked me out of the (art) historical and into the present, referring as it does to Steven Mnuchin, whose OneWest Bank profited lavishly off the victims of predatory lending and subsequent home foreclosures, and who is a former Whitney board member. More poignantly, at this exact moment in time, he is the president’s contentious nominee for secretary of the US Treasury. I’ll just let that big old heap of irony sit with you for a while.

Lorenzetti fell to the side and my aesthetic pleasure was momentarily blunted. At the press opening, the Whitney’s director, Adam Weinberg, had genially reminded the gathered journalists that “art is truly about engagement,” though his words didn’t really resonate as anything other than a cautious stating of the obvious. After my Winters encounter, however, Weinberg’s rules of engagement took on unanticipated meaning, and the Government Issue track “Hall of Fame” floated into my mind. Here are the acerbic lyrics in their entirety: “It doesn’t take that much/When it all goes to your head/Hall of fame/Being on top of it all/Thinking that you’ve made it now.” This being hardcore, the song is by necessity fewer than ninety seconds long—more than enough time to remind us of the still-raw collision (collusion?) between politics, economics, and art.

Noah Chasin writes on the intersection of human rights and the built environment in the age of twenty-first-century urbanization. He teaches at Columbia University, where he is affiliated faculty at the Institute for the Study of Human Rights, and at the New School. He is executive editor at the Drawing Center.