Tobi Haslett

Tobi Haslett

Raoul Peck’s documentary gives James Baldwin a new political mission.

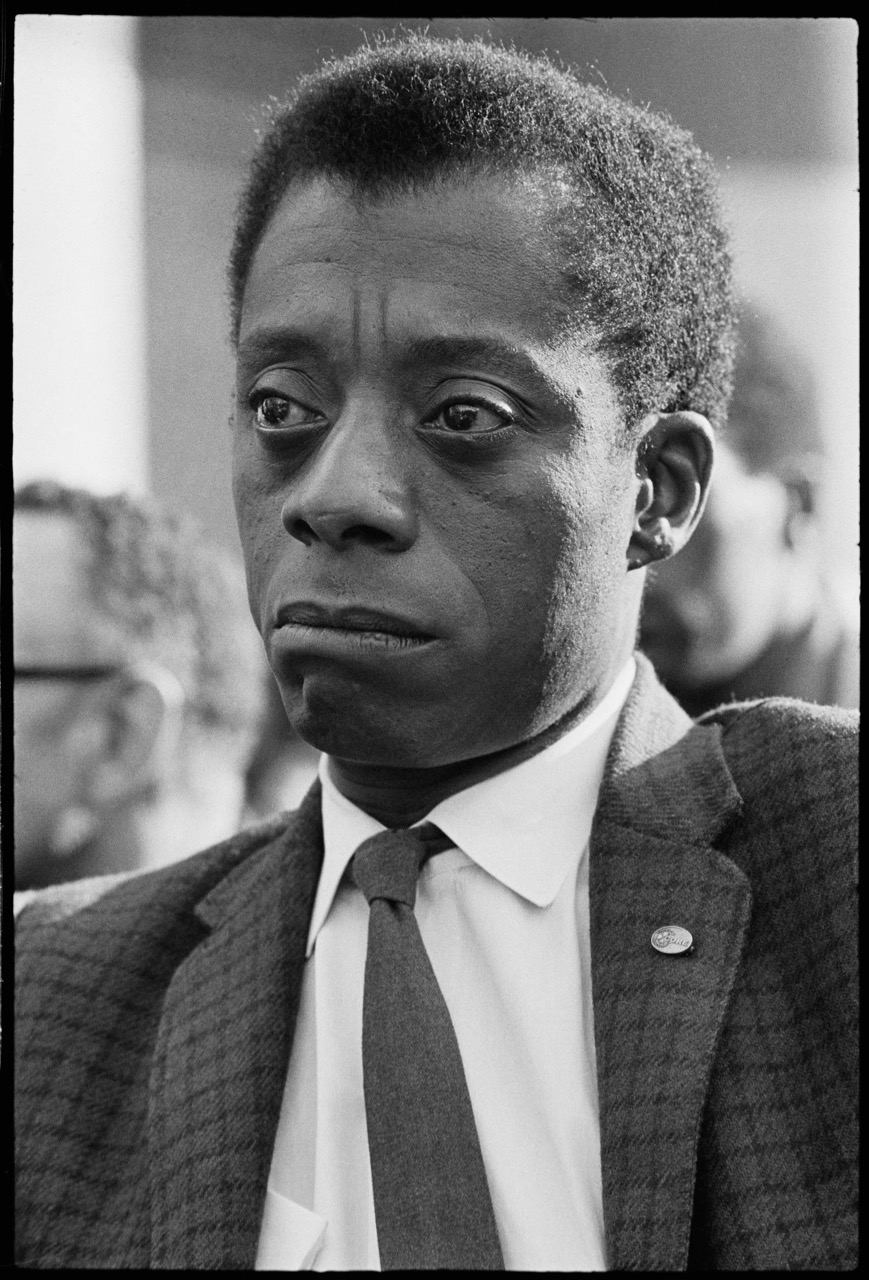

James Baldwin in I Am Not Your Negro. Image courtesy Magnolia Pictures. Photo: Dan Budnik.

I Am Not Your Negro, directed by Raoul Peck

• • •

At James Baldwin’s funeral in 1987, the poet Amiri Baraka took the pulpit and began filling the Cathedral of St. John the Divine with a taut, shouted eulogy that shredded the lugubrious etiquette of the occasion. Grief leapt to frenzy, frenzy flowered into joy—and that joy stirred the assembled mourners to ecstatic applause as Baraka arrived at his furious rhetorical release: “Jimmy was God’s black revolutionary mouth!”

It was a strange thing to say. For all the majesty of Baldwin’s prose—his ear for passion and climax—he was never a spokesman. For much of his life he floated above the clannishness of black politics and pledged a strict allegiance to his own idiosyncrasies: his sexual appetites, his personal tastes, and a prose style that reveled in florid adornments while brandishing its moral force. And in an era of bitter dichotomies and roaring exhortations, he was known for his refusal to choose: between Bessie Smith and Henry James, between Dr. King and Malcolm X, between the political attitudes of black America and the white majority to which those attitudes were the fierce, wounded, ingenious, logical, brilliant reply.

But Baraka was right, in a way—Baldwin was revolutionary—and yes, it had something to do with his black mouth, and the voice that shot from it. He talked like he wrote: with a philosophical seriousness ventilated by wit. The wit lived in the texture, the Barthesian “grain,” of the voice itself. Watch one of Baldwin’s many television interviews and you’ll notice the thrilling oddity of his elocution, how it seems to relish its own vibrations and trills. Sound strains and rattles against the body that produces it, a timbre sensuously attentive to language’s treacheries and subtexts. His speech could be somber, darkly reflective, dragged down by the terrible weight of History—but then it would erupt into brisk, clipped syllables, an adamantine articulation that cuts through the gloom. He had the kind of voice that could, with a flick in tone, sweep away the clutter of our preconceptions: he was a black orator, yes, in the grand ecclesiastical style, but also tart, foppish, lushly vulnerable. He could be haughty—but his hauteur was just. And he always seemed to possess a grimacing awareness of the dissonance he presented, this “former Harlem boy”—as F.W. Dupee called him in the first issue of The New York Review of Books—who had somehow managed to write “the ideal prose of an ideal literary community, some aristocratic France of one’s dreams.” Being black, he was forced to stage a perpetual insurrection against everyone’s idea of him; and, being black, he was often punished for it. Eldridge Cleaver called him a traitor. And William F. Buckley, in the middle of their debate at Cambridge, accused him of affecting a British accent—a jab at the irony, the scandalous dignity, of that voice.

James Baldwin in I Am Not Your Negro. Image courtesy Magnolia Pictures. Photo: Bob Adelman.

Curious, then, that in Raoul Peck’s new documentary, I Am Not Your Negro, which takes Baldwin as its central figure, the voice that narrates the film—that reads Baldwin’s words aloud—belongs to the dull, gruff Samuel L. Jackson. The film itself is largely an embellishment on an unpublished Baldwin manuscript from 1979, Remember This House. It was supposed to be a nonfiction work about the assassinations of Medgar Evers, Martin Luther King, Jr., and Malcolm X, but Baldwin never got past the first thirty pages, overcome by the pain of the task. What we have, then, is his attempt: a sharp gesture that flies back into the preceding decade and illuminates its tensions and wobbling alliances. Jackson is given the honor of reciting the Great Man’s abandoned fragment (as well as a few excerpts from other Baldwin texts, like The Fire Next Time and The Devil Finds Work). Poignant 1960s footage of Harlem and civil rights marches jostle alongside a newer set of pictures: the digitized hellishness of recent anti-police demonstrations and the scenes of slaughter that give them their purpose and desperate, humiliated power. Peck’s project is bracingly simple; as an idea, it’s unimpeachable, somehow indifferent to the details of its execution. Gorgeous text spoken over gripping images, jamming the past into the present to clarify an impending reality that seems both baffling and inevitable, traumatically perplexing and terribly clear. The film has been nominated for an Academy Award.

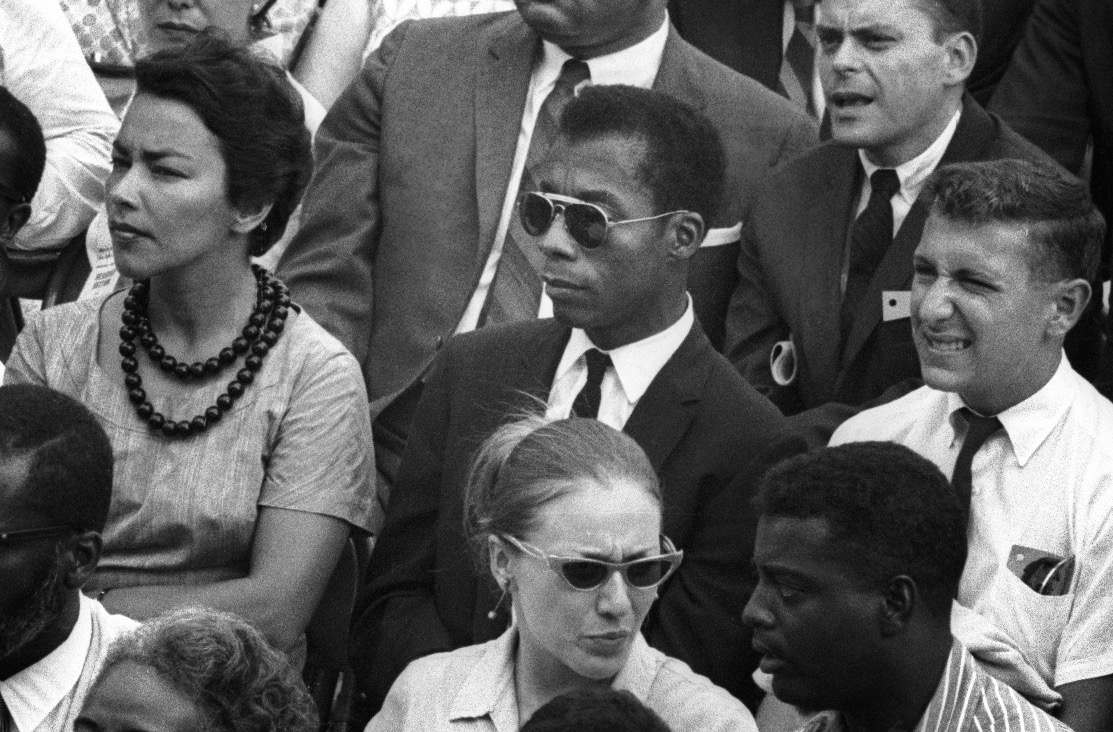

Crowd gathering at the Lincoln Memorial for the March on Washington in I Am Not Your Negro. Image courtesy Magnolia Pictures.

That Jackson should ventriloquize Baldwin is telling; Peck’s choice performs a kind of inkblot test. It reveals what we think, or have come to think, about Baldwin, and what use we have for him. These days he’s been enshrined as a black saint, someone whose feline flirtation with the public sphere, whose elaborate agitation at the demands and gratifications of white readers and viewers, have been displaced by a cleaner, more seemly Baldwin, a more steadfast credit to his kind.

Hence Jackson. There is nothing agitated or mercurial or lyrically jarring in his voice. (There never has been.) It has a ponderous masculinity, full of the kind of low, throaty roll that is sometimes referred to as “rich.” Here, though, that richness seems like a laborious affectation: Jackson, a Hollywood actor trained in the exaggerated techniques of his trade, speaks in a kind of burly stage whisper, never tweaking the tempo or volume of his script. It’s a dramatic, overcompensating way of signaling “interiority.” All the stylistic flourishes of Baldwin’s prose, the jaunty dialectics and coruscating argumentation, are drowned in Jackson’s humorlessness.

Somehow this doesn’t ruin the film; rather it bestows an aching awkwardness that almost seems like a self-reflexive display. The ill-fitting voice tries to snatch Baldwin up from the mythic past, to conscript him to a contemporary political mission, one from which intellectuals of his caliber and manner have been basically excised. Peck dreams of adapting Baldwin to our era (Peck is not, of course, the first) and in doing so has dramatized his own yearning for totems and monuments, his wish to really claim Baldwin for now and for us. It strikes me that in a moment so cracked and discolored by collective horror, these kinds of aesthetic adjustments might be imperative. And I wonder if I hear, in this sanded-down Baldwin, this flattened Jimmy, the lurch and dutiful thump of a new—and needed—political discipline.

Tobi Haslett was born in New York. He has written about art, film, and literature for n+1, The New Yorker, Artforum, The Village Voice, and elsewhere. He is currently a doctoral student in English at Yale.