Noah Chasin

Noah Chasin

Big buildings, big art: three veteran avant-gardists help open the Shed.

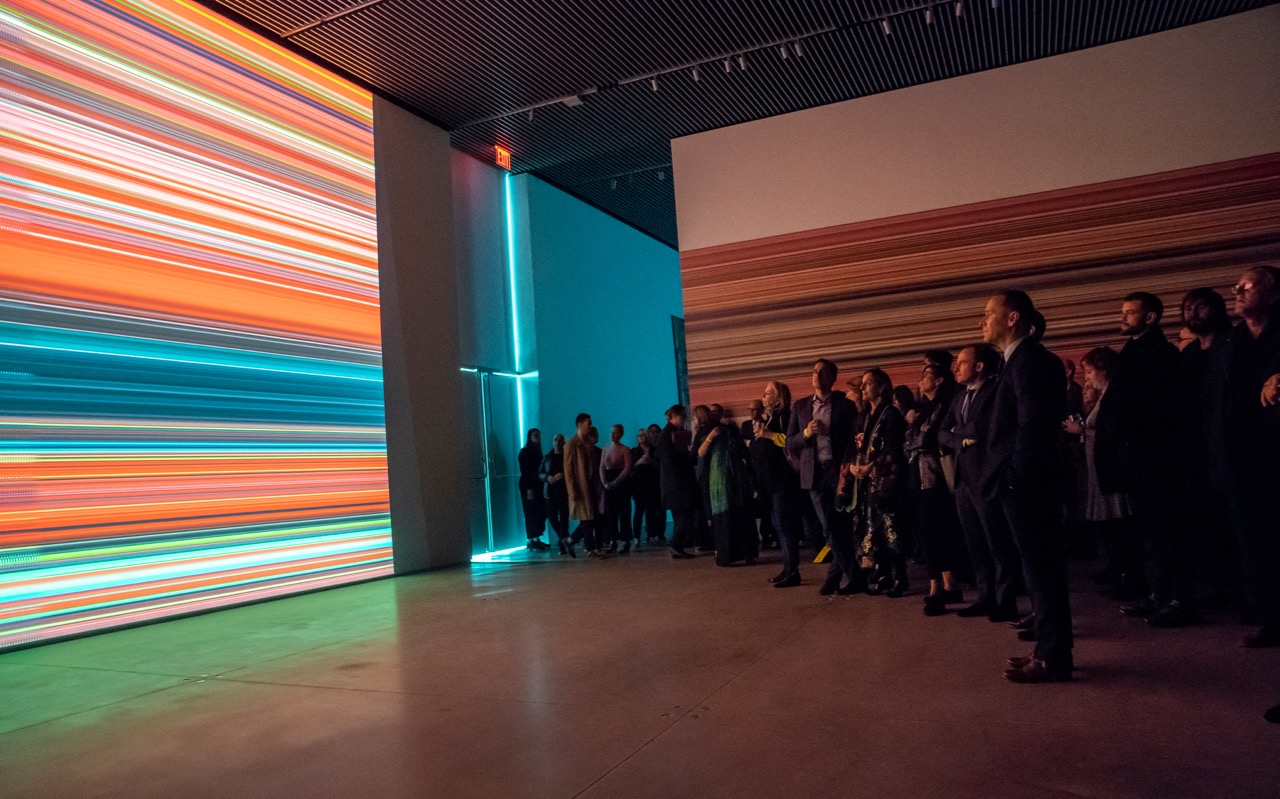

Reich Richter Pärt, installation view. Reich Richter music composed by Steve Reich; moving picture, in collaboration with Corinna Belz, and images © Gerhard Richter 2019. Image courtesy the Shed. Photo: Stephanie Berger.

Reich Richter Pärt, the Shed, 545 West Thirtieth Street, New York City, through June 2, 2019

• • •

The Shed sits hard by the southern edge of Hudson Yards. The Thirtieth Street entrance requires some serious navigation from the subway, and the entrance from the main plaza—facing Thomas Heatherwick’s Vessel (a widely derided architectural folly in the form of a conical staircase)—can be reached only by trespassing across a manicured gravel garden. Dan Doctoroff, NYC’s former deputy mayor and the political instigator of the entire Hudson Yards development, allegedly insisted upon a sui generis building on the site dedicated to ensuring the city’s preeminence as the capital of the global avant-garde. Said structure was delivered by Diller Scofidio + Renfro, reliable representatives of the avant-garde who top many shortlists for prestigious and international commissions. Their multiuse space emerges from a bracketed steel aperture at the foundation of a high-rise residential tower (also of the firm’s design), and comprises several performance venues, rehearsal studios, and exhibition galleries, not to mention excellent views out onto the main plaza.

My rush to witness the Shed’s inaugural commission by composers Steve Reich and Arvo Pärt and visual artist Gerhard Richter left me frustratedly ambivalent. Alex Poots, artistic director and CEO, has teamed with the Shed’s senior program adviser, the ubiquitous Hans Ulrich Obrist, to conjure a trinity that is Too Big to Fail. On one hand, it’s a canny move: all three artists have produced work that has withstood decades of critical scrutiny to emerge as among the most emulated and influential in their fields. Their creations are consistent, lapidary, and masterful. On the other, nothing displayed or performed here is either challenging or paradigm defying. No shots fired across the bow. No edge-of-your-seat astonishment. No hair-raising dissonance. No teeth.

Reich Richter Pärt, installation view. Images © Gerhard Richter 2019. Image courtesy the Shed. Photo: Stephanie Berger.

Richter, the mighty German painter, is the group’s elder statesman at eighty-seven years old. His contributions serve as the foil to the musical cloaks of his two collaborators. Reich Richter Pärt begins in a large room hung with what the curators call “wallpapers” and “jacquard tapestries” designed by Richter. Frankly, they are a bit of an oddly heimisch riff on the artist’s own abstract paintings, producing something that veers uncomfortably close to kitsch (and not in the sharply critical way that some of his earlier, intentionally banal figurative works flirt with the soft pathos of nostalgia).

Though both wallpaper and tapestries have domestic connotations, it’s hard to imagine in whose home these pieces might hang—perhaps the Malibu aerie of a VC billionaire easing into early retirement. As the audience mills about and gazes at the walls, a chorus dressed in street clothes materializes around the room’s periphery and begins to sing. (On the day I attended, the Choir of Trinity Wall Street performed; they alternate with the Brooklyn Youth Chorus for the entirety of the show’s run.) Drei hirtenkinder aus Fátima (2014) was written by Pärt, the Estonian liturgical composer, age eighty-three. The piece, based on an apparition of the Virgin Mary as witnessed by the titular three shepherd children, was first performed amid a Richter exhibition in Basel and is dedicated to the painter. Though Richter and Pärt had long admired each other, this was their first collaboration. This NYC performance reprises that collaboration. Pärt deploys his trademark tintinnabuli (bell-like) method in this amiable a cappella choral piece. Both pleasant and melodious, his plangent composition draws equally from medieval plainsong and the soothing progressions of minimalist sequencing. It’s clear why he is the world’s most frequently performed living composer—his pieces deliver gravitas through an exceedingly accessible musical dialect, the somber “allelujah” choruses marked by euphony and civility.

Reich Richter Pärt, installation view. Reich Richter music composed by Steve Reich; moving picture, in collaboration with Corinna Belz, and images © Gerhard Richter 2019. Image courtesy the Shed. Photo: Stephanie Berger.

Once the singing has finished, ushers gently guide the audience to an adjacent room. At one end sits a fourteen-musician ensemble. The ushers inform us that a film will appear on the wall opposite the musicians. Two extremely long wooden benches flank the room’s lateral sides. Most people move quickly to score a seat, but the pro tip is to wait until the staff brings out the folding chairs—grab one of those and position yourself in the middle of the room.

The lights dim and the music starts. The ensemble strikes up a new composition by the American Reich (at age eighty-two, the group’s sprightly wunderkind). Reich’s work was inspired by a film that Richter made in collaboration with Corinna Belz (the painter’s own documentarian), which in turn follows the logic of Richter’s 2012 book entitled Patterns, wherein the artist subjected one of his abstract paintings to a digital algorithm that divided it into halves, fourths, all the way up to 4,096ths. The film replicates this process: tight horizontal bands of color slowly start to modify, pixelate, and multiply into ever more complex shapes. Reich’s rhythmic minimalism interprets the shifting abstract landscape, the conductor (Brad Lubman of Ensemble Signal, on the day I saw it) driving the music forward while consulting a digital tablet on his podium that runs the film along with timing cues.

Reich Richter Pärt, installation view. Ensemble Signal and conductor Brad Lubman perform Reich Richter by Steve Reich. Photo: Stephanie Berger. Image courtesy the Shed.

Richter’s film is hypnotic—a highbrow Rorschach test yielding apparitions of glass vases, voodoo dolls, and smiling cartoon mouths. Reich’s music is soothing, his trademark mallet percussion anchoring the propulsive and insistent tempo of woodwinds and strings. This is the more successful and enjoyable of the two collaborations, an agreeable and warmly familiar buzz like a dram of a good single malt on a rainy evening.

One can hardly question the wisdom of Poots & Co. for conscripting Reich, Richter, and Pärt into their opening salvo. These artists are prime clickbait for anyone with a passing interest in advanced aesthetics; their collective stature provides enough name recognition to tempt both the older habitués of weekend matinees and the zombies of the hipsterpocalypse alike. How do RRP manage to do it? These three are evidence of how to succeed without losing your street cred. Each is a titan in his own field—prosperous both financially and by reputation—yet each has effectively repelled the unpleasant odor of “selling out” to maintain his avant-garde status. It’s quite a feat, actually, with few analogues in any other creative field. So why is the result ultimately somewhat unsatisfying?

The Shed’s upcoming programming, to be fair, looks very promising in terms of its diversity of genres, ethnicities, and levels of artistic and political engagement. This introductory commission, however, emphasizes some unfortunate truths about the Western canon: that it tends to be composed of aging white men and to cast aesthetics in escapist terms. Reich Richter Pärt seems to envision a zone in which the complicated ambitions of artistic struggle—intellect and emotion, humor and loutishness, succor and conflict—are held at bay, offering asylum from the shitstorm of life as we know it in 2019. The venue’s own folksy name, in fact, suggests it to be a refuge from our fractious political times. But is that really what we want (or need) from our art these days?

Noah Chasin writes on the intersection of human rights and the built environment in twenty-first-century urbanization. He teaches the history and theory of urban design at Columbia University’s GSAPP, where he is also affiliated faculty at the Institute for the Study of Human Rights. He is executive editor at the Drawing Center.