Aruna D’Souza

Aruna D’Souza

Self, society, tear gas: the museum surveys current American art.

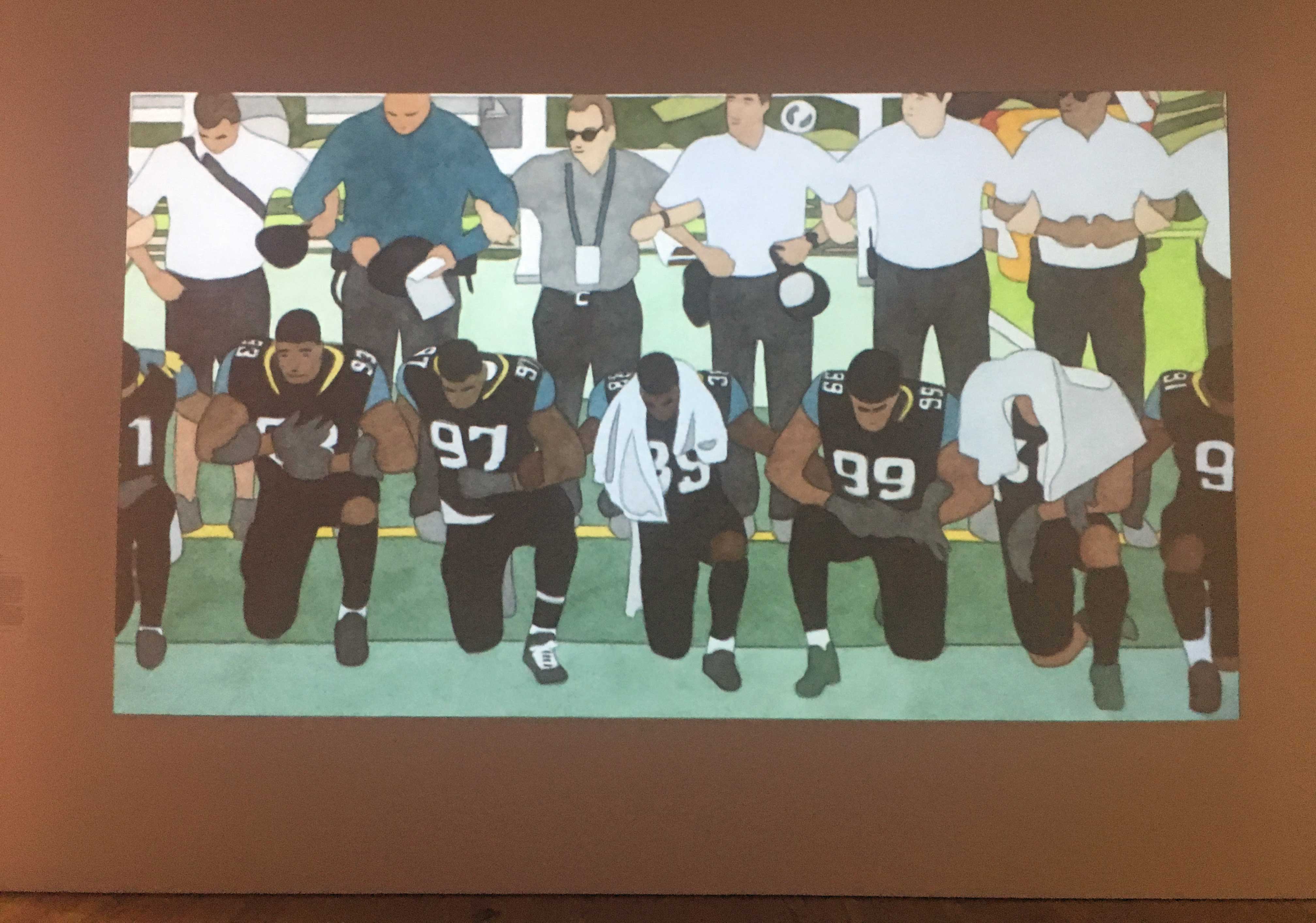

Whitney Biennial 2019, installation view. Photo: 4Columns. Pictured: Kota Ezawa, National Anthem, 2018.

Whitney Biennial 2019, Whitney Museum of American Art,

99 Gansevoort Street, New York City, through September 22, 2019

• • •

Rujeko Hockley and Jane Panetta, organizers of the 2019 Whitney Biennial, got a lot right in a show whose near-impossible brief is to provide a through-line view of the capacious US art scene: there are fewer duds than usual and more shining moments. The roster skews young—nearly three-quarters of the artists are under forty, and twenty-four of those are younger than Jesus—and, for the first time, includes a majority of artists who are not white. Fully half of the participants use she/her pronouns. Artists from Puerto Rico, Indigenous artists, artists with disabilities, trans and genderqueer artists, gay and lesbian artists, Black and Latinx artists, Asian American artists: all are to be found in the list of participants. Much will be made of such demographic facts, but to me they say less about “diversity and inclusion” than about the curators’ refusal of affirmative action for mediocre white men, a policy that has seemed to guide so much museum programming everywhere and forever. For anyone who has been paying attention, Hockley and Panetta have assembled some of the hottest young artists working now, period.

Whitney Biennial 2019, installation view. Photo: 4Columns. Pictured: Tomashi Jackson, Hometown Buffet—Two Blues (Limited Value Exercise), 2019.

In the opening statement for the exhibition, the curators write of their visits to artists’ studios around the country and their ultimate selection of participants: “While we often encountered heightened emotions, they were directed toward thoughtful and productive experimentation, the re-envisioning of self and society, and political and aesthetic strategies for survival.” The statement reads to me as both prescient and anxious—as if they expected audiences might mistake the formal and conceptual depth of the pieces for an absence of real and impassioned politics. Certainly, some of the early reviews, including Linda Yablonsky’s in the Art Newspaper that claims the biennial “is missing a radical spirit,” along with a lot of Twitter chatter coming across my feed that pegs the exhibition as “too elegant” and “too polite,” demonstrate that Hockley and Panetta’s worry was not misplaced.

Whitney Biennial 2019, installation view. Photo: 4Columns. Pictured (foreground): Iman Issa, Heritage Studies series, 2016–19.

The show is by turns beautiful, elegant, formally complex, and even funny at times. It is also fierce. Tomashi Jackson’s chromatically lush and materially complex contributions, including Hometown Buffet—Two Blues (Limited Value Exercise) (2019), are a case in point. Collaged out of paper shopping bags, blue packing tape, fabric, mylar strips, and other materials, sewn together with yarn, adorned with campaign buttons, and overprinted with images and text from newspapers, the piece uses the perceptual tricks offered by Joseph Albers’s color theory, taught to generations of American art students, to bring two histories into alignment: the destruction of Seneca Village, a black settlement in Manhattan razed to make way for Central Park, and the city’s ongoing Third Party Transfer Program, whereby the De Blasio administration has recently been seizing property from black and brown homeowners in gentrifying areas and transferring it to developers in the name of “neighborhood revitalization.” Kota Ezawa’s video National Anthem (2018) is shot from delicate watercolors depicting the Colin Kaepernick–inspired protests of NFL players kneeling during the national anthem before games. By rendering these images in paint, allowing the camera to linger on them, and projecting them on a massive wall, Ezawa removes them from the unthinking speed of social media outrage and lets us dwell on the implications of the action and the reverence of the gesture. Iman Issa’s four Heritage Studies (dating from 2016 to 2019) recreate ancient Syrian, Safavid, Assyrian, and Arab artifacts found in archaeology and ethnography museums around the world as sleek modernist forms, reminding us that the ancient cultures we so admire are the same ones the US government takes military actions against today.

Whitney Biennial 2019, installation view. Photo: 4Columns. Pictured: Daniel Lind-Ramos, Centinelas (Sentinels), 2013.

While the roster of participating artists is fairly unimpeachable (though it is heavy on New Yorkers and the Yale MFA program), the installation falters at times, occasionally in ways that serve to flatten or undermine the political urgency of the work on view. This is especially true of Jackson’s assemblages, which appear in a gallery alongside the delicate, even wan sculptures of Olga Balema, composed of materials like pale tulle and latex stretched over steel armatures and other scavenged stuff. The juxtaposition was based, I would guess, on a desire to heighten the materiality of both artists’ practices, but it serves neither well, consigning Balema to oblivion in the face of riotous color and diluting Jackson’s historical research by reducing it to formal play. It was a bummer getting off the sixth-floor elevator and seeing, as my first encounter with the show, Calvin Marcus’s anodyne canvases hung on the large wall in front of me, especially when, turning the corner, one can find some of the real treasures of the exhibition—sophisticated assemblage-based sculptures by the Puerto Rican artist Daniel Lind-Ramos that align the territory’s past history of colonialist occupation and the looming, post–Hurricane Maria threat of gentrification. On the floor below, a room that includes three of Simone Leigh’s monumental ceramic forms, Heji Shin’s photographs of infants at the moment of their birth, Janiva Ellis’s mural-sized, intensely colored landscape painting populated by cartoonish, distressed figures, and Keegan Monaghan’s large, crusty oil paintings of small, everyday details (a lock on a door, a wooden fence, a push-button telephone) seems to lack any real organizing principle. It also manages a feat I would have thought impossible—making Leigh’s sculptures look insubstantial.

Whitney Biennial 2019, installation view. Photo: 4Columns. Pictured (foreground, clockwise from left): Simone Leigh, #8 Village Series, 2019; Corrugated Lady, 2018; and Stick, 2019.

There are also wins: Nicole Eisenman’s Procession, a grouping of figurative sculptures dating from 2018–19, at least one of whom periodically emits massive clouds of flatulence, effectively transforms one of the museum’s outdoor terraces into a seriously odd sculpture garden. Brendan Fernandes’s installation The Master and Form (2018/19), consisting of a complex metal scaffold and various ropes and wooden supports attached to walls and placed on the floor of a large, windowed gallery on the fifth floor, commands its space beautifully, especially when animated by the ballet dancers who stretch and move in the room during scheduled performances.

Whitney Biennial 2019, installation view. Photo: 4Columns. Pictured: Nicole Eisenman, Procession, 2019.

On the eve of the opening of the show, Leigh—an artist representing an older generation in this emphatically young show, and one who has been key in forming creative networks among many of the younger participants via her role in establishing the group “Black Women Artists for Black Lives Matter”—posted a 1949 Fritz Henle photograph on Instagram. Titled Night in the Museum of Modern Art, New York, it depicts a black cleaning woman pausing momentarily with her broom to gaze at the sculptures of nude women around her. Leigh wrote, “Nothing distracts me from the importance of this moment” of contemplating an exhibition in which “the majority of artists are people of color and half are women.” It is, frankly, undeniable that the mere existence of this biennial at this institution feels radical. But the pressing question is: What kind of institution have these artists been admitted to, in the end?

Since December, the Whitney has been the target of protests for its affiliation with Warren Kanders, who serves as vice chair of its board of trustees. Kanders is the owner of Safariland, a company that profits from the sales of tear gas and ammunition to repressive governments around the world, including our own. One artist—Michael Rakowitz—refused to participate in the exhibition, while two others, Forensic Architecture and Pat Phillips, directly address Safariland, and by extension Kanders, in their contributions. A number of actions and interventions by other exhibiting artists are also planned. The dissonance of seeing vital and urgent work by so many artists of color in a museum that directly benefits from the teargassing of people of color is real, but it seems to me that it is a contradiction and crisis that we cannot expect artists alone to solve. As I walked through the show, I kept thinking of that brilliant headline in The Onion announcing Barack Obama’s election: “Black Man Given Nation’s Worst Job.” The moment is historic, no doubt, but what a broken system to be entering.

Aruna D’Souza is a writer based in Western Massachusetts. Her book, Whitewalling: Art, Race, and Protest in 3 Acts, was published by Badlands Unlimited in May 2018. She is editor of the forthcoming Lorraine O’Grady: Writing in Space, 1973–2019 (Duke University Press, 2019), and is a member of the advisory board of 4Columns.